Albanese’s first shot in election workplace battle backfires

Labor will fight the election on industrial relations. It is already in serious trouble.

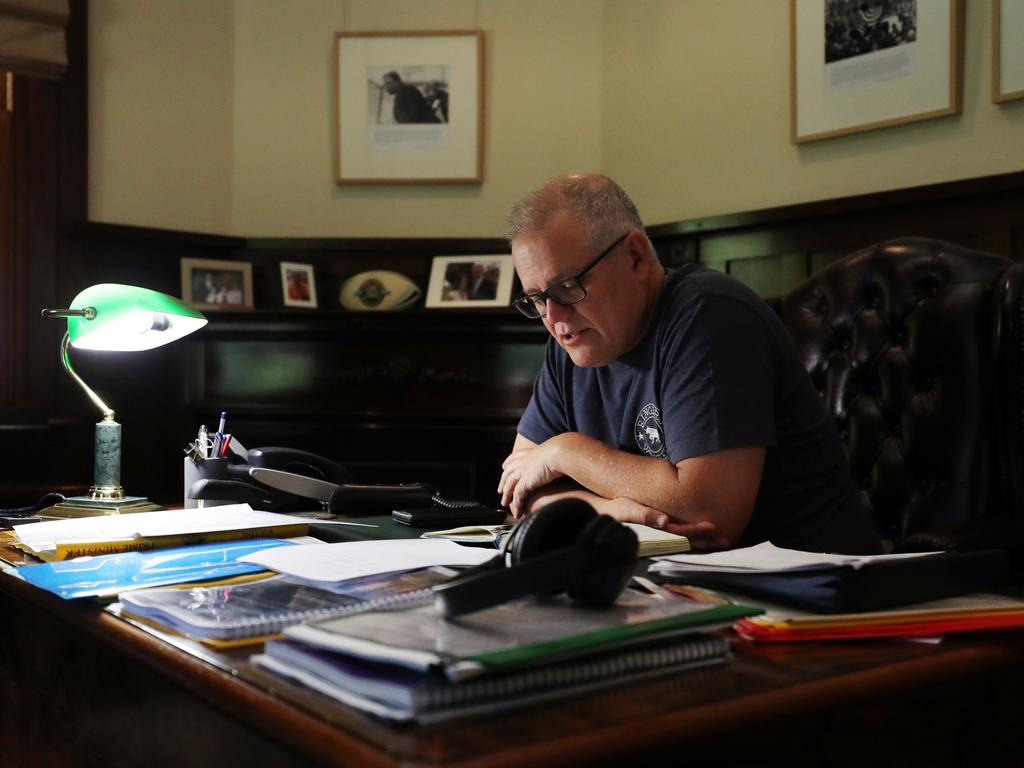

Albanese’s aim is to refurbish his stocks with both the public and the party. This week, he hung round Scott Morrison’s political neck the accusation that he is using the pandemic to encourage “the creeping expansion of insecure work” — with nearly a third of Australian workers at risk from “unpredictable, fluctuating pay and hours” and having few or no protections for sick pay and holiday leave.

The terrain for the next election is taking shape. Albanese is walking away from former leader Bill Shorten’s tax-and-spend 2019 election agenda and shifting industrial relations to centre stage. The proofs are on the table.

Albanese recently dismissed any change whatsoever to franking credits — branded by the Prime Minister last campaign as a “retirees tax” — thereby expelling big spending and big taxation as the ALP’s central theme. This week, he tapped into what Labor sees as the community’s pandemic-induced longing for security to build a new IR policy that condemns job insecurity and seeks structural change in the labour market to deliver a higher proportion of secure jobs.

Labor’s workplace spokesman Tony Burke told Inquirer the coming election would “easily” involve the most significant IR differences since the 2007 Work Choices poll. “It’s 30 years since Australia has had a recession,” Burke said. “When the nation comes out of a hole, more jobs are created. This is that moment in time when Australia will decide what those jobs look like — whether they are secure or insecure.

“There has not been a time for years when industrial relations is going to be more potent politically or more relevant for the nation’s economy. People will have the confidence to spend providing they know their household income is secure.”

Asked if ALP policy meant the proportion of casuals in the workforce would fall, Burke said “yes”. Asked what percentage it should fall to, Burke said: “I don’t have a magic number.” But Labor’s industrial relations rollout this week faced two problems highlighting how much the world has changed since the Howard-Rudd Work Choices era.

First, the Morrison government has no intention of running a radical IR policy (witness its current reform package before the parliament). The intent of Scott Morrison and Industrial Relations Minister Christian Porter is to negotiate the best compromise they can get, legislate the deal and put IR out to political pasture long before the election. With one exception, sure to be abandoned, their reforms are modest, practical and largely non-ideological.

Second, Labor got into serious trouble this week with its policy rollout and was forced into backtracking — the message being that its pledges to deliver a more regulated, job-secure, less-casualised labour market is a threat to business, job recovery and Labor’s economic credentials.

IR is no longer the easy picking for Labor it once was. Australia’s more diversified 21st century workplace means Labor’s pro-union approach to IR cuts both ways: more security appeals to workers; but it calls into question Labor’s grasp of the needs and nature of the contemporary economy.

Innes Willox, head of the Ai Group, the main industry lobby, told Inquirer: “There was no consultation before this policy was released. It has nothing for business. It is all cost, all barriers. There’s nothing for us to negotiate around, nothing we can work with. This policy takes us back to a 1960s-style 9 to 5 workplace, which is unsuitable for a 21st century economy.”

Porter could hardly believe Albanese’s speech. “They are stuck in an ideological space where they think they know the best type of employment for Australians,” he told Inquirer. “They have had years in opposition but they still cannot tells us what their definition of a casual is. That is hopeless. They are promising portable entitlements for 3.5 million people in insecure work without any assessment of the cost.

“This is the same mistake Labor makes election after election, leader after leader. Their answer is always a massive tax to fund utopian promises in the hope of winning votes. Labor’s problem is they don’t understand the economic impact of the policies they advocate.”

On the contentious pledge in Albanese’s initial draft to “work” with state governments, unions and industry to develop “portable entitlements for annual leave, sick leave and long service leave for Australians in insecure work” — an open-ended statement that Porter cost at $20bn — Burke subsequently told Inquirer: “Effectively, our commitment at this point is similar to the commitment when the government set up the working groups on industrial relations, where they identified what they considered to be problems and said we are going to consult.”

In short, it is aspiration, not policy. Albanese’s speech said Labor would achieve such portability “where it is practical”. An open-ended declaration was turned into an open-ended qualification.

Porter points out the epic nature of the original stance: if all casuals and contractors were given portable annual, sick and long-service leave, rights not extended to all permanent workers, then Labor was offering “the most costly promise in the history of industrial relations with no details and no analysis of the impacts”.

The clarification from Albanese and Burke took any such commitment off the table. “There are many industries and examples where there will not be a practical way through,” Burke said. “But I’m confident there are some specific areas where we can make further announcements but we will have the consultations.” This leaves the aspiration swinging in the wind, along with the cost to business.

Porter’s office released the $20bn calculation showing it was based on ABS data of 2.3 million casuals and 1 million independent contractors at August 2020, and then calculated with separate assessments for annual, personal and long-service leave.

“The only person who has designed that policy is Christian Porter, not Labor,” Burke said of the minister’s assessment. “I am very confident the battle lines for the next election will be both sides talking about jobs, but where the mantra of Mr Morrison will be job numbers Labor will be talking about the value of secure jobs.”

Yet there was a second “clarification” to Albanese’s policy. His speech praised the contentious Dan Andrews Victorian government decision for a pilot scheme to provide sick leave for some casuals with the provision that any “ongoing scheme” would be financed by an industry tax. At the time, Porter branded the Andrews proposal a “business- and employment-killing approach”.

But Albanese praised the Andrews policy, saying: “My colleagues and I see this work as a valuable first step.” Asked if federal Labor endorsed the Andrews government position, Burke clarified the situation. He said Andrews had acknowledged “a very real problem” but added: “We are in no way signed up to how he sought to solve it.” Asked directly about a levy on business, Burke said: “It’s not something I’ve considered.”

In short, federal Labor won’t be following Andrews.

The message is obvious. Making big claims about improving conditions for insecure workers is fine rhetoric but plagued with costs and consequences. Who bears the costs? What are the consequences for jobs? Does Labor want the tag of being the business tax party in the cause of casual worker entitlements?

Asked about the business criticism, Burke was philosophical: “It’s very rarely been the case that the major business groups have been in favour of policies that make work more secure or that deliver better pay. That’s simply a fact of history.”

Yet a feature of the speech was Albanese shunning the class warfare rhetoric heard so much in past years from both Shorten and Wayne Swan. Albanese talked about the need for a “partnership between government, business and unions” — but this highlights the point and paradox made by Willox: there was actually nothing in its content for business.

Albanese’s policy is closely aligned with the ACTU campaign for more secure work. Its foundational idea is that flexibility must not come at the cost of security.

Burke said Labor wanted two results for casuals: a transition to more secure jobs; and more security for those who remain casuals.

The main planks of Labor’s policy, in addition to portable entitlements for casuals, are: extra powers for the Fair Work Commission to prevent exploitation in the “gig” economy; having “job security” inserted into the law; a crackdown on labour hire firms by writing the “same job, same pay” principle into the law; devising a new test to determine whether a worker is a casual; limits on fixed-term contracts; and a preference for government contracts going to firms offering secure work. Pivotal to this debate is whether insecure work is increasing. Albanese said one in four workers was a casual and the rate in hospitality had reached 80 per cent. During the pandemic, workers in casual jobs “lost their employment eight times faster than those in permanent jobs”, he said.

But Willox said: “The line that casuals are increasing is a myth. The fact is there is no explosion in casual workers. As of November 2020, there were 2.485 million casuals, 19.3 per cent of the workforce. That is down by 5 per cent from pre-pandemic levels. In February 2020, there were 2.624 million casuals, 20.1 per cent of the workforce.

“Apart from the major drop in the past 12 months, for the past 22 years the level of casual employment has been around 20 per cent of the total workforce or 25 per cent of employees in the workforce (if business owners and contractors are excluded)”.

Porter said: “The data is well known and telling. The percentage of people working as casuals is 25 per cent and has been for years. The percentage of people as independent contractors is 8-9 per cent and has been for the past 10 years. The notion that work is becoming more insecure is not borne out by any published statistics.”

Burke defended the foundation of the policy: “We’ve got to see insecure work as something bigger than casuals. Business says the proportion of casuals hasn’t changed over a period of time. But the number of people in insecure work has changed — while casualisation is the most traditional means, the gig economy is the new form. We also have work being structured through labour hire, outsourcing and by short-term end-to-end contracts.

“The overarching intention of our policy is to have more people in secure work. The gig economy will still be there but (it will be) more secure than it currently is.”

In reply, Willox said: “The digital economy has created completely new jobs and new markets. Despite being well under 1 per cent of the workforce, gig workers play an important role. Many businesses would not have survived the past 12 months without the services provided by gig businesses.”

With the debate looming on Porter’s IR reforms, Albanese said: “We have a fight ahead of us … a fierce contest to defeat the worst workplace changes since John Howard’s Work Choices, which were soundly rejected by the people more than a decade ago.”

Labor will oppose the bill outright in the second reading in the Senate. Those people demanding the Morrison government embrace far more aggressive economic reforms will have the validity of their arguments tested by the fate of the IR package.

Most of Porter’s package concerns incremental gains that will assist job creation. It defines casual employment and imposes obligations on employers to offer the transition from casual to permanent work. By altering award provisions, it encourages employees to work additional hours when it suits them. But the big deal is the effort to resurrect enterprise bargaining — which is the real test for the reform.

The enterprise agreement system is in crisis. The number of agreements has fallen from 25,000 in 2010 to 9800 in 2020. Porter says people on average get paid 40 per cent more on enterprise agreements than on awards. Reviving enterprise bargaining is pivotal to higher wages.

In negotiations with the crossbench, Porter can be expected to drop or modify the provision that has most upset the ACTU — saying that over the next two years, agreements making people worse off can be approved if in the public interest. Aside from this, the remaining efforts to revive enterprise bargaining focus on reduced complexity, faster approvals and remove the absurd hypothetical scenarios (about workers who do not exist) that have been used to deny agreements.

Under-pressure ALP leader Anthony Albanese has played the ultimately safe, traditional and highly political card — seeking to ensure the next election will produce the most pivotal Liberal-Labor split on industrial relations since Work Choices 15 years ago.