As NT crocodiles grow bigger and bolder, talk of culling divides

Crocodiles, teeth and tourists don’t provide ideal optics for the NT but as the Territory’s crocodiles grow bigger and bolder, experts argue culling these robust predators won’t keep people safe.

On a mid-July afternoon, as school holiday crowds peaked at Wangi Falls, 130km from Darwin, 80 swimmers sped towards land as the cry of “Croc!” cut across emerald waters. A 67-year-old man had been attacked by a 2m saltie in Litchfield National Park, which receives 300,000 visitors each year.

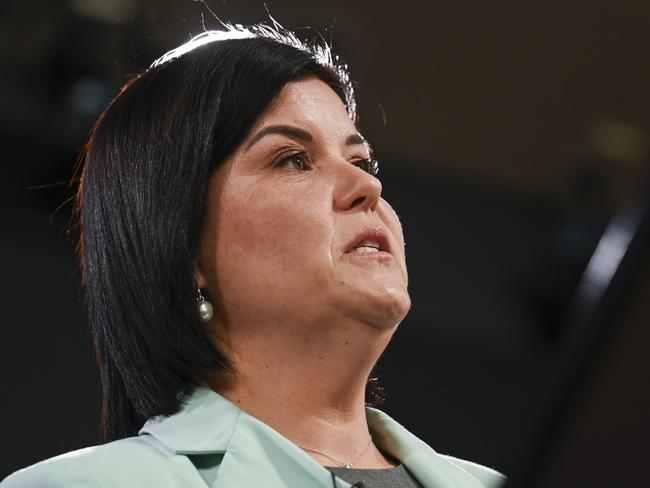

“It’s time to consider: do we need to go back to culling?” NT Chief Minister Natasha Fyles asked the next day, announcing plans to reopen the conversation with federal counterparts because of a “significant increase” in local croc numbers – up from 3000 in 1970 to an estimated 100,000 this year.

Crocodiles, teeth and tourists don’t provide ideal optics for the Territory and its $3bn tourism industry. Yet, according to experts, culling won’t stem human-crocodile encounters or keep people safe. Besides, targeted culls are already in place – they’re just not labelled as such.

Tens of thousands of crocodile eggs are taken from the wild each year and since January 179 crocodiles have been removed from government-managed waterways in the Top End, most from Darwin Harbour. Scores more crocs are trapped and killed on private stations and Indigenous homelands.

Still, they turn up in unusual places. Last year, a 2.5m croc was found in a caravan park at Dundee Beach, while another was taken from a backyard pool in Palmerston, a satellite city to Darwin.

For Kristen Hay, director of wildlife operations for NT Parks and Wildlife, the capture of a 4.5m crocodile in June at Elizabeth River boat ramp, 25km from the Darwin CBD, was striking.

“It’s concerning because for that croc to be there and not be reported, it’s gone past 10 traps,” she says. Some crocs won’t enter traps at all, she says: a reminder that reptiles enter Darwin Harbour and swimming is always risky.

“We can’t stop crocodiles coming in there. This particular croc had three turtle heads and a dog collar found in its stomach. The dog was taken from much further up the river. (That croc) went all over the place.”

Big river crocs, with full stomachs, are symbolic of the predator’s robust rebound in the years since protection began in the early 1970s. Before this, crocodiles were hunted for skins almost to the point of extinction.

In today’s ecological setting, thriving native species are hardly the norm, particularly in northern Australia where nine listed animals – including nabarleks (rock wallabies), phascogales and hopping mice – are at high risk of extinction in the next two decades.

While species such as these can fall victim to introduced pests such as cane toads, crocs have no such vulnerability. They’re thought to have encountered a similar toad in Asia along their evolutionary journey, triggering an immunity to cane toad poison. It also helps that crocodiles eat pests, including buffalo and feral pigs.

Says naturalist David McMahon, chief tour guide with Venture North Safaris: “There are potentially more crocs than there should be because of invasive species. There’s more food now than there was in the 1970s (when crocs ate mostly fish and crabs). There’s less buffalo but more pigs, and pigs are a real favourite food of crocodiles.”

Funding for feral pig and buffalo reduction therefore could push croc numbers down, he suggests, as these populations self-regulate according to the amount of food available. When there’s less of it, they start killing each other.

Similar findings arose from a coronial inquest into the 2014 death of 62-year-old Bill Scott in Kakadu National Park, where flood plains draw feral animals. That year the Top End fishing community was shocked when a croc grabbed Scott from his boat.

The fatality sparked calls for croc culling and online sites such as Gumtree were flooded with roof-topper dinghies for sale. A steady flow of deaths followed across the next four years or so – about one or two annually. Deaths have dropped off significantly since.

It’s a different story a hop away in East Timor, where “so many people get eaten by crocs, it’s not funny”, croc expert and Crocodylus Park owner Grahame Webb says, referring to the island nation’s average of one death a month. In Indonesia, things are far worse. There, the official 2022 count stands at 71 fatal attacks, though the true number likely rests at more than 100, due to under-reporting.

Wildlife biologist Brandon Sideleau, a Charles Darwin University PhD candidate studying croc attack patterns, says crocodile habitat destruction and over-reliance on the river system puts many Indonesians in danger: “There’s just a lot more poverty, a lot more people,” Sideleau says.

Rivers serve as a hub for bathing and finding fresh water. They’re also sites where prey depletion and mangrove habitat degradation occur because of palm oil, tin and sand mining activity. These factors push crocs to higher ground and into the path of humans.

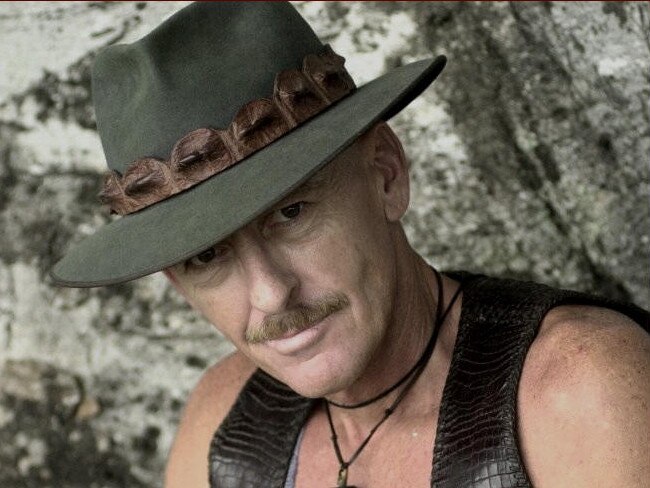

“They can move from gracefulness to ferocity like the flick of a switch,” says Darwin crocodile hunter and taxidermist Mick Pittman, who has spent four decades capturing and killing problem crocs, tanning hides with bark and making leather products and stuffed crocodile heads from animal remains.

Pittman learned his craft from renowned croc hunter “German Jack” Kiel after jumping on a croc’s back and wrestling it into submission during a trial boat trip with Kiel in the 1980s. The younger hunter quickly learnt to spot telltale bubbles on the water’s surface and to track the whereabouts of predators in the bush.

More recently, Pittman has hunted on behalf of station owners who, along with traditional owners, can use licensed contractors to remove crocs from their land.

“You catch the animal, secure the animal, you tie his jaws up, you pull him in, you dispatch him,” Pittman says of the process, noting that Australia has had about 250 registered croc attacks since white settlement. “There’s a lot of people who come here now and respect the animal and realise they’re going into the bush where there’s a creature that eats you,” he says. “And then you’ve got the hoo-has, the ‘look-at-me, look-at-mes’. And there’s been a lot more of them since social media’s been around.”

Just a month ago, locals from Babinda, 50km south of Cairns, lambasted three young women for taking and posting photos metres away from Clyde, a well-known 4m croc.

“It’s a real shame because people (taking selfies) can interfere with traps and all sorts of stuff,” Pittman says. “You might have a croc sitting under that trap. The perception of the croc has changed. There’s a lot of people saying there’s too many of them. But I try to educate them, and say, ‘Well, they’re back to where they were in pre-settlement times’.”

As the NT’s croc population matures, bigger animals emerge. Crocodiles’ biomass, their overall volume measured by weight, is growing at a far faster rate than the overall number of animals, a rise Hay describes as “marginal”. Density sits at 5.3 adult reptiles per kilometre, compared with 1.7 in Queensland and about four in the top of Western Australia. Yet density doesn’t affect attack rates.

The NT’s last crocodile-inflicted death occurred five years ago when a female Indigenous ranger was taken in waist-deep water at Arnhem Land. In Queensland, a fisherman died in 2021, and in WA a teenager died in a mangrove swamp in 2013 – the state’s only crocodile death in the preceding three decades.

Australia has the lowest attack rate of all countries with saltwater crocodile populations, Sideleau says. Here, alcohol and complacency pose bigger issues than poverty or river reliance do.

In 2009, Lynda Bennett’s 11-year-old granddaughter, Briony, was swimming with her sister and friends at the Black Jungle Conservation Reserve near Darwin’s rural area when she called out for help and sank underwater, seemingly entangled in vine but instead having encountered a crocodile.

“Briony was taken. We lost her,” Bennett says from her home in Queensland. “And I couldn’t understand in this day and age how something like this could happen.”

Bennett’s first reaction, which she describes as “kneejerk”, was to have “every single, solitary crocodile removed off the face of the earth. I would have been happy with that … I wanted to bring about the demise of these creatures.” But instead Bennett and her daughter Charlene O’Sullivan, Briony’s mother, sought to understand the attack.

The death sparked a coronial inquiry and a discussion of the urgent need to update swimming safety messaging. From there, the NT government’s Crocwise campaign started, Bennett says.

“That kind of throws a wobbly in it for some people: when they think that I’ve gone from a loss to an absolute understanding of crocodiles. I mean, they are the most magnificent of creatures.” O’Sullivan went on to buy a crocodile farm, while Bennett lends her voice to crocodile conservation.

Rather than creating safer waterways, culling has the opposite effect, Bennett argues. Removing big crocs can result in smaller, more aggressive crocs vying for newly vacated territory and their presence may heighten, rather than quell, waterway danger. Culling also creates a false sense of security and may exacerbate people’s sense of complacency.

“We don’t need a cull, we just need people to be aware they’re there,” Bennett says. “And if you can’t see them, they’re still there. So stay out of the water unless it’s a pool or a bathtub.

But the pool at my daughter’s place is a bit iffy anyway, as baby crocs wander in there – not from the farm but from the wild.”

In Bennett’s home state, calls to consider culling are louder than they are in the NT. The Katter Party wants Queensland’s croc population cut by 25 per cent.

The Nationals’ Barnaby Joyce also supports culling. Responding to journalist Andrew Bolt’s suggestion on Sky News that Fyles’s “cull question” was sparked by “revenge” for the non-fatal Wangi Falls incident, Joyce told Bolt he took the side of humans over that of creatures who were “brilliant at killing people”, especially when tourism suffered.

Though just how much croc attacks adversely affect tourism isn’t clear; among some visitors, demand to see crocs in the wild can remain strong, even immediately after an incident.

Queensland’s croc distribution is different from that in the NT. Animals in Queensland live along long stretches of coast that hug developed land as well as in river systems. The state lists crocs as a vulnerable species, unlike the NT where, as Webb says, crocs are “coming back like an express train”. These factors complicate the way a cull might work, plus its potential effects.

“There’s a lot of movement of crocodiles between Queensland and Papua New Guinea,” Sideleau says. “If you remove crocodiles from Queensland you’re going to have predators who just repopulate and some of those may be experienced man-eaters from PNG rather than crocodiles that are not experienced. Because in Australia when a crocodile eats somebody it’s removed.”

While this is mostly true, and it is policy among the NT’s managed crocodile zones to kill rather than relocate problem animals, some Indigenous communities see the animal as less of a threat and more of a cultural fixture.

In northeast Arnhem Land, for example, the Bawaka homeland has Nike, a crocodile named during a visit by Olympic sprinter Cathy Freeman in honour of her sponsor. Despite reportedly having eaten someone, Nike is considered an ancestor to local people, who want the croc protected.

“They know that if he’s around, it’s a danger they can see. He’s protecting that area from other large crocodiles being territorial,” McMahon says.

“That’s a very different idea. They actually feed this crocodile. It’s part of their family. It’s got a skin name. It’s got a culture.”

Jennifer Pinkerton is a Darwin-based environmental journalist.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout