America's sunshine act fires hope in Australian daylight saving fight

Could a push in the US to make daylight saving permanent catch on in Australia?

In the US, the debate over daylight saving has taken an unexpected turn since Congress’s august upper house, the Senate, abruptly passed legislation in March to make summer time permanent.

For once the people’s elected representatives had conducted themselves with a minimum of fuss or partisan foot-dragging, compounding the surprise that a measure so rich in meaning for everyday lives and livelihoods could be waved through by politicians.

Of course, it might yet be another false dawn in the century-old daylight saving saga. The Sunshine Protection Act could well come a cropper in the US House of Representatives, where it’s business as usual with battlelines being drawn on the well-traversed contours between city and region, primary producers and urban professionals.

The question for us is, could it fire up the largely moribund campaign in the holdout jurisdictions of Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory to adopt daylight saving?

The small but determined band of activists and civic leaders striving to keep the issue alive will certainly do all they can to leverage the American gambit.

“I’m convinced daylight saving will deliver an incredible bonanza for our local tourism and hospitality industries, while also directly benefiting businesses that operate across borders,” says Brisbane Lord Mayor Adrian Schrinner. “Late former Queensland premier Wayne Goss was right three decades ago when he warned this debate won’t go away.”

In WA, the torchbearer is MP Wilson Tucker, whose Daylight Saving Party propelled him into the upper house of state parliament on a niche return of 3485 votes at last year’s general election. The hope of the side is that, as in the US, the disruption of the annual time change in NSW, Victoria, South Australia, Tasmania and the ACT on Sunday will whet the public’s appetite for unifying action.

Tucker is drafting private member’s legislation that he plans to introduce at the first available opportunity next year – even though Premier Mark McGowan, wielding one of the strongest parliamentary majorities in Australian history, promptly pronounced the bill dead on arrival.

WA Health Minister Amber-Jade Sanderson, a supporter of change, agreed there was no enthusiasm for a fourth go at bringing the state into the fold. “It’s not something that I think is front of mind for the broader community,” she said recently, echoing McGowan. “Daylight saving is just not an issue that people approach me about regularly.”

WA Opposition Leader Mia Davies dismissed it as a distraction.

Predictably, Tucker argues that the Sunshine Protection Act has the potential to breathe life into the cause. “It could act as a signpost for Australia,” he says. “If it were to work for a country like the United States, which has multiple time zones, then it can definitely work for Australia. I think we are going to see this discussion happen again over the summer and I think that’s a good thing.

“Here in the West … we’ve undergone a lot of changes since the last referendum in 2009 and I also think Covid has shifted expectations of what governments do … that they need to sometimes be decisive and act on difficult issues.”

What he’s getting at is how the 100-strong US Senate stood up as one and did something bold to settle a dispute that has been simmering on and off since World War I, when daylight saving first came in.

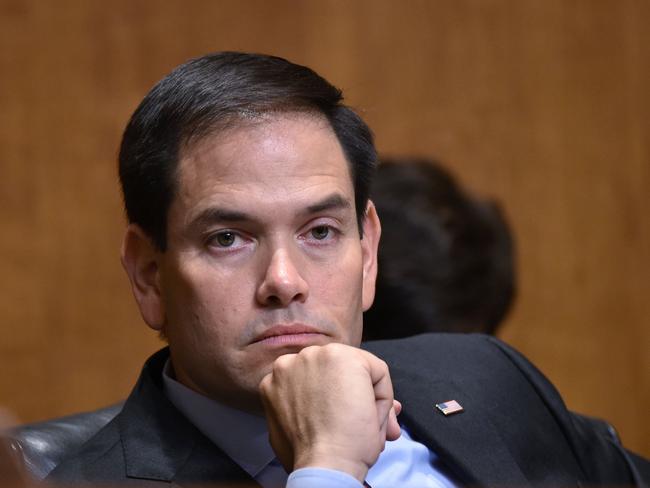

Imagine that! The legislation was introduced on March 15, two days after the annual “spring forward” to the later sunsets of daylight saving time, by high-profile Republican Marco Rubio, a contender for the presidential nomination seized by Donald Trump in 2016. Not coincidentally, Rubio represents sunny Florida and is keeping his options open for another tilt at the White House in 2024.

At first blush, the bill’s prospects appeared bleak. A bipartisan group of senators had tried and failed, for congress after congress, to freeze the clocks and keep the country on summer time permanently. But this time it sailed through unanimously, so fast some senators later professed to be unaware of exactly what had happened.

Democrat Kyrsten Sinema, presiding over the chamber at the time, was heard to exclaim: “Oh, I love it.” She’s from Arizona in the southwestern sunbelt, the only state that doesn’t observe daylight saving alongside Hawaii.

The New York Times speculated that there was a very human dimension to the unaccustomed outbreak of political peace: after losing an hour’s sleep on the preceding Sunday, grumpy senators were as fed up with the disruptive time change as voters were.

Rubio said: “If we can get this passed, we don’t have to keep doing this stupidity any more. Why we would enshrine this in our laws and keep it for so long is beyond me.”

But as they like to say in congress, the rubber has now hit the road. Americans will gain an hour at the start of their day when the clocks go back in most states for winter on November 6 under existing arrangements. As the implications of the Sunshine Protection Act are teased out, doubt about year-round summer time is gaining traction.

Consider what would happen in New York City. On the year’s shortest day, the December 21 or 22 winter solstice, sunrise would be an hour later at 8.16am. Kids would not just leave for school in the cold and dark, the first lesson would be over with before it was fully light outside. (Classes generally start at 8am in the US.)

Farmers and the parents of small children cite grievances familiar to the debate in Australia – by necessity they rise with the birds, not a clock – and the changeover for summer is disruptive enough without making it permanent.

The only time full-time daylight saving has been tried before, in 1974 in what was supposed to be a two-year trial backed by Richard Nixon to conserve petrol at the height of an energy crisis, the scheme failed within nine months and was abandoned by the disgraced president’s successor, Gerald Ford.

The warm glow among politicians seems to have faded, with political journal The Hill reporting the bill had hit a “brick wall” in the house, where it has yet to find a slot on next year’s sitting calendar.

Fundamental disagreements over the language of the legislation and a “general consensus” that Congress had more important matters to work through – soaring inflation and war in Ukraine among them – has killed the buzz, defeating those early, tentative efforts to reach across the aisle.

While house Speaker Nancy Pelosi supports the Sunshine Protection Act, congressional Republicans and Democrats are increasingly at odds over what the permanent time should be: daylight saving or standard, as in Russia, where summer time was axed by Vladimir Putin in 2014.

Brazil limited daylight saving to southern and central-west provinces in 2019, while Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador in July sent legislation to the national parliament to ditch it and return to “God’s time”.

Still, public opinion in the US is hardening against the seasonal resets. A Monmouth University poll in March found 61 per cent in favour of permanent time, one way or another, compared with 35 per cent for the existing hybrid arrangement. YouGov found 59 per cent wanted full-time daylight saving time against 19 per cent who did not.

The trouble in Australia is that most of the political class think of the issue as a dead duck. Queensland Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk is on the record admitting that she personally likes daylight saving but repeatedly has resisted calls to act. Her office told Inquirer her position was unchanged.

The Chamber of Commerce and Industry Queensland, which warned as recently as 2018 that the cost to business of the state staying out of summer time topped $4bn annually, is no longer agitating for change. Even on the Gold Coast, traditionally ground zero of the angst, there’s grudging acceptance that it’s yesterday’s news. “It’s not an agenda item that we’re pushing as a lobby platform,” says Martin Hall, president of the tourist strip’s central chamber of commerce.

If anyone with clout were to be swayed, you would think it might be the Queensland Liberal National Party’s Gold Coast-based leader, David Crisafulli.

His electorate is barely an hour’s drive from the NSW border. Crisafulli, though, was formerly a Townsville MP and minister in Campbell Newman’s single-term LNP government who slapped down calls for a daylight saving trial in 2014, one of the numerous attempts to get one up after the last referendum under Goss foundered 30 years ago on a 54.5 per cent No vote.

Crisafulli insists the question is moot and will stay that way.

“I have lived and worked at both ends of our great state,” he tells Inquirer. “I want to unite Queensland, not divide it. That’s why it’s not on the agenda.”

Tucker, for his part, says a key lesson from the US is that politicians must do what they’re paid for, and lead, if there’s to be movement on daylight saving in the have-not jurisdictions. As is the case in the Sunshine State, successive referendums in the West have failed – the last attempt in 2009 going down by the same, relatively heavy 54.5-45.5 per cent margin as the 1992 Queensland vote. Tucker’s private member’s bill dispenses with that, leaving the decision to parliamentarians, just as it was in the conscience votes on voluntary assisted dying that rolled out across the nation after Victoria blazed a trail in 2017.

“The truth is we trust MPs to make decisions on behalf of constituents and on behalf of the community every day,” he says. “This is another example of where we should be.”

What’s that Yes Minister’s Sir Humphrey Appleby said about “very brave” politicians? Whether you like summer time or not, don’t hold your breath for them to come together here, not when it’s so much easier to argue that people are over daylight saving.

It’s that time of year when two-thirds of the country puts the clocks forward an hour and the rest doesn’t. But what if there were a better way to make the most of the lengthening days?