An education in university funding reform

Dan Tehan’s ambitious fees reform creates ‘perverse incentives’ for universities.

The dramatic changes in university fees announced by Education Minister Dan Tehan last week have caught the attention of families, particularly those with children in the final years of high school.

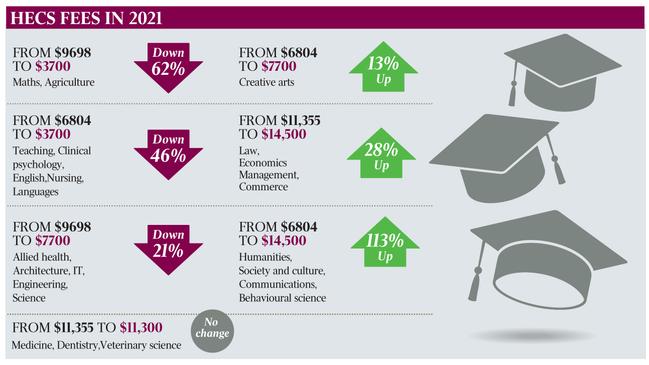

Low fees of $3700 a year for teaching and nursing courses will please many, but not so welcome to other students is the colossal 113 per cent price hike for humanities degrees, although fee rises will not affect current students.

But behind these dramatic headline fee adjustments is an attempt by Tehan to introduce major reform to university funding, which could lead to significant change in the structure of the higher education system. In the next four years tens of thousands of new student places must be added to Australia’s higher education system to ensure the children of the Costello baby boom — born in the mid-2000s — can go to university.

This comes as the COVID-19 pandemic, and the resulting loss of international students, has cut universities’ revenues by several billions of dollars a year and forced them to shed thousands of jobs.

But that’s not all. Federal cabinet is adamant that, during this time of record government budget deficits, it will not boost university course funding beyond the very modest increases projected in the budget forward estimates out to 2023.

Tehan’s funding plan could take as its mantra “Never let a crisis go to waste”, because it’s an audacious bid in these trying times to reconcile these conflicting goals.

“It’s a complex package. It’s trying to do a number of difficult things simultaneously,” University of Wollongong vice-chancellor Paul Wellings says.

To meet the “baby boom” demand it boosts the number of government-subsidised university places by 39,000 in the next four years. But, to achieve this in a time of budget constraint, the cost is not borne by the government. Instead, students pay more and universities are asked to stretch their resources more thinly. So despite the fact fees for nursing and teaching degrees will drop, average student fees will rise 7.8 per cent from $8644 to $9319. And universities, already reeling from the impact of COVID-19, will get less government subsidy for teaching each student. It will fall by 16 per cent from an average of $11,953 to an average of $10,070 a student per year.

The blow is softened by the return of annual indexation for government course subsidies, which was taken away in 2017, and the creation of several other pots of money including a $700m fund to help universities move to the new system and a $900m fund to be spent on research and matching skills with industry need. In normal times universities would scream blue murder at the treatment they are getting in the Tehan funding package. But these are not normal times.

While the Group of Eight universities express disquiet at the heavier burden on students, they also acknowledge the need for sacrifices. “We recognise that out of COVID has come the need to embrace a level of pragmatism for the long-term national good. This is one such moment in time,” Go8 chief executive Vicki Thomson said after Tehan announced the package.

If Tehan had wanted to do the minimum he would have just offered up a plan that simply raised all student fees and reduced government course subsidies by a fixed percentage. This would have been the approach of least risk, easily justified by the emergency circumstances he faces. But he decided to pitch far higher, and it is on the other, more complex elements of his plan that he will be judged. His main goal is set out in the title of his work, the Job-ready Graduates Package. He is trying to shift student choices towards degrees he believes will be needed for the 21st-century economy.

Tehan says the package will “incentivise students to make more job-relevant choices, that lead to more job-ready graduates, by reducing the student contribution in areas of expected employment growth and demand”.

A key part of the plan is the 21 per cent fee drop for degrees in engineering, information technology, science, health, architecture and environmental science. But to achieve these fee reductions, in a package that hikes student fees overall, the cost of other degrees has to go up. Which is why society and culture degrees (including social work) and humanities degrees rise 113 per cent to $14,500 a year. It’s also why degrees in law, economics and business rise to the same level.

This is controversial and one of the areas in which Tehan may fail to win the crossbench support in the Senate he will need to get the package passed. For example, today’s engineers increasingly need cross-disciplinary skills.

“Double degrees are very important for a really well-rounded engineering graduate. We see a lot of them taking engineering-law or engineering-arts,” Engineers Australia chief executive Bronwyn Evans says. And the package makes these types of degrees more expensive.

Tehan has another aim in reforming the funding system. He wants to ensure that, in the longer term, the total revenue universities receive for a course in a particular subject roughly balances what it costs to teach. This is a worthy goal because it removes the incentives for universities to recruit students into courses that deliver more profits, instead of those that produce the skills students want and society needs.

Accordingly, the minister’s plan will adjust the subsidy amount the government offers for each type of course, with the goal of ensuring the revenue received by the university (student fees plus government subsidies) is as close as possible to the cost of teaching.

But this creates problems too. For example, the revenue universities get from science, engineering and nursing courses currently is well above the cost of those courses, according to data the government is using from a report Deloitte did last year.

So, with universities set to receive lower revenue from science courses, they will have an incentive to restrict student numbers, which is the opposite of what Tehan wants to achieve.

“The really big questions will be around expensive (science) subjects like chemistry,” says Wellings. “The challenge will be to make sure there is not an attrition of those skills around the country.”

There’s another related problem that stems from the high $14,500-a-year fee planned for law, business and humanities courses. The student fee is so high that the government will tip in only another $1100 in subsidies for each student. That gives universities the option of recruiting many more students in these areas because they can probably make the courses pay for themselves on the student fees alone.

It’s a “perverse incentive”, Australian National University vice-chancellor Brian Schmidt says, and the opposite of what Tehan wants to achieve. Apparently realising the danger it poses, Tehan announced this week that the higher education regulator, the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency, would be given powers to intervene if universities over-recruited in high-fee subjects.

The final test will come when Tehan negotiates the package with the Senate crossbench. With Labor and the Greens likely to oppose it he must win three votes from a selection of two One Nation senators, two from the Centre Alliance and Jacqui Lambie. Changes to the package are probably on the cards.

Even then, it’s not over. Tehan’s package is aimed at reforming the way teaching is funded in universities. But that’s only half the story. The other half is research, and the funding problems there are even more dire than in teaching.

Research is highly reliant on international student fees, which this year will drop by at least a third from last year’s total of more than $9bn across all universities. This particularly hurts the Go8 universities, which pick up more than half of the pool of international student fees and do two-thirds of the nation’s university research.

So Tehan’s next project is to find a solution for the research funding dilemma. The process won’t be pretty. Nobody believes the government will put any more money into the research funding pot. It will be a matter of dividing up what is there in a different way.

The most sensible solution is to spend the available money on the highest value research. But what is high value? Is it academic excellence demonstrated by publications and citations, engagement with business, or community impact? How to do you measure the latter two more nebulous concepts anyway? Universities also want a funding system in which research grants fund the full cost of a research project, not force them to scrabble for extra money elsewhere.

The Go8’s Thomson says “everything must be on the table” for discussion. “In a recession context, we must ensure we get the best bang for our buck and an outcome which focuses on research excellence and delivers in some way full economic costing of research,” she says.

Once Tehan sorts through this thicket he will make a statement on research funding reforms. It is expected to be ready before the October 6 budget.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout