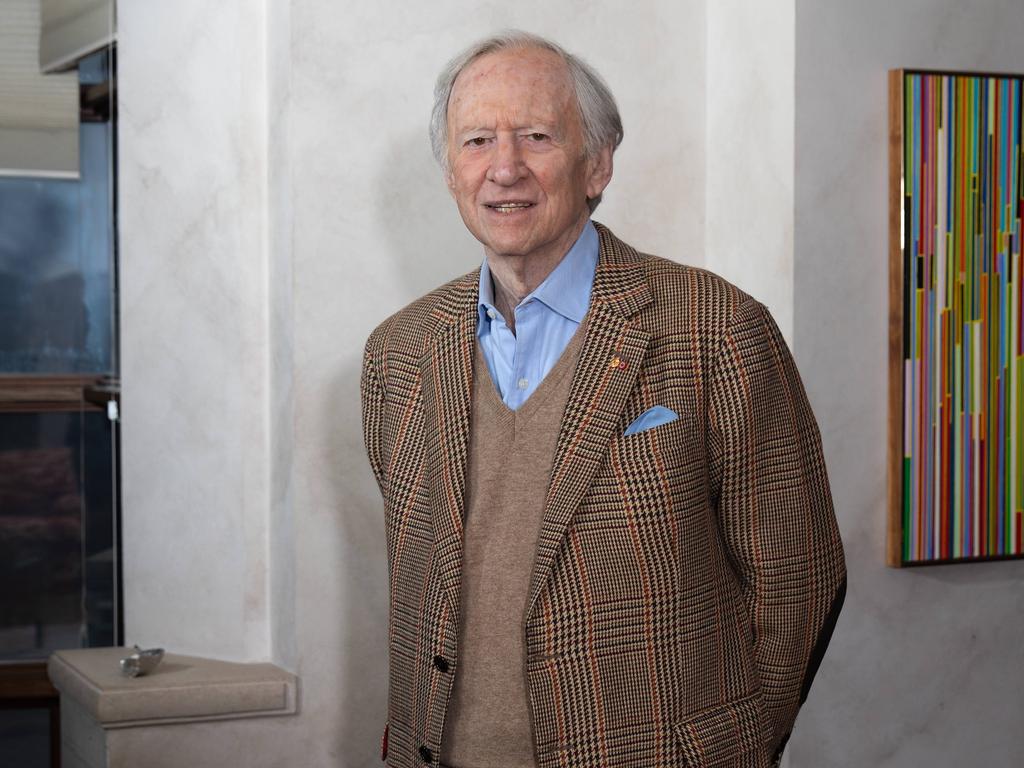

Andrew Peacock brought talent and personal style to the Liberal Party

Disappointed in his leadership ambitions at home, Peacock was an internationalist who served us on the world stage.

Having succeeded Sir Robert Menzies in 1966 in the seat of Kooyong, Peacock was forever stamped with the aura of being a future prime minister but his career can only be understood in the context of his prolonged rivalry with Malcolm Fraser and then with John Howard. While Peacock failed to achieve the highest office this disappointment rarely afflicted him, and he lived a rich and fulfilled life.

As a politician Peacock had appeal, style and presence; as a man he was engaging, generous and decent. For much of his career Peacock appeared ahead of his time, yet towards the end Australia seemed to have moved beyond the leadership he offered.

From its first sighting, Peacock’s star was prematurely hailed as a new sun: a Liberal Party member at 16, Liberal candidate at 22, president of the Young Liberals at 23, president of the Victorian division at 26, the successor to Menzies at 27 and a federal minister at 30. Not even this resume can capture the enthusiasm Peacock generated in his early years in politics nor the flamboyance he brought to a drab, grey parliament, a few notables excepted.

Peacock became a media favourite. He was a participator, keen to make new friends, a genuine Liberal but looking for change, fascinated by the latest trends in society and culture. He paid his way to visit southeast Asia, caught a bus to Paris at the height of the 1968 student riots and was drawn irresistibly to the dynamic of the US. At a time when Australia remained stubbornly provincial, Peacock grew as an internationalist.

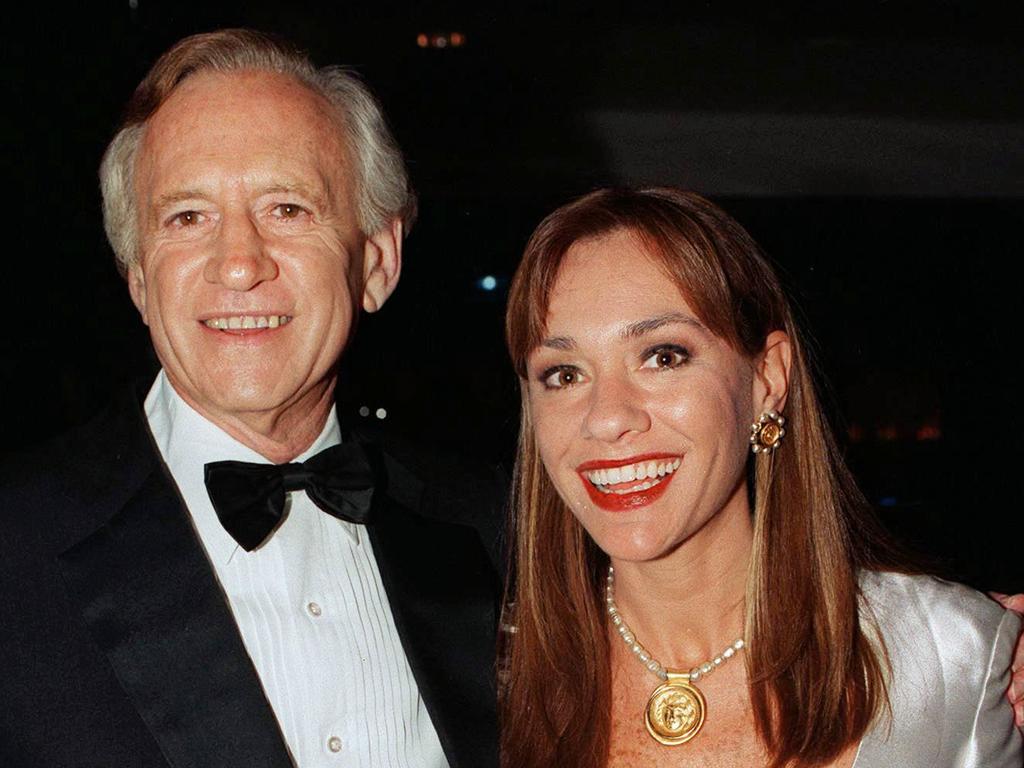

For many supporters, Peacock became the party’s best future hope as it struggled through the post-Menzies era under the leadership of Harold Holt, John Gorton and Billy McMahon. Born in Melbourne in 1939, Peacock died in Texas, aged 82, married to Penne Korth, his third wife, a successful American businesswoman, close friend of the Bush family and a prominent Republican.

Over the years Peacock developed an extraordinary range of high-profile contacts in the US on both sides of politics: he had strong connections with the Kennedy and Bush families, Cy Vance, Teddy Kennedy, Madeleine Albright and Henry Kissinger among others.

Of his generation he became the best-connected politician to influential figures in the US system and congress. He gave Australian governments insights into future trends, an example being his 1999 advice to then foreign minister Alexander Downer on the prospect of Texas governor George W Bush running for president, advice Downer promptly followed up.

In the end Peacock served twice as Liberal leader, initially in 1983-85 and again in 1989-90, facing Labor during the Hawke/Keating era when it was at its most formidable. While he had two chances at the prime ministership he was not blessed with luck contesting a popular Bob Hawke at the 1984 and 1990 elections.

His ministerial career began when appointed minister for the army under Gorton during an increasingly unpopular Vietnam War and facing a headstrong Malcolm Fraser as defence minister. Their personality and policy differences were factors leading to the 1971 crisis and Gorton’s replacement by McMahon. Peacock survived the transition and was soon appointed minister for external territories, where he turned a graveyard of bureaucratic reaction into a beacon of achievement.

In 1972 Peacock made a personal commitment to independence for Papua New Guinea and established a close rapport with its chief minister, Michael Somare. His dedication was intense as he spent countless hours travelling between Australia and Port Moresby. Foreign Minister Marise Payne said in her tribute to Peacock that his “lasting legacy” would be his commitment to PNG before and after independence.

The portfolio was ideal for the image Peacock was cultivating — as a politician of the future in a party burdened with too many old men. As the nation waited for Gough Whitlam’s victory, the political mood was leftwards and Peacock put an emphasis on liberalised censorship, lowering the voting age to 18 years, ending Australia’s status as a colonial power and removing any shred of racism from immigration entry.

Peacock married Susan Rossiter, daughter of a Victorian Liberal minister and they became a glamour couple. Susan waterskied off the Great Barrier Reef on the shoulders of Pierre Trudeau. They had three daughters. The media drew parallels with the Kennedys but the expectations rose too high. In 1970 Peacock offered to resign over Susan’s endorsement of Sheridan sheets for The Australian Women’s Weekly, a sensitivity that betrayed better judgment.

During the Whitlam government the Liberals underwent a critical leadership trauma with Fraser deposing the leader, Bill Snedden, in a brutal contest. By this stage the friction and rivalry between Fraser and Peacock had entered the soul of the party. The battle was not just about their ambition but the nature of the Liberal Party itself; Fraser the champion of the conservative wing and Peacock the progressive side.

Peacock served as foreign minister during 1975-80, the first two terms of the Fraser government. Despite their differences, their professionalism made for a competent but contrasting double act. It was not without its advantages — Fraser was grit and determination, Peacock charming and a master of soft power. Australia’s international standing was enhanced. But the showdown was destined to happen. In 1982 Peacock challenged Fraser for the prime ministership with his strongest supporter, Senator Reg Withers, declaring: “The colt from Kooyong has embarked on a journey for the jugular.” Peacock was soundly defeated, 54-27, and, in the process, Howard emerged as the party’s deputy leader, an omen of future trouble for Peacock.

After the 1983 election defeat Peacock became leader, Howard his deputy. This was a daunting job as the party struggled with its loss. Peacock displayed a skill and resilience that surprised many, holding the party together during the zenith of Hawke’s popularity and running an effective 1984 election campaign, a campaign he was never going to win.

The following year, however, Peacock’s lack of tactical skill was exposed when in a bizarre series of events he forced a showdown with Howard, failed to remove his deputy and, as a result, resigned the leadership. For the Liberals the story of the 1980s became the protracted Howard-Peacock rivalry, and it consumed the party.

In 1989, encouraged by a core group of backers, Peacock deposed Howard, returned to the leadership but succumbed again to Hawke at the 1990 election, the Labor leader’s fourth and last victory. These events offered deep insights into Peacock, who never pursued politics with the remorseless drive of Fraser or Howard nor shared their tenacity on policy.

Indeed, when the pro-Peacock rebels first spoke with him about a return to the leadership he was equivocal and, in the end, had to be pushed over the line by the organisers. Herein lay the great Peacock paradox — the man always feted to become prime minister actually lacked the overweening ambition and singular ruthlessness for the office. His friend and former chief of staff, John Ridley, said in his tribute that Peacock wasn’t sure he really wanted the job enough — an accurate assessment, not a condemnation. Peacock had passions outside politics, notably the horses.

Indeed, his personal life had been enhanced with his marriage to Margaret Ingram, who was well known and liked in political circles. Yet the trouble for Peacock in the 1990 campaign was his image as a popular yet jaded politician. Paul Keating, deploying one of the putdowns of the decade, put the question: “Can a souffle rise twice?”

Five days before the poll I published in The Australian a tough page one piece suggesting Peacock did not meet the national interest test for high office. Peacock was both dismayed and angry. The next day, after his speech at the National Press Club, Peacock sought me out on the floor where there was a nasty exchange between us filmed and shown that evening on the TV news.

During the late afternoon, however, he had rung me to offer a genuine apology for his behaviour. I thanked him but said he didn’t need to apologise: it was a damaging article at a critical time and I understood his anger. I saw this as a measure of Peacock’s decency. The rift between us soon faded and we enjoyed many fruitful discussions during and after his departure from parliament.

The 1993 re-election of Labor under Paul Keating was Peacock’s last outing. He recognised the tide of history. There was no point staying in politics merely to deny Howard’s return as leader. In 1994 Michael Kroger had asked Peacock if he would back Howard’s return and he replied: “Never.” But Peacock’s resignation later that year was an implicit admission that the party would decide its own destiny — and that was Howard, who won the 1996 election.

The Peacock-Howard story had a good ending. No longer rivals, they reconciled. Howard made an obvious but brilliant appointment — Peacock went to Washington as ambassador, and thrived. Australian politicians and journalists remained in his debt as they visited the US and absorbed his insights. After politics he served as Boeing Australia chair. In 2002 he married Penne Korth and they lived in Austin, Texas. Peacock never lost his fascination for US politics and tipped Donald Trump to win the 2016 election.

Peacock radiated a zest for life. He shone on the national stage and in public life. He aspired to make Australia a better place and a more outgoing and successful country in the world. His generosity touched many people and he learnt one of the most vital lessons in politics — to manage your successes with humility and your defeats with courage.

Andrew Sharp Peacock was a gifted son and diligent servant of the Liberal Party during his long 28 years in the national parliament — conspicuous for his natural political talent, his touch of personal magnetism and deep understanding of Australia’s role in the world.