Attacks on Trump must sound warning bells in Australia

Lone gunmen like the Trump assassins don’t emerge in a vacuum. The unholy alliance between hardline Muslims and leftists needs to be checked for the sake of the nation.

The US has a long history of political violence from which repeated themes emerge.

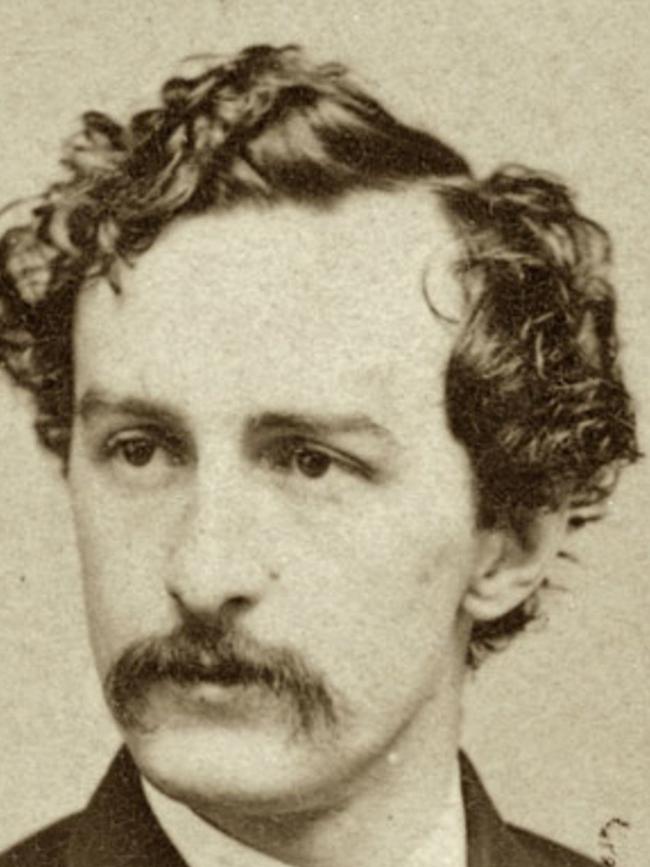

Next year, on April 14, will be the 160th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination at the hand of John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theatre in Washington DC.

Booth was a prominent actor and an open supporter of the Confederacy and slavery. According to Ronald White’s peerless biography of Lincoln, Booth held the president “in disdain as a man of low culture and coarse jokes”.

In the heated political climate of the civil war, Booth had earlier conspired with Confederate intelligence agents to kidnap Lincoln. He attended the president’s second inauguration speech in March 1865, saying “that was the last speech he will ever make”.

The president was more relaxed than his advisers about security. In 1862, travelling without a protective team, Lincoln dodged a bullet while riding his horse, Old Abe. Fleeing the scene, the president quipped: “I tell you there is no time on record equal to that made by the two Old Abes on that occasion.”

On the morning of the assassination, Booth learned of Lincoln’s short-notice plan to go to a play that evening. Lincoln attended giving the night off to a White House Guard.

There are different stories about whether a second guard was drinking at the theatre bar, or sitting watching the play rather than guarding the entrance to Lincoln’s stall.

Lincoln was shot in the head at very close range. Booth shouted “Sic semper tyrannis” (“Thus ever to tyrants”). Then followed the largest manhunt in US history to that point. Booth was killed by a Union soldier on April 26.

Trump is no Lincoln and his two failed assassins do not have the public prominence of Booth, but the parallels between America of the 1860s and today are interesting. The civil war had sharply divided Americans; people were armed, angry and uncertain over the country’s future direction.

Lincoln had overwhelmingly just won a second term on the back of long-delayed and very bloody Union military victories. In today’s political language, some might call him a divisive political figure. His Democratic opponent in the election campaigned on the charge that Lincoln would split the republic, destroying the United States.

Today Booth would be termed a fixated individual, politically obsessed, moving in a world of like-minded individuals with grand conspiracies, eager to change the direction of national politics.

The final ingredient is that Booth got lucky. Lincoln took a rare night off, went to the assassin’s theatre. Security was lax.

In 2024, Americans are divided, armed, angry and uncertain about their future. The left and right of American politics don’t hold back from accusing their opponents of dire plans to destroy the republic.

Up until now Trump has been more relaxed about his personal security than a man of his political prominence should be. After an AR-15 round took a notch out of his ear, Trump should have taken more caution about his public appearances.

Even less understandable is that it has taken two assassination attempts for Joe Biden to direct that more security is given to the presidential candidates.

No one has ever accused Trump of modelling Lincoln’s call of “with malice towards none; with charity for all”. With the former president’s celebrity, the failure of his personal security team at the Butler Farm Showgrounds in July is astonishing.

Astonishing but not surprising. The Secret Service is equipped to provide a thin protection and reaction capability around the president. Beyond a few hundred meters, local police provide security. We know that the capabilities of America’s 17,985 separate police forces vary enormously.

After gunman Ryan Routh was fired at and fled from his shooting position at Trump International Golf Club in West Palm Beach, Florida, the media was briefed that a Secret Service agent was moving one golf hole in advance of Trump and his party.

That’s about the full extent of the protective bubble, but a modern sniper weapon has a much greater range than the distance between two holes on any golf course.

The Russian SKS semi-automatic rifle Routh carried had a more limited range of 400m, but as we saw in the Butler Farm Showgrounds shooting even a relatively inexperienced shooter can hit a target with a modern weapon.

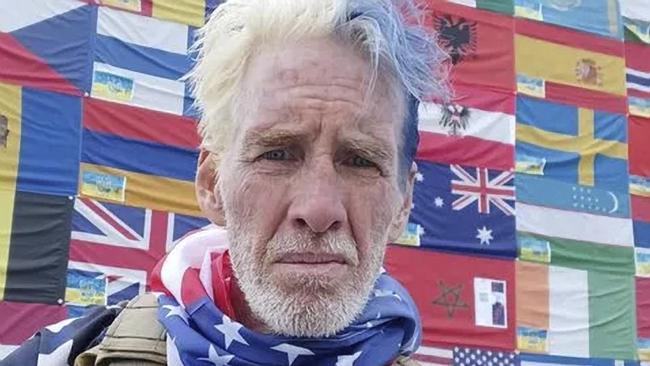

Beyond immediate protection issues there is usually intelligence agency and law enforcement knowledge of fixated individuals. Routh was certainly “known to authorities”. He had been convicted of possessing a “binary explosive with a 10-inch detonation and a blasting cap” – a bomb – after a stand-off with police in 2002.

Routh had self-published a book on the Ukraine war in which he claimed that readers were “free to assassinate Trump”, whom he called a buffoon. He left a substantial trail of social media activity. Like Booth 159 years earlier – and other assassins in later years – Routh was not hiding. He was in plain sight of authorities.

Yet no Western democracy is in a position to “round up the usual suspects”, to quote from the movie Casablanca, nor would most people want intelligence officers and police to have such sweeping powers.

This presents a huge challenge for internal security agencies. ASIO head Mike Burgess identified the catch-all phrase “politically motivated violence” to describe a much broader wave of radicalisation.

More people are more angry, more willing to believe and to create inflammatory propaganda, and are sparked more easily into acts of violence. People in domestic security jobs refer to a “zero to one hundred” phenomena where impatience with, say, a bank teller turns into a physical assault in seconds.

Add to that an overlay of political motivation or Islamist extremism and/or rapidly expanding progressive left extremism and the potential for violence, including against elected leaders, is becoming more acute.

In the US we will likely see a major security operation expand the protective bubbles around Trump and Kamala Harris from now up to the January 2025 inauguration.

It will be an easy enough matter to lock down Trump’s Florida golf course if that is deemed a national security interest. Candidate visits to coffee and donut shops will happen inside a protective perimeter of several city blocks.

Beyond the election, though, it is impossible to provide anything approaching iron-clad security for political leaders. There will be moments – like Ronald Reagan getting into his limo, or Shinzo Abe standing to give a stump speech – where the terrible stars will align, as they did for John Wilkes Booth in 1865.

What are the lessons for Australia? For 10 months I have been writing in these pages that our government is stupidly tolerating the rise of left progressive extremism under the guise of a Hamas cover-story, the pro-Palestinian movement.

There are two wings to this movement, neither of which the Albanese and state Labor governments have had the courage to properly handle.

One wing is Sunni-Islamist extremism, which in Australia since Al-Qa’ida’s September 11, 2001, attacks, has tolerated terrorism, provided funding, ideological support and several hundred fighters for Islamic State in Iraq and Syria.

The second element is “progressive” hard-left extremism with Marxist-Leninist roots and a grab-bag of ideological causes ranging from environmentalism, anti-US, anti-colonial and anti-Australian self-loathing.

The two groups unite with a common hatred of Jews and Israel.

The Albanese government will not crack down on these groups because they come from electoral bases that Labor needs to win re-election in 2025.

This is a shared problem for the US Democrats, the UK Labor Party and other centre-left political parties: their political bases are rapidly moving further left.

At the ends of that spectrum their support bases meld with extremists who have increasingly anti-democratic ideology.

One test of that is to watch the Australian Greens. Always to the left of Labor, the Greens are building a perilously close alignment to extremist groups. Bob Brown’s Greens of the 1990s is politically where mainstream Labor resides today. Adam Bandt’s Greens promotes a radicalism well beyond any concept of mainstream democratic politics.

Political extremism doesn’t have to tip into violence, but it can. Where it does, lone gunmen or lone wolves like a John Wilkes Booth or a Ryan Routh never operate in isolation. They emerge from a political context and engage with a likeminded community helping their radicalisation.

In Australia, the violence we have seen since October 9 last year is getting worse. Twenty-four police were injured in rioting outside the Melbourne Land Forces Exhibition last week.

It is a measure of how dulled our national political reactions have become that this violence doesn’t spark a shocked counter-reaction. Unchecked, the violence will increase. Hardline protesters will push the boundaries because their ideology drives them to that point.

There has been a rise of right-wing extremism in the form of a tiny neo-Nazi movement mostly in Victoria. This pathetic handful of black-shirts is endlessly discussed. In reality they are far out-shadowed by the rise of left-wing extremism, spurred on by its alliance with Islamist extremism.

God forbid, if there is an assassination attempt on an Australian politician we will look back at 2023-24 as the time when our leaders allowed extremism to incubate and grow more violent on our streets in the name of progressive left ideology.

The American experience shows that assassins occasionally get lucky well beyond their skills and capabilities. When that happens, intelligence and police services look flat-footed, rather like the current response to the march of left extremism in Australia.

Peter Jennings is a former deputy secretary for strategy in the Defence Department and a previous head of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. He is now director of the think tank Strategic Analysis Australia.

The assassination attempts on former president Donald Trump point to continuity rather than a shockingly unexpected turn in American politics.