Asia fears major fallout from another Trump US election victory

Asian governments are weighing the costs of a second Trump term with those of a Biden government, as pressure mounts to pick a side.

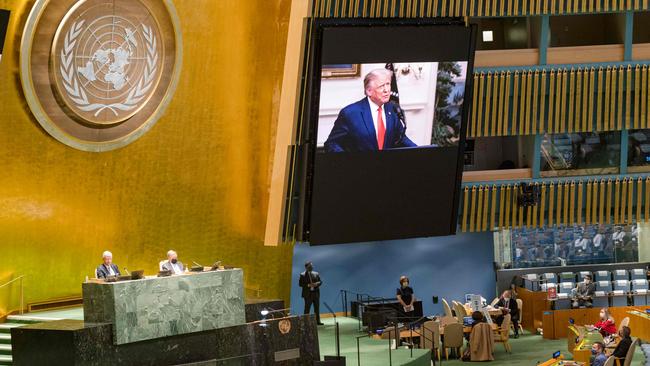

In the virtual amphitheatre of the UN General Assembly recently, the leaders of two of Southeast Asia’s largest economies outlined the growing alarm in Asian capitals at the possibility of spiralling US-China hostility leading to war.

“Given the size and military might of the contenders, we can only imagine and be aghast at the terrible toll on human life and property that shall be inflicted if the word war deteriorates into a real war of nuclear weapons and missiles,” The Philippines’ President Rodrigo Duterte warned.

Echoing those sentiments, Indonesian President Joko Widodo appealed for an end to the growing geopolitical rivalries that were threatening to destroy global stability and peace.

“War will benefit no one. There is no point of celebrating victory among ruins,” he said.

As the US readies for the presidential election on November 3, Asian nations are weighing the potential costs of a second-term Trump administration against those of a government led by Democratic challenger Joe Biden.

With the risk of conflict between the US and China more palpable today under the presidencies of Donald Trump and Xi Jinping than it has been in decades, one might assume Asia is looking to the US election for relief from the escalating face-off.

Yet with both presidential candidates pledging tough-on-China policies, Asian governments understand the US-China rivalry will not go away with a new man in the White House.

There is a growing realisation that while a Biden administration might calm the waters, its determination to work more closely with allies and partners could ratchet up pressure on Southeast Asian states to pick a side.

Malcolm Cook, a visiting senior fellow at Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, says where Asian states fall on the Trump vs Biden race is a harder read than those of Western Europe, “where you could make the argument that most would prefer a Biden administration”.

“If China had not been so aggressive during the Trump administration’s first term I don’t think there would be as much support for a second Trump term among Asian capitals,” he tells Inquirer.

He says countries that face the greatest territorial aggression from China are most likely to support the US incumbent.

“I would think Japan, India and Taiwan (all of which are grappling with escalating Chinese territorial aggression) would prefer Trump and I know people from the (former) Abe administration who are hoping for a Trump victory,” Cook says.

Likewise Indo-Pacific countries that border China and see it as a major threat are likelier to have welcomed Trump’s first-term foreign policy.

“My bet is Vietnam also likes the Trump administration’s stronger stance on China though would be worried they could be targeted for their massive trade surplus,” Cook says.

Few Asian leaders enjoy the unpredictability of the Trump administration and many fear a White House over-reaction under Trump could lead to war in their back yard. A recent push by US Defence Secretary Mark Esper to find a home in Asia for US intermediate-range missiles also is worrying its allies.

Conversely, there are concerns that a second-term Trump administration could make a deal with China that would leave East Asian nations out in the cold, while Trump’s decision to skip successive Association of Southeast Asian Nations-US meetings and other ASEAN-led discussions has put noses out of joint.

A January survey of Southeast Asian government, business and media elites by the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute found 60 per cent of respondents believed the US would be a better strategic partner if there were a change of leadership in November.

Eight months later the regional consensus appears to be that the threat of miscalculation or a shot fired in anger is more likely to occur under Trump than under Biden, who many believe would have a “calming” effect on the region and be less “China bashing” — as one Indonesian policy maker said recently.

Yet the paradox of the Trump presidency’s failure to engage in many of the usual ASEAN confabs is that, even as it has annoyed its 10 Southeast Asian member states, its unilateralism also has given them a free pass.

While the US administration has beefed up several security agreements across the region — and in recent months explicitly supported Southeast Asian claimants The Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, Taiwan and Brunei in their dispute with China over occupied islands in the South China Sea — it largely has gone it alone in its escalating dispute with Beijing, asking little of its security allies and partners.

By contrast, Biden has signalled his intention to involve “like-minded” countries in the region in addressing concerns over China, leaving the door open to making greater demands of US security partners and allies, including Singapore, Japan, The Philippines and Thailand.

That would not sit well with today’s more aggressive China, which Cook predicts would “likely react punitively to any signs that such American demands are being met”.

“A Biden presidency requesting partners for freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea in defence of navigation and overflight rights would make a few hearts skip in the halls of power of those nominated like-minded states,” he wrote in a recent Lowy Institute paper.

“In some sense, Southeast Asia has benefited from the Trump administration because there hasn’t been much real pressure from the White House on those states to actively side with the US against China,” says Cook.

Southeast Asian nations are desperate to avoid having to make a choice between the US, the security provider that has underwritten Asian stability and prosperity for decades, and China, now their dominant trading partner.

Singaporean President Lee Hsien Loong summarised the dilemma in July, writing in Foreign Affairs magazine that the “troubled US-Chinese relationship raises profound questions about Asia’s future and the shape of the emerging international order”.

“Southeast Asian countries, including Singapore, are especially concerned, as they live at the intersection of the interests of various major powers and must avoid being caught in the middle or forced into invidious choices,” he wrote.

“Confrontation between the two powers is unlikely to end as the Cold War did, in one country’s peaceful collapse.”

National University of Singapore associate professor of political science Ja-Ian Chong says ASEAN states have largely recovered from the initial shock of the Trump presidency, even if the relationship is not as easy as it has been with previous US presidents.

But the desire for a US-China rapprochement probably is stronger in Singapore, which depends on both economies, than in Vietnam, which faces greater territorial aggression from China and thus would prefer a stronger US position.

“Because of their very tense relationships with China, Taiwan, Japan and India would probably prefer an administration willing to take a clear stance against China and so far Trump people have shown their willingness to do this,” he tells Inquirer.

While Biden also has come out strongly against China, Chong says there are “residual concerns” that he will recruit figures who served in the Obama government.

ASEAN states have not forgotten Barack Obama’s largely failed Asia pivot or that it was under the Obama administration, in which Biden served as vice-president, that China was able to build up and militarise seven disputed islands in the South China Sea to support its controversial claim to 90 per cent of the strategic waters.

Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy associate professor of practice James Crabtree says no matter who wins next month, there almost certainly will be a more serious shift of military resources away from the Middle East and into the Indo-Pacific region.

“The reassuring thing for those in Asia who want the US to be engaged economically, diplomatically and militarily is it looks like the US is finally making that shift,” he says.

Still, he adds, Biden has a credibility problem in Asia, notwithstanding the likelihood of his administration bringing “calmer waters” to a region churning with territorial aggression.

“Obama-era advisers would admit they took their eye off the ball and did very little to impose costs on China in the early stages of the island-building process”, says Crabtree, though people are also “rather too sanguine about the dangers of a Trump second term”.

“I think it comes down to how anxious you are about China, and what I hear is countries most concerned about China are most relaxed about Trump.

“If you’re concerned about stability in the region you want to keep the US engaged. Biden promises more multilateral engagement and that’s a positive, but then there’s the negative which is that a number of ASEAN countries did not like the Obama-era finger-wagging, human-rights, democratisation talk and, in a sense, are reasonably comfortable with the way the US has behaved over the last four years.”

The Democratic Party’s commitment to act on human rights violations certainly could pose challenges for India, given Biden’s criticism over its crackdown in Kashmir and the citizenship amendment act that prioritises Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi and Christian migrants from Muslim-majority Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan.

Similarly Myanmar, facing accusations of genocide over its treatment of its Rohingya Muslim population, and The Philippines, where the Duterte administration’s murderous war on drugs continues, also might have to reckon with greater US scrutiny.

“I have heard a couple of Southeast Asian diplomats worry that if Susan Rice becomes secretary of state (under Biden) the human rights agenda would gain a very strong proponent given her time in the UN,” says Cook. On trade, too, the issue is not clear cut. Trump’s decision to pull out of the Obama-conceived, 11-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement — a deal that excluded China and was to be a centrepiece of US economic engagement in Asia — was a blow.

Many ASEAN states also have been on the receiving end of Trump tirades over trade disparity with the US.

Lee recently told US think tank the Atlantic Council that one of the things he most hoped for from the next US administration was that the country would “find a way to come back” to the TPP.

That is unlikely, regardless of who wins next month, given Biden’s election platform talks down the possibility of new free trade deals in the near future.

Both candidates are expected to work towards reducing US reliance on Chinese supply chains, a move ASEAN states hope will bring foreign investment from China-based US firms and manufacturers looking to relocate.

Senior Indonesian foreign ministry officials talked up that possibility in a recent online discussion.

Of all the ASEAN nations, Indonesia was perhaps fondest of Obama given his links to the capital Jakarta, where he attended school as a boy.

Trump also drove an early wedge into the bilateral relationship with Indonesia — a staunch defender of the Palestinians — through his decision to move the US embassy in Israel to Jerusalem.

Yet Indonesian foreign ministry officials say they see potential for foreign investment opportunities no matter which side occupies the White House.

Under Trump, “there might be relocation of foreign companies, American companies, from China to Indonesia”, said Zelda Kartika, the ministry’s director for North and Central American affairs in the discussion.

Similar economic benefits could flow from a Biden presidency, though “Biden will also speak out on non-conventional security issues; environment, democracy, immigration and also — something the Indonesian government must watch out for — human rights issues”.

Either way, she adds, “On the relationship with China, we must note that this is a bipartisan issue.

“The tension with China will continue.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout