Labor offers big promise but no action on Defence

In what will one day be studied as the Platonic ideal of incoherent policy, the Albanese government has effectively decided to degrade and diminish Australia’s defence forces.

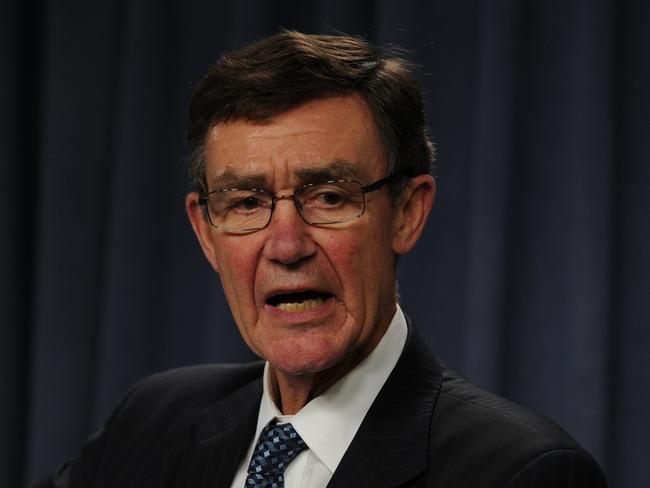

This is the only conclusion possible when you try to make sense of the tsunami of conflicting, confusing, conflated and ultimately almost comic numbers Defence Minister Richard Marles put out this week.

Launching the new National Defence Strategy and the 10-year Integrated Investment Program, Marles said: “History will judge us not by what we say but what we do.” Dead right. Problem is, he’s not doing anything.

Marles: “Let me tell you the centre of strategic policy is defence funding … You can only do if you fund.”

Churchillian words, yet Marles is planning to gravely weaken the Australian Defence Force over the next decade, especially the next four years. He talks like Dick Cheney but acts like Bernie Sanders, and in the short term will cut Defence’s real funding. He claims if the nation sticks to his plan, it will acquire a more powerful defence force in time. In fact, even in the unlikely event that this plan is fully implemented, it would be 15 to 20 years before we get a more powerful ADF.

This is evident when you interrogate the government’s densely confusing and mainly fictional figures.

But first, understand today’s world. There are five compelling reasons government should substantially increase defence spending immediately.

1. Strategic threat

We live under increasing and urgent strategic threat. The 2020 Defence Strategic Update said we no longer had a 10-year warning time for the emergence of grave strategic threat. Former chief of the defence force Angus Houston, who led the Defence Strategic Review, last year judged the strategic circumstances the worst of his lifetime. The new National Defence Strategy says they have deteriorated further in the past 12 months.

These conclusions aren’t difficult to reach. There’s war in Europe and the Middle East. America is stretched. US isolationism, on right and left, is on the rise. China, as Marles has remarked, is engaged in the greatest military build-up we’ve seen in peacetime. So, assuming the ADF has some effect on national security, the need for action is urgent.

2. Nuclear submarines

We are planning to buy nuclear-powered submarines. Every nation that has gone from conventional to nuclear-powered submarines has massively increased defence spending. The Albanese government is not planning any significant increase in defence spending across the entirety of its first two terms (assuming it wins a second term). Therefore it’s cannibalising and degrading other defence capabilities to begin paying for AUKUS subs.

3. Cost

The cost of high-end military technology, like medical technology, is consistently outstripping inflation. Modern military technology can do much more than earlier technology, but it costs more. The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, of which we have 72, costs exponentially more than the classic Hornets it replaces, which cost more than the Mirages they replaced, and so on.

4. Inflation

General inflation is crippling military purchasing power. Marcus Hellyer, perhaps Australia’s pre-eminent military budget analyst, now with Strategic Analysis Australia, points out the government has not fundamentally recast defence spending or acquisition. It still uses as its baseline the 2016 defence white paper. Hellyer observes that, apart from the nuclear-powered subs and new light frigates, it has simply amended slightly the white paper. This has mainly involved cutting capabilities. The 2016 calculations assumed normal historic inflation rate of about 2.5 per cent. We’ve had several years with inflation way above that. The government compensates Defence for exchange rate movements but not for inflation.

5. Personnel crisis

The personnel crisis means our very small defence force of about 57,000 is 4500 short of target. Often we can’t deploy particular frigates or air warfare destroyers because we don’t have enough technically qualified crew. Soldiers don’t care much about an idealised defence force in 20 years. If they work in helicopters and there are no helicopters, if they are sailing ships without weapons or that can’t even leave the dock, naturally they quit in large numbers.

All five factors mean any sane government would urgently increase defence spending. That doesn’t apply to the Albanese government. Peter Jennings, former deputy secretary of the Defence Department and for many years head of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, tells Inquirer: “It’s irrational, it’s illogical and it’s the best we’ll get from this government.”

Let’s interrogate the figures a bit. Marles proclaimed in stentorian tones that the Albanese government would provide $50.3bn extra defence capital investment over the decade. Yet across the forward estimates, the next four years, the government provides only $5.7bn of new money. So 90 per cent of the notional $50bn extra comes after the forward estimates.

Hellyer judges that $5.7bn won’t even compensate Defence for cumulative inflation since Covid. When Marles was asked this question at his press conference he sputtered and obfuscated and didn’t answer. It’s astonishing how often Marles seems not to be across detail, how easily he’s flummoxed if the question moves five degrees beyond the talking points.

It may seem mean to be sceptical of the government’s 10-year promises. But we must be guided by empirical evidence and historical experience.

First, there’s simple common sense. If the government is slashing and burning existing programs because it won’t fund defence today, what basis is there for faith in giant funding promises five or 10 years ahead? Look at the historical record of Labor governments, though the last Coalition government was also utterly dismal. In 2009, Labor under Kevin Rudd produced a defence white paper that said we must double the submarine fleet from six to 12 as soon as possible. There was a squad of other spending commitments, too.

Nothing happened on the subs. By the time Labor lost office in 2013, defence spending had declined to the lowest share of GDP since the 1930s. I recall a Labor defence minister in that period telling me the government was committed to an “average” annual increase in defence funding and the first big rise would come in year five, after the forward estimates. Sound familiar?

In 1986, under Bob Hawke, the estimable Paul Dibb wrote a seminal review that argued that to produce a credible defence of Australia, Defence needed 3 per cent of GDP. His review became the basis of a white paper the next year. Although Hawke was a fine prime minister, genuinely concerned with national security, and did produce significant new defence capabilities, defence spending never got anywhere near 3 per cent of GDP and the navy never reached the proportions outlined in the white paper.

So the idea a government won’t fund defence today but will massively fund it in five years is inherently ridiculous. Given, as Marles says, that what the government does is much more important than what it says, what has it actually done? Almost all Defence documents are impenetrable. Defence hates anyone to contest or scrutinise their many fantastic claims. Analysing the defence budget has thus been one of the most important functions of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

Last year, ASPI lost its three great analysts, Jennings, Hellyer and Michael Shoebridge. But it still produced a useful analysis of the 2023 Albanese defence budget. Let me quote ASPI: “The urgency of the demands upon Defence isn’t reflected in its short-term funding. The only increase in the Defence budget over the next three years is compensation for the increased cost of imported military equipment flowing from the fall in the value of the Australian dollar. Excluding this, the core funding of Defence (not including the Australian Signals Directorate) has actually been reduced at a time when unprecedented demands are being placed upon it. Between 2023-4 and 2025-6, Defence funding, excluding compensation for adverse foreign exchange movements, drops from $154bn to $152.5bn.”

The government hated that analysis. It may be why the government is now conducting an inquiry into government funding for strategic think tanks, otherwise known as the “get ASPI” inquiry.

The next forward estimates takes us out to the end of the second term of the Albanese government. So across two terms of Labor government we get a spending increase of a pitiful $5.7bn, a little over 2 per cent a year.

But rest assured, in the third Albanese government, yep, the third Albanese government, should there be such a thing, defence spending rises dramatically. Then, Marles says, it magically rises from 2 per cent of GDP to 2.4 per cent of GDP, though of course no one has the faintest idea what our GDP will be in 10 years.

Marles has adopted a truly bizarre, inexplicable intellectual framework. It goes like this. Australia’s strategic circumstances today are uniquely dangerous. We must act to secure our independence. We have to urgently pursue policies and write many reviews, which will begin to yield some capability in 10 years or more. Anyone who suggests it’s remotely possible to do anything significant before then “lacks wit” (a marvellous Marles locution, on a par with “impactful projection” and “profound transformation” as terms of baffling and vacuous endearment).

In fact there are many things we could do right now that wouldn’t adversely affect our aspirations in 10 and 20 years but would have nearly immediate effect.

One of the government’s worst decisions was to scrap long-established plans to buy a fourth squadron of F-35s. We have three squadrons, or 72, F35s. We have a squadron of 24 Super Hornets and 12 Growlers, electronic warfare fast jets. As Dibb remarked back in the 1980s, Defence always has about 100 fast jets. So in the piping days of peace 40 years ago, we apparently thought we could defend Australia with 100 fast jets, and we still think that’s the right number.

The government says it scrapped the fourth squadron of F-35s because if it bought them it would have to retire the Super Hornets. But there was another option for any government that took its faux-Churchillian rhetoric seriously: expand the air force by one squadron. Keep the Super Hornets and Growlers, but also get the fourth squadron of F-35s.

The F-35 is the world’s most advanced fifth-generation fighter aircraft, the backbone of the US Air Force and of allied nations such as Israel. It has a good range, longer with in-air refuellers, and can carry long-range missiles. As the Israelis have shown, it can shoot down missiles, something we need with the IIP shedding missile defence projects. It fits every possible main military task.

It’s obviously critical in the continental defence of Australia, should worst ever come to worst. It’s also vital in dominating our northern approaches. Because it’s perfectly interoperable with US forces, it could also be of use in any conflict in East Asia or Europe or the Middle East. We could send a squadron, or a part of a squadron, to join US operations in any theatre.

Because we are an intimate ally of the US, our F-35s are on the same technological improvement glide path the Americans provide for themselves. It’s just a matter of ordering another squadron. So naturally the government killed it.

The government has taken countless destructive decisions like this. It claims we’re going to double our surface fleet, some time in the 2040s perhaps. Yet we’ve ditched two supply ships. Here’s a trick – you can’t do “impactful projection” if you can’t supply the ships at sea.

We’ve scrapped the planned de-mining fleet. Yet de-mining is a critical military capability. If the Chinese are ever cross with us they could simply send down submarines or undersea drones and lay smart mines in all our ports. We couldn’t do anything about it. The government claims it will do de-mining with autonomous vessels. But this capability doesn’t yet exist. It’s a phantom. We’ve abolished a capability in favour of a fatuous press release.

As my colleague Ben Packham wrote, the government is effectively scrapping billions of dollars for previously committed programs on ballistic missile defence and medium-range air defence.

These were projects Australian industry was looking forward to participating in. Their fate demonstrates why you have to take government defence documents with a large chunk of scepticism. They were in the last Integrated Investment Program, not as maybes but as definites. Now, officially, they’ve been moved to the right on the time line.

Defence has three stages of killing a project: delay, salami slice – making the project ever smaller – and finally killing it. Most Defence projects that die first endure a long twilight of delay.

Australian defence is simultaneously hi-tech and antique. The whole world now is obsessed with the military power of drones, as we see in Ukraine and many other theatres. Even Iran’s drone attacks on Israel were militarily effective even though they were knocked out. They were much cheaper to produce than the missiles Israel used to destroy them. That’s classic asymmetric warfare.

We are apparently intellectually incapable of this. Although in the government’s confetti spray of figures there are billions of dollars allegedly devoted to drones, almost all this money is taken up in the Ghost Bat, a large and hugely expensive unmanned plane, not yet in service, and its underwater analog, the Ghost Shark, a large, expensive unmanned submarine, also not yet in service.

But the revolutionary innovation of cheap, swarming, deadly drones is apparently beneath us. Marles announced the truly pitiful sum of $1.1bn for such drones across the next decade. We have seen the future, it seems, but determinedly prefer the past.

Even the government’s critics are too kind to it. Countless analysts from all over the political spectrum point out the government is leaving us effectively defenceless for the next decade. The IIP has on page 11 a fascinating pie chart that shows 38 per cent of investment over the next decade is in maritime, more than air, land and cyber combined. That’s almost all nuclear submarines and Hunter-class frigates, which means almost nothing for anything else.

Over the next decade we’ll spend not far short of $100bn on nuclear submarines and the colossally wasteful Hunter frigates before we get one speck of capability out of them – $100bn for nothing over 10 years, there’s urgency for you.

But here’s the real trick: we don’t actually get a capable force after 10 years. Ten years from now we will still have a surface fleet the size of today’s surface fleet, at best. And if by some astonishing miracle we get the first Virginia-class submarine on time, we’ll have one nuclear-powered sub.

This is not a focused force or a balanced force, it’s almost no force. Even if against all experience this week’s plan is implemented, we won’t have a significant defence force at all for at least 15 years, probably 20.

The only thing the government has produced is reviews, reports, procrastination, capability cuts and delays. It says by the end of this year it will choose a design for a light frigate, a very minor war vessel, to replace the Anzacs. It could have done this in its first month in office, not going into its third year. The US and Japan want us to be part of a common air defence system, but we’re slashing funds for air defence. We could have ordered Patriot defence missiles in the government’s first week. Instead we’ll be lucky to order them any time in the next 10 years.

So we recognise a big problem in 2009, declare in 2020 we no longer have a warning period, and that our strategic circumstances are uniquely dangerous and further deteriorating, and our response is that, perhaps, by 2040 or 2045, we’ll have a stronger defence force.

That’s a nation gone crackers.

One interesting result of the week is that the opposition has committed to going to at least 2.4 per cent of GDP on defence within the decade. Peter Dutton confirmed to Inquirer that the Coalition would spend more than the Albanese government on defence, including going beyond 2.4 per cent of GDP. This position was first put by opposition defence spokesman Andrew Hastie, who was backed up by frontbench colleagues James Paterson and Simon Birmingham. Even a ropey long-term funding commitment is much better if it’s bipartisan.

But let me hasten to say the Liberals were utterly hopeless on defence during their time in office, droolingly, dreadfully hopeless. Defence is a colossal bipartisan failure, evidence of Australian misgovernment, short-termism, attention deficit disorder and a refusal to deal with reality. It’s consistent with the facts that perhaps the Albanese government never cared about defence but embraced the AUKUS rhetoric, and Marles’s hollow mock-Churchillian speeches, only to insulate itself politically on national security. But reality generally asserts itself. The latest polls show Labor now falling behind on national security again.

The politics don’t really matter. The absolute failure of the nation to take its own defence seriously matters a great deal, more than anything.

In what will one day be studied as the Platonic ideal of incoherent policy, the Albanese government has effectively decided to degrade and diminish Australia’s defence capability for at least the next decade.