An epic Endeavour, a vexed debate about Captain Cook voyage

James Cook’s voyage was a testament to science. There are many monuments and statues lauding him, but no similar monuments honour the ancient discoverers of this land.

It was one of the most hazardous explorations in the history of the sea, and this year is the 250th anniversary of its high and low points. How it will be celebrated in Australia, the main beneficiary of that voyage, may well become a burning question.

James Cook, aged 39, had sailed from the English port of Plymouth in August 1768. His naval ship Endeavour, which originally carried coal along the east coast of England, was a three-masted barque no larger than a tennis court. Calling here and there at Atlantic ports his wooden ship reached the stormy tip of South America and then ventured into the windswept waves of the South Pacific Ocean.

Cook’s voyage was testament to Europe’s fascination with science. His first destination was Tahiti because its cluster of islands was favourable for observing the rare transit of Venus, an astronomical event that would take place for six hours on Saturday, June 3, 1769. The event would not occur again for 105 years. To observe it accurately, in many different parts of the world, would provide valuable information for navigators.

Curiously, this voyage also foreshadowed today’s China-US rivalry. However, in Cook’s heyday France and Britain were the world’s great powers, and France held more people than did any other nation in Europe, Africa or the Americas. For these two powers the South Pacific was like the South China Sea is for the two great powers of today. Indeed, the South Pacific region was the more important because it was believed to possess, far out in the unexplored ocean, a huge inhabited continent rich in gold and tropical plants and the home of enterprising Jewish merchants.

Popular science backed this faith. It seemed self-evident to anybody of intelligence who scanned the map or fingered a model of the world on their office desk. Whereas the map displayed vast expanses of land north of the equator, it seemed to show few lands to the south. Balance surely demanded that there be an equal weight of land in the southern and northern hemispheres.

In Paris and London it was obvious that the first nation to plant its flag on the lost continent would be enriched and its navy and merchant fleet would be multiplied. Thus Cook, after his days in Tahiti were over, read his secret instructions to search for the missing continent. And search he did, week after week.

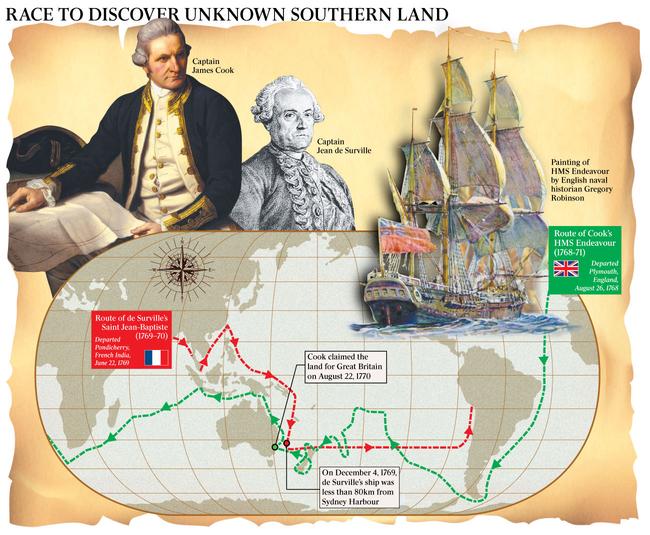

The French, too, organised their search. Commanded by Jean de Surville, a naval captain more experienced than Cook, the French ship St Jean-Baptiste was twice as large as Cook’s. Departing with a large cargo of trading goods from the French colony of Pondicherry in eastern India it followed a zigzag route — with many mishaps and deadly bouts of scurvy among the crew — to the Coral Sea and then the Tasman Sea. By the end of 1769 it was coming closer and closer to Cook’s Endeavour, making its own search.

It is one of the little known but tantalising events in Australian history that de Surville for a time led Cook in the discovery race. On December 4, 1769, de Surville must have been near the not-yet-discovered Sydney Harbour. For several hours his officers recorded the distinctive odour of land. In their own words “we smelt a scent of meadow, like dry hay”.

Nowadays when we arrive in Australia in air-conditioned aircraft we are deprived of a smell that, in the era of sailing ships, was so familiar to thousands of migrants. Coming from Europe with no sight of land for several months, the immigrants in sailing ships often sensed the presence of land when they approached Cape Otway, at the entrance to Bass Strait and the final sea approach to Melbourne. Again and again these immigrants sniffed land an hour or two before they could see it.

On this early summer day, December 4, 1769, de Surville’s ship was less than 80km from Sydney Harbour. This was nearly five months before Cook, coming from the opposite direction, reached the vicinity of Botany Bay and the adjacent Sydney Harbour. But the Frenchman was in a hurry. As the nautical books in his cabin denounced the arid western coast of the continent, de Surville assumed that this east coast and its dark people were like those seen so often by Dutch navigators on the west coast. He resolved to change course and leave Australia behind.

One week later he was in sight of New Zealand. His next destination was the Jewish harbour in the lost continent — if he could find it. His final destination was to be the coast of Peru; and there, dressed in his naval uniform, along with medals and ceremonial sword, he was accidentally drowned while seeking help for his scurvy-sick sailors.

Cook and the bushfire coast

Will the anniversary of Cook make this year more a time of celebration or more a time for indignation? The Cook celebrations in 1970 — the 200th anniversary — passed off peacefully and proudly. They came just after the first landing on the moon. Understandably, Cook was eagerly hailed in 1970 as an earlier discoverer of an important land mass: a kind of astronaut who arrived by sea. He was not yet condemned as an evil invader by articulate Aboriginal leaders. Their crusade for land rights had barely begun, though it was on the agenda of the Labor Party, which under Gough Whitlam was soon to win office in Canberra.

I recall the celebrations, in mid-April 1970, of Cook’s first sighting of the east coast of Australia. Sir Henry Bolte, the longstanding premier of Victoria, had organised a special train and as a historian I was one of a couple of hundred citizens invited to travel from Melbourne to East Gippsland. We sped through the night and at Orbost the next morning the buses were waiting to convey us on the long trip to the lonely granite headland named after Zachary Hicks, the London-born sailor who first saw this coast.

Rising young federal minister Peter Nixon, an Orbost boy, spoke for the commonwealth amid the muted roar of the ocean, and we heard Bolte making his speech from a little sheltered platform erected near the tall white lighthouse and the keepers’ cottages. Perhaps a few Aborigines were present, but not many. It was easy to imagine the Endeavour sailing north in April 1770 in the direction of the unknown Sydney Harbour.

That same coastline has dominated the news, even the world news, this month. The present scene of a procession of frightening bushfires was, in the eyes of Cook, virgin forest and bushland with the occasional green clearing or coastal patches of sand. Even then it displayed small but manageable bushfires.

In his journal Joseph Banks, the star botanist, often noted the presence of what he called “smoak”. At night on April 21 he reported seeing five fires. On the following three days the crew saw various fires, though at times their ship was so far from the shore that it could not serve as a grandstand. Near Bateman’s Bay, however, it was so close to the beach that through his telescope Banks could see the faces of five people whom he described as “enormously black”.

Almost certainly these coastal fires were lit by Aboriginal people. In modern jargon most would be described as attempts at hazard reduction. Definitely they were not bushfires burning out of hand, though just occasionally a catastrophe must have happened here in the course of past millennia, no matter how skilled the local Aborigines were in managing fire.

Australia was only the second prize

It is easy to forget that the discovery of our east coast was, in one sense, a relative disappointment for Cook and his scientists. They had been hoping, for nearly two years, to discover something bigger and richer, the mysterious southern continent. Just two months before the Endeavour reached the Australian coast, several officers had believed they might still set eyes on that mighty missing continent that we now know does not exist.

Lieutenant John Gore, a most experienced officer, even announced that he saw across the sea the long-sought land. Cook’s telescope, however, proved that it was just a bank of cloud squatting low on the horizon. Gore was so persistent that Cook changed course and sailed towards the imagined land from noon until 7pm before giving up hope.

Banks almost alone remained a true believer. Now that he began to look at the Australian coast he was almost lost in wonder, though initially he thought this new land was just a second prize. At last the Endeavour entered the neck of Botany Bay and anchored there for just over a week. On several sunny days, well-armed British exploring parties set out to see the creeks, grasslands and scrub. Banks and his Swedish colleague Daniel Solander collected a mass of new plants — one of the most fruitful weeks in the whole history of botany. And attempts, mostly friendly, were made to meet local Aboriginal people, who in turn were not very keen to be met.

Nanny goat and kangaroo

An unusual visitor to Botany Bay does not find a place in Australia’s history books. A nanny goat, perhaps the most travelled animal in the world, had been led aboard at Plymouth to provide milk for the officers; and here she was, nearly two years later, alive and well at Botany Bay. As she craved fresh grass she was doubtless allowed ashore, a rope around her neck, while sailors gathered hay-grass to carry aboard.

About one in four of the original crew was to die during the long voyage but this hardy goat survived. Finally reaching London she was walked, much marvelled at, to the eastern suburb of Mile End where she was welcomed and cared for by Cook’s wife, Elizabeth. Before long poet Samuel Johnson was invited to compose a short Latin verse in honour of Nanny, and it was inscribed on her silver collar. Translated into English the words proclaimed: “This Goat, who twice the world had traversed round.”

But to return to Botany Bay in 1770: the Endeavour, with the goat safely inside her pen on deck, sailed slowly past the entrance to Sydney Harbour. The evidence suggests that Cook could not see, even with the help of his telescope, that this was one of the world’s finest harbours. But recently a Sydney lawyer, Margaret Cameron-Ash, has argued in a bold book that Cook already possessed an insider’s knowledge of the harbour that was to be so crucial to Australia’s modern beginnings. He kept the knowledge to himself and disclosed it only to the British Admiralty when at last he returned to London.

The new book is called Lying to the Admiralty. You can already guess why Cook reportedly told a lie. His wish was to prevent the inquisitive French from learning about such a strategic, capacious and easily defended harbour standing at the far end of the world.

The Endeavour, leaving Sydney far behind, followed the coast towards the tropics and Cook made his sea charts with remarkable accuracy by the standard of the times. Rarely, however, did he go ashore. In the vast expanse between Sydney and Cooktown he landed only once — at what is now the small Queensland township called 1770. Further north, he went aground, though unintentionally. On a moonlit night his ship hit a coral reef and was almost wrecked.

His only long stay on the Australian coast was not at Botany Bay but on the banks of the Endeavour River where the present Cooktown stands. There his ship was repaired. Not far away the first kangaroo was seen, captured and described, and its local Aboriginal name, gangurru, slightly misheard by Banks, entered the many local languages of Australia and the other side of the far-off world. This first kangaroo was cooked “for our dinners”, wrote Banks.

Cooktown might well have become one of the first British settlements in the continent but for the problem of the Great Barrier Reef. We want to save the reef. Cook wished it did not exist. It nearly wrecked his ship again when he sailed north towards Torres Strait.

After a long stay in Jakarta and another in Cape Town, the sturdy ship reached the English Channel in July 1771. It had been away for nearly three years. The humble farmer’s son privately reported that he had made no notable discovery during his dangerous voyage across three great oceans. He regretted that he had failed in that vital task: to find the mysterious continent. He had no idea that he and his men indirectly were to alter forever the history of Australia and New Zealand.

What should we cheer for in 2020?

Cook will be honoured this year in Australia. He will also be condemned. The public’s response will partly be a barometer of the current tensions and hopes centred on Aboriginal affairs.

There will be opposing arguments and both, in moderation, are legitimate. Cook was a giant of the sea. To deprive him, his scientists and his crew of high praise would be mean-spirited and would mock history. He was almost certainly the first European to sail along and report on nearly all the eastern coast of Australia. He indirectly made possible present-day Australia which, despite its many failures, is surely one of the success stories of the world.

On the other hand, Aboriginal peoples will rightly insist that they, or people close to them in kinship, were the first discoverers of Australia. Their ancestors, one after the other, had sailed and walked along the Indonesian archipelago, a chain of stepping stones that were easily used when the world’s sea levels were lower. In a series of short voyages perhaps spread across several thousand years they bridged the gap between Southeast Asia and Australia. In the early history of the land they discovered and settled they have a proud role.

There are many monuments and statues to Cook, many places on the map that honour him and his crew. No similar monuments honour the ancient discoverers of this land. Aboriginal leaders have failed to take up suggestions, officially made as long ago as 1975, that they should erect their own discovery monument, though money could easily be found.

This year the federal government should step in. It should make the decisions, architecturally and geographically, on behalf of all the peoples of Australia, irrespective of ancestry and background.

We do not know where the first Aboriginal peoples came ashore. The landing place is now almost certainly under the ocean. It was made before the great rising of the seas, at a time when Australia and New Guinea and Tasmania were one land, and an early Australian family could in theory walk all the way from Perth to Manus Island or from Hobart to Port Moresby.

That vast gap in our knowledge makes it easy for Canberra to choose a symbolic site — or perhaps four separate sites — where a fitting discoverer’s monument could arise.

In 1966 Geoffrey Blainey first wrote at length on Cook in his book The Tyranny of Distance. His recent book on Cook, entitled Sea of Dangers (2008), will be issued in revised form in March by Penguin Random House.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout