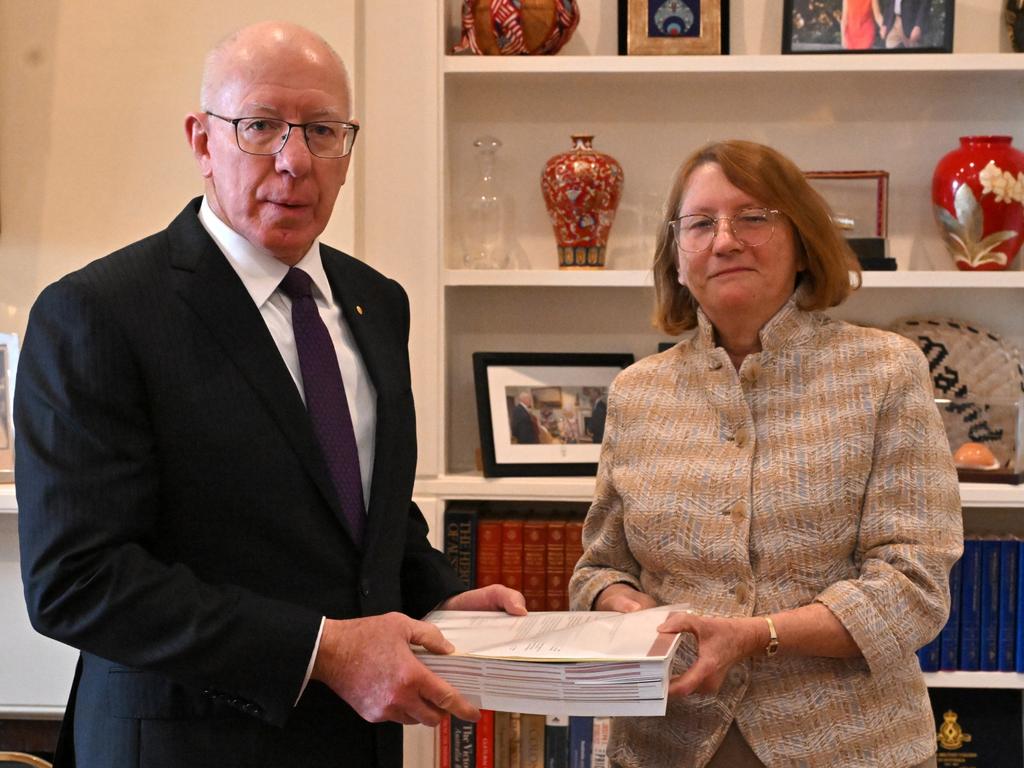

Argument of First Nations assimilation vs self-determination still rages

Today’s voice debate echoes an historic clash – assimilation vs self-determination – on the way forward for First Nations Australians.

Would a voice to parliament divide Australians or bring us together? Those irreconcilables have faced off many times since they first appeared more than 60 years ago in one of the most bitter and consequential debates in Australian intellectual and political history.

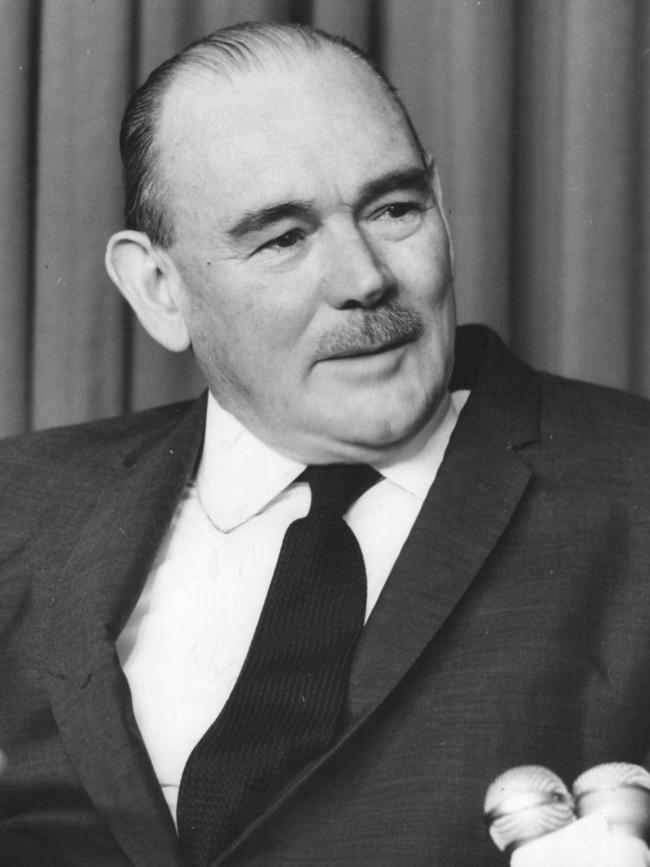

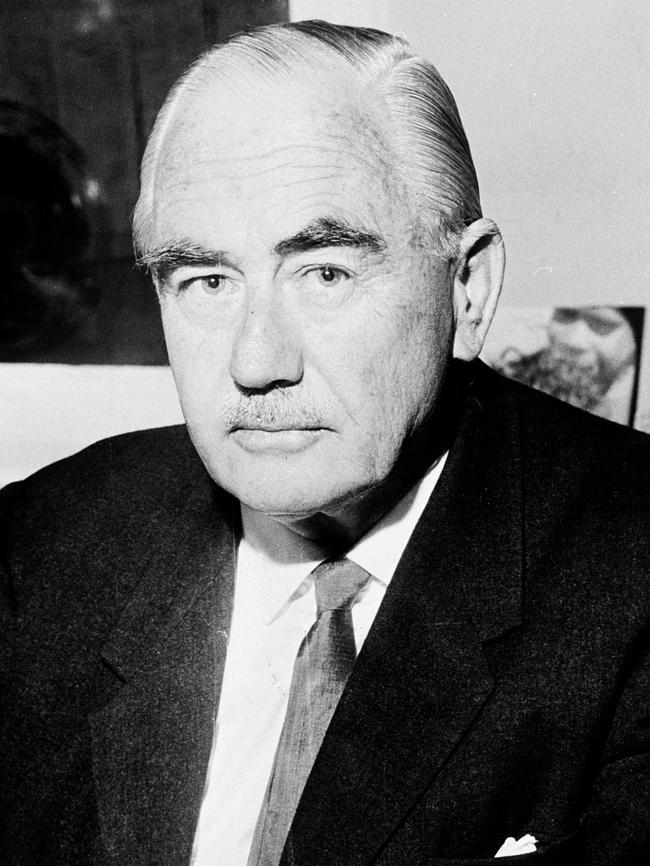

Paul Hasluck was appalled by the condition and treatment of Aboriginal people and so was Bill Stanner. They were in this and many other ways so alike as to be near-doppelgangers.

Both were born in 1905. Both were conservative by temperament, conviction and political affiliation. Both rose from humble circumstances via early careers in journalism. Both were intellectuals closely interested in politics; one became a major political figure, the other a great anthropologist and public intellectual. They disagreed on not much more than one thing: what was the way forward for the Aborigines? On that their disagreement was profound, even visceral.

For Hasluck the defining experience came in the US, first as a member of Bert Evatt’s team in the drafting of the UN charter in San Francisco, then in New York as Australia’s representative on the UN Security Council, at that time the epicentre of world politics.

Deep involvement in an institution formed in response to the horrors of fascism combined with first-hand experience of American racial strife to give Hasluck an abiding fear of racial division and to confirm a long-held conviction that equality was the only viable way forward as well as the only just one.

Back in Australia in the late 1940s Hasluck was soon in parliament and then minister for territories in successive Menzies governments. On constant guard against “racial feeling” from any quarter, including from Aboriginal people, he defined equality as the full assimilation of the despised and miserable Aboriginal population into the mainstream of Australian life. He was determined to make Aboriginal people Australian citizens, Australians like any other, no more, no less. This wasn’t an offer. Those ready for citizenship were granted admission forthwith; those not would be prepared for it by all available means.

Stanner reached his very different position from different experience. Beginning World War II as a newly minted anthropologist, he had spent extended periods among the Aboriginal people of the far northwest of the continent. He ended the war as Lt-Col Stanner (ret), reporting on the early stirrings of anti-colonialism from various outposts of empire to governments in London and Canberra. One of those outposts was Kenya. There Stanner watched the unfolding of one of colonialism’s great farces, the Kenyan groundnut scheme. An utter failure seen by colonial administrators as the fault of lazy Africans was understood by Stanner as an imperial fantasy that tribesman would willingly turn themselves into agricultural labourers.

Stanner returned to Australia (and Canberra) at much the same time as Hasluck, to take up an academic position at the infant Australian National University. Supposedly researching the Pacific and its people, Stanner was more interested in Aboriginal life and people, and increasingly dismayed by Hasluck’s assimilationism. It was, he decided, exactly what he’d seen in Kenya, a dispossessed people being patronised by dispossessors who wanted them to “unbe” who they then were.

It was a lonely and unpopular position, even among his fellow anthropologists, but if anything isolation increased his anger. Stanner’s attack on Hasluck’s policies was savage, effectively an attack on Hasluck himself as the self-appointed “Noble Friend of the Aborigines”, patronising, arrogant, with no interest in what Aboriginal people thought or wanted. In reply, Hasluck, riding high as a minister of the crown and on a rising wave of support for assimilation, declined to even mention Stanner by name, launching into a presumably unconscious parody of the Noble Friend.

“How many poor wretches have been dragged into the arena of social controversy and butchered to make a reformer’s triumph or a prize-winning newspaper story?” he asked rhetorically. How different was such moral vanity from the humility of government, that “sheltering, protecting, guiding, teaching and helping and eventually, as the final act of welfare, quietly withdrawing when the Aboriginal enters the community”.

The wave of support for equality by assimilation reached its peak in the celebrated referendum of 1967, when an astonishing nine out of 10 Australians voted for a Constitution that put the “Aboriginal race” on the same footing as everyone else.

In 1968, just a year after the referendum, Stanner delivered what are still regarded as the most eloquent and influential of the ABC’s long-running Boyer lectures, and one of the most important statements on relations between black and white Australians ever made.

The Boyers were, among other things, a warning: assimilation was well-intentioned but naive and ignorant, and so was white Australia. Aboriginal people were “coming back into history”; they would never agree to go back into the shadows to which they’d been consigned, nor should we want or ask them to. Theirs was an elaborate and enduring civilisation that we had assaulted from every direction. Our violence, diseases, diet and intoxicants had reduced their numbers by 90 per cent.

But they had survived and the survivors had no wish to “unbe” themselves. The least we could do was offer self-determination. If individuals or groups or all Aboriginal people opted to be assimilated into the wider Australian community then we should of course accept them, but that was their decision, not ours. If they wished to be recognised as a distinct people and treated accordingly, then we should accept and support them in that decision too.

Just as Hasluck had insisted that equality through assimilation was the only viable and just solution, so did Stanner insist on self-determination.

Most Aboriginal organisations were already there. They had led the referendum campaign because they wanted equality and its rights – much to be preferred over what they’d been getting for 170 years – but most also wanted recognition as Aboriginal Australians. A consensus based on assimilation was collapsing; the white political world was dividing.

Labor split from the Coalition, the Coalition split between the Country Party (now the Nationals) and the Liberals, and the liberal Liberals split from the conservatives – alignments still almost exactly as they were when formed more than a half-century ago.

No one has changed their minds. And this included Stanner and Hasluck. Not long before he died (in 1981) Stanner wrote that he wished he’d been more forthright. Not long before he died (in 1993) Hasluck wrote the last of his many books in defence of assimilation.

In the meantime, on one issue after another, on land rights, stolen children, compensation and reparations, a treaty, on memorials and national symbols and celebrations, and now on the voice, we have been over and over the same fundamental disagreement on the same fundamental grounds: will recognition of unique experience and standing of the Aboriginal people (and our unique relationship with it) bring us closer to reconciliation? Or will it keep us apart?

That recurring conflict, along with our determination to have the last say and to insist that we always know best, has delivered promises delayed or unkept, hopes dashed, concessions made then taken away, and cheese-paring, niggardly compromises.

Whether a voice to parliament would draw us towards reconciliation we may never know. But we can be sure that more of the same certainly won’t.

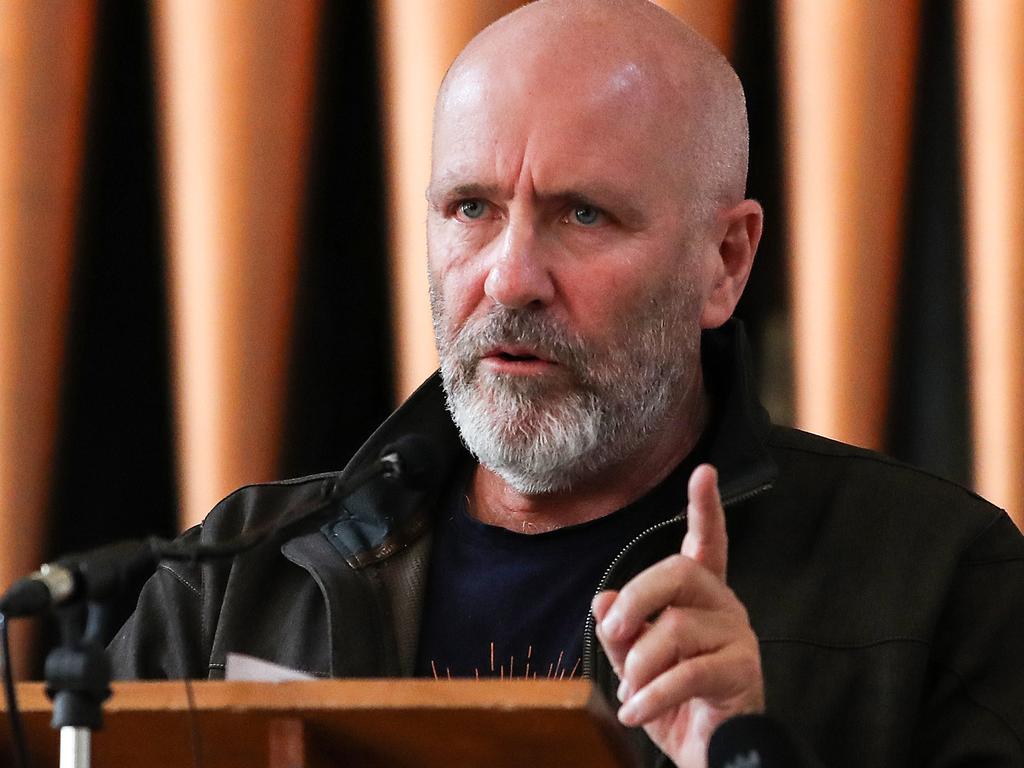

Dean Ashenden’s Telling Tennant’s Story: The Strange Career of the Great Australian Silence (Black Inc) was 2022 Australian Political Book of the Year.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout