Ancient Greek and Rome political debates show modern need for clear, critical thinking

A showcase for the enduring relevance of ancient Mediterranean political debates provides a refreshing example of the university environment at its best.

Our universities come in for a lot of criticism these days. Much of that criticism seems warranted. Spare a thought, however, for those scholars – who do indeed still exist – trying to pursue serious research and teaching in the midst of unprecedented technological innovation and relentless ideological campaigns directed against the very things that Western universities were founded to do and on which the reputations of the best of them still rest.

Those things are the liberal arts and the pure sciences. At the root of these disciplines are the fundamental sciences of thinking clearly and critically at all, rather than dogmatically or irrationally.

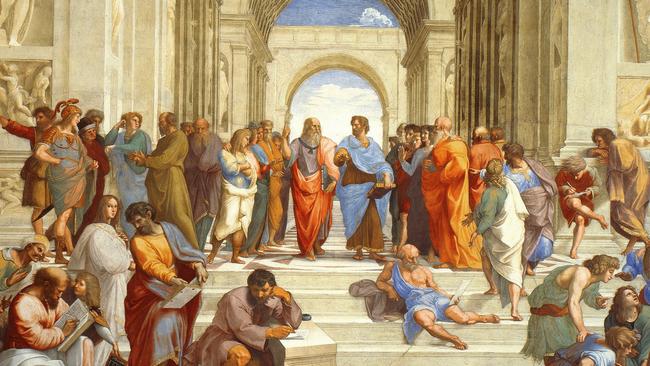

Alongside them and originating in the same classical works and schools – chiefly those of Plato and Aristotle – are the political and ethical sciences: what makes for sound governance and what is the good life?

Last month, by invitation, I participated in a conference at the University of Melbourne, under the title How Republics Die: Creeping Authoritarianism from the Ancient to the Modern World. In the broader context of what is happening at Western universities in our time, it was a breath of fresh air.

Funded by the Australian Research Council, it was organised by a friend of mine, Frederik Vervaet, Professor of Ancient History at the University of Melbourne. I was there simply to listen to the 21 papers presented and to ask questions of the speakers. What took place was a deeply serious discussion of the failure and fate of the ancient republics and the lessons we can learn as we confront the crisis of contemporary liberal democracies.

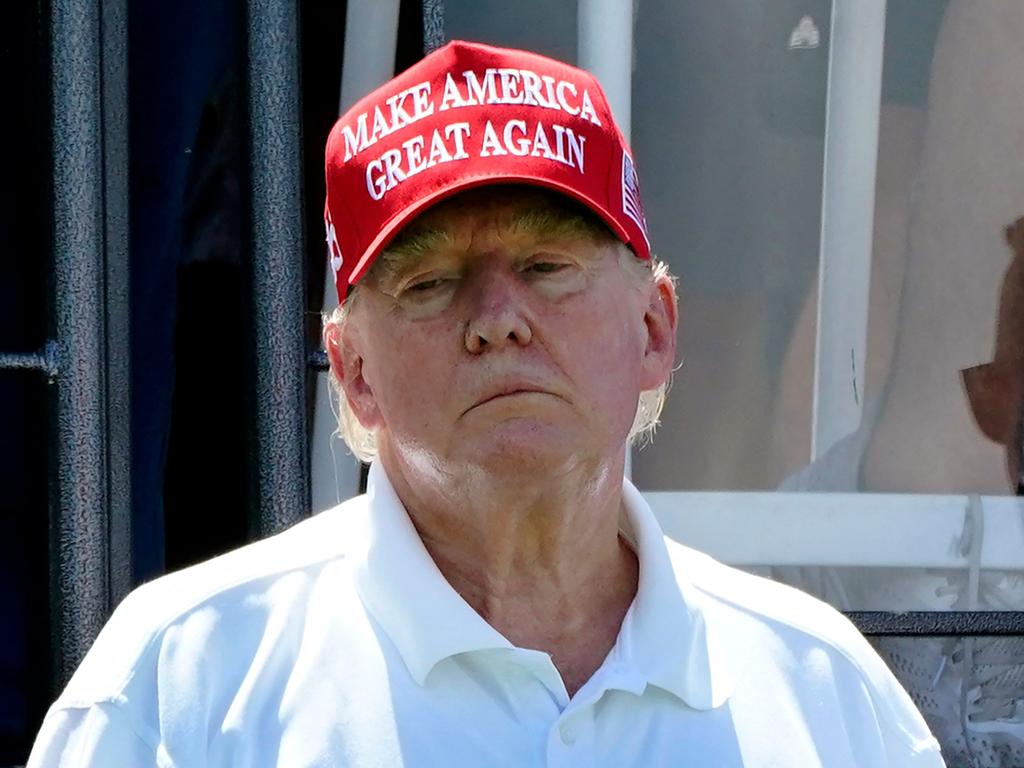

The common reference point throughout the conference was Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt’s 2018 book How Democracies Die. I had with me Charles Dunst’s 2023 book Defeating the Dictators: How Democracy Can Prevail in the Age of the Strongman. Both books are chiefly concerned with the polarisation of American politics and the danger of its democratic institutions foundering in the age of Trump.

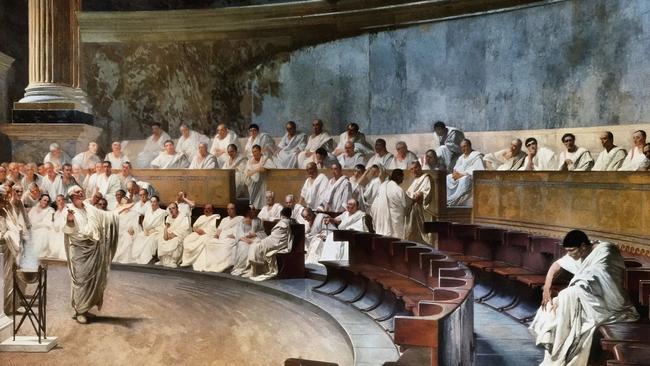

But the focus was on how and why the Roman republic, which had lasted for centuries, lapsed into dictatorship by the late 1st century BCE. As a generalist, I was fascinated by the detailed scholarship brought to bear on these questions by the presenters. Was it dry as dust pedantry? No. It was cutting-edge analysis of constitutional and political crises strikingly similar to those we face today, but viewed with the advantages of long hindsight and centuries of critical analysis.

We were discussing debates that had taken place more than 2000 years ago, concerning the rule of law, the nature of liberty, voting procedures, coups, political violence, the rotation of elective office versus monarchy, the nature of demagoguery, the enfranchisement and rights of “the people”, riots and proscriptions – and finding them all breathtakingly relevant to our 21st century concerns. This, surely, is the university environment at its best.

Worldwide and for millennia, human societies have gone through alternations of peace and war, civil order and disorder, tyranny and wise governance. But there is nothing else anywhere in the world from 2000 years ago or until very recently, that can compare with the history and recorded debates about law, liberty and republican government that we have inherited from classical Greece and Rome. Those debates – and much else besides that originated in the classical Mediterranean world – are the bedrock of modern democratic politics, not in the West alone but worldwide.

When the American Founding Fathers, in the late 18th century, set about conceiving and founding a republic, they had those debates very much in mind: the political and historical reflections of Aristotle and Polybius, Cicero and Tacitus. All this was on the table at the conference, and it was bracing to participate in the fine-grained re-examination of issues that have been debated ever since the downfall of the Roman republic and the rise of the so-called Principate – the one-man rule of Augustus.

My old Roman historiography teacher, Ronald Ridley, gave a talk about Augustus and his “template for dictatorship”. But the speakers were not all Australian and the Australians were not all based at the University of Melbourne. They came from England, France, Spain, Russia, New Zealand and the US. Yet the exchanges were invariably polite and reasoned, the disagreements far more to do with evidence, translation and logic than personal vanity or ideological dogmatism.

I could almost have been at a conference on physics convened by, say, Robert Oppenheimer.

This was so refreshing, against the background of endless emotive and partisan carry-on on social media platforms and our depleted and degraded mainstream media. It was like going from a jeering, heckling pub argument to a gathering of learned rabbis discussing the complexities of the Torah.

Of course, most of us would find rabbinical conversations about the Torah impenetrable and soporific – unless we were steeped in the Torah ourselves and serious about the interpretation of the Hebrew Bible. This conference on creeping authoritarianism was the political science and history equivalent of such conversations. And who among us is not concerned, right now, with politics and human history?

I was among specialists and finding the minutiae of their discourse about ancient debates immensely interesting. I had earnest questions for every speaker, about both the logic of their arguments and the implications for our time of those arguments. And in every case I got serious and articulate responses. Imagine, for a moment, a parliament that worked like this – or a social media platform.

The conference organiser, Frederick Vervaet, with Christopher Dart and David Rafferty, gave a paper on the unwillingness of the Roman aristocratic elite to reform republican institutions and the ways in which this led, step by step, to upheaval and revolution. In an era of growing economic inequality and political sclerosis, this was not only topical, it was actually more illuminating than, say, a dissection of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Harvard University Press, 2014) because of the depth of perspective.

They observed:

“In 51 (BCE) on the eve of the civil wars that would deal the final blow to the most powerful and enduring republic of the ancient world, Cicero observed (in his classic book on Roman politics De Re Publica) that what he felt was the finest example of a carefully calibrated mixed constitution could only ever come undone through ‘great faults in the governing class’.”

That, of course, is exactly what had been happening and did happen. They then quoted Robert Reich as observing, in April this year, almost exactly the same about American elites. The link between current concerns and the original reflections on the nature of politics by Plato and Aristotle was electrifyingly evident.

Their paper was immediately followed by Francisco Pina Polo of the Universidad Zaragoza, Spain, on Political Polarisation and the Fall of the Roman Republic. He drew a direct analogy between the atrocities carried out by Franco’s fascists after their victory in the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) and the savage proscriptions (purges) by Sulla, in Rome, after he had won the civil war against Marius (83-82 BCE) – the first actual civil war in the history of the republic.

Sulla stood for the old order and Marius for the populist reform party. Having defeated the latter, Sulla had an estimated 9000 of his fellow citizens summarily executed and their property confiscated.

There are armed militias in the United States now threatening and even calling for civil war. The discussion of Sulla was anything but “academic” in the pejorative sense. Yet it was academic in the most profound and refreshing sense.

Kit Morrell, from the University of Queensland, gave a paper on “Enabling laws”, rule of law and the transformation of the Roman Republic, exploring the process by which the old practice of appointing a dictator for a single year of crisis gave way, in the course of the last century of the republic, to enabling laws conferring extraordinary powers on individuals like Sulla and Caesar until, at last, the republic ended up with Augustus as dictator for life. The conceptual link between classical Rome and the writings of the Nazi legal theorist Carl Schmitt leapt to mind.

One of the most exquisite papers was by Cristina Rosillo Lopez, of the Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Seville: Dealing with Uncertainty: Cicero, Victor Klemperer and how to cope with the present in moments of crisis. Drawing on Cicero’s letters to Atticus (and others) as Caesar and Pompey duelled for primacy in the Roman world, and on Victor Klemperer’s diaries of 1933-45, while precariously surviving as a Jewish intellectual in Nazi Germany, she showed that we have to be careful not to assume, in hindsight, that intelligent people, at such points in history, knew what was going to happen even a few years later.

The moral of the argument is that we, right now, might tell ourselves that we know how things are going to turn out, but in truth we are guessing and perhaps guessing wrongly. We project our fears or hopes and our limited insights or grasp of the facts on to the imagined future and make our choices accordingly. Others do the same, chance plays its part and things turn out, very often, rather differently than we had expected – sometimes better, sometimes worse. We do have agency, but we do not have clear foresight – even where we believe we do.

All this is and ought to be cherished as the larger conversation in which we live and breathe. It was this scholarly and cultural context within which Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay discussed, in a series of letters published in the newspapers of New York City between October 1787 and August 1788, the principles which should guide the founding of an American republic. Their thinking is being seriously tested now – as Donald Trump faces multiple indictments.

Though Hamilton, Madison and Jay contributed various letters, each letter was signed “Publius” – as if by the same author. Each was about the public good, the public “thing”, the res publica, from which Roman term we derive the very word republic. Those letters, 85 in number, became a classic known as The Federalist Papers. They are a close reflection on what makes representative and accountable government both possible and durable. They hovered right on the edge of last month’s conference.

Hyun Jin Kim, a polished Korean scholar currently based at the University of Melbourne, delivered a paper called The Fall of Athens’ Democratic Empire. His family history is bound up with the history of a divided Korea: tyranny in North Korea and dictatorship followed by democratisation in South Korea. For him, too, the debates from the classical Mediterranean republics have resonance and relevance.

That a Korean scholar gave a paper on Athenian democracy at a conference in Melbourne is a significant pointer to how far the world of political philosophy has come since the fall of the Athenian empire. And he was exquisitely attuned to the nuances of the matter. He did not speak in hoary cliches. He showed that how democracies die and how they flourish is not a classical Western concern, but a universal contemporary one. Conversation with him was a pleasure.

Do such conferences hold immediate solutions to our problems? No. Those can arise only where dialogue of this kind underpins institutional wisdom and public debate, the principles that guide public policy formation and the choices of voters. What the conference demonstrated, to my relief, is that our academic institutions are not wholly overrun by ideological rancour, identity politics or other politically correct nonsense. That I was pleasantly surprised by this is worrying.

Paul Monk is a Melbourne-based writer and poet. He graduated from the University of Melbourne in 1981 with a First-Class Honours BA in European History (ancient, medieval and modern). He is the author of a dozen books, including The West in a Nutshell: Foundations, Fragilities, Futures (2009) and Dictators and Dangerous Ideas (2018).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout