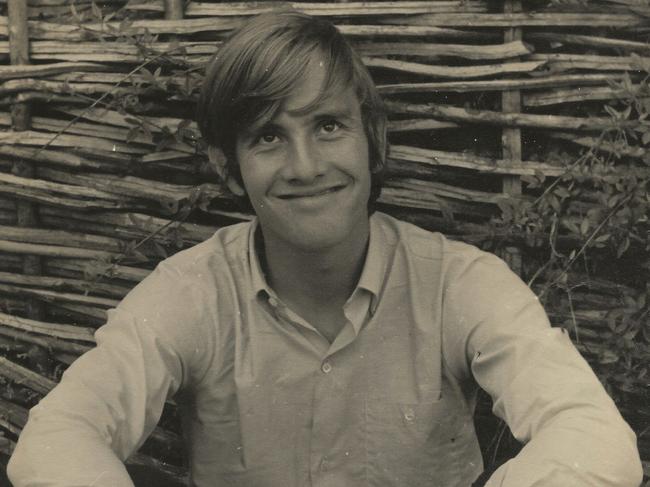

After three marriages and many flings, Oliver Freeman reflects on some hard-won lessons

Oliver Freeman, a man with three marriages and seven children, had a ‘rather long adolescence’ before making the link between his affairs and the collapse of his relationships. His book reflects on his life in a way he hopes ‘other men find useful’.

Oliver Freeman has seven children from three wives. His new book? It’s advice for men in “love relationships” and he’s is the first to say the obvious: “Wait … what does a man with multiple marriages have to offer?”

“The other obvious point is: who cares about me?” he adds, with a chuckle.

“I’m not a public figure. In fact, my first wife, Liz, when I showed her an early draft, said she wasn’t particularly unhappy with the book but she couldn’t quite see why I bothered to write it because who am I exactly?

“And I suppose the only thing I can say is, I’m at that stage in my life – I’m 81½ – where I can be honest about my life (three marriages, two “sustained” affairs, many, many flings) in a way that other men may find useful.”

Freeman is being a little modest there: he’s not exactly nobody in the book world. He had a 50-year career in publishing, serving as chairman of the Copyright Agency Limited and as vice-president of the Australian Publishers Association; he was also part of the London team that first published Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch.

“I was thinking about Germaine’s book when I started writing,” he says. “I was reflecting on how much the world has changed over the past 50 years”, and then the manuscript morphed “into how much I have changed over the same time period, and I thought, why not share a little of what I’ve learnt?”

And so to Freeman’s life: he was born prematurely on a cold Christmas Eve in England in 1943. He failed to thrive and was later diagnosed with an “eye wobble” that caused him to tip his head rather extravagantly to one side to see, which in turn made his tongue loll out.

He was labelled “mentally defective” on his medical records and for a time attended a preschool for “maladjusted and special children” (riding there on the bus, alone, from age five). Nonetheless, his parents, Frank and Pamela, didn’t mollycoddle him.

“I don’t doubt that they loved me,” he says, but like many British parents born in the first decade of the 1900s they didn’t hug him much either. Did that, perhaps, have something to do with Freeman’s long search, as an adult, for attention and affection?

“I’m sure it did,” he says. “I think I became very needy.”

There may have been some modelling going on, too: Freeman says his father was a womaniser and “a dreadful flirt”. He did not inherit the skill, saying he was “deeply perplexed at just how you went about asking a girl for a date”.

When a friend in high school set him up with a girl, he took her to the movies only to spend “the whole evening anguishing about putting an arm around her” without actually managing to do it. When the movie was over, she rushed to the bus and they never talked again.

Not a good start, then.

At 18, Freeman met a girl called Liz who was from a village one over from his own. Their courtship will be familiar to readers of Ian McEwan’s On Chesil Beach: they were smitten but shy virgins. They fumbled for a while and then found sex, when they had it, fraught with risk.

“We used luck, condoms, withdrawal and the Catholic methods” to avoid pregnancy, he writes, and pregnancy duly followed.

They were both 19. Their parents met for a conference over the dining room table and the couple was swiftly married, with their son, Tom, arriving in the customary less than nine months.

Freeman says his love for Liz, grounded in “a shared adolescence, a shared virginity, deep friendship and surprising parenthood” was not enough to keep him on the porch. This was the (literal) Swinging Sixties in London. Across the pond, John Updike was writing Couples.

Freeman had his first affair, with a woman called Julia, while still a student at Essex University. He wondered whether to leave Liz but decided to stay and they had two more children. He had started his career in publishing in London when famed publisher Sonny Mehta came in with Greer’s book.

“He threw it down … I think I was the fourth person in the world to read it,” Freeman says. “It was one of those moments rarely experienced by publishers … during my 50 years in publishing nothing compares to the impact.”

The book sparked a revolution in relations between the sexes, and Freeman began to wonder whether the mad desire for other women he was experiencing stemmed from never having “sowed the wild oats” before settling down.

“I decided to test it by taking the unusual step of sleeping around,” he writes. “This did not come naturally to me, but if all my problems were a lack of sexual experience (only three lovers as I approached 30) then maybe I should give it a go.

“Like a lot of pathetic males, I have always liked to be liked,” he adds.

Before long, his marriage to Liz had collapsed, mainly “under the urgent weight of my love affair with Gill” who worked in his office. After much agonising, he and Gill decided to set up home together, taking to the floor of a friend’s flat in Highbury “as we pushed out the boat on our relationship”.

The couple married, and had a child (Freeman’s fourth), but while visiting Toronto on business he fell in love with another woman called Valerie. The attraction was so powerful, he says, he was prepared to stand in the snow with a frozen beard while he waited for the plane to take him to see her.

Freeman moved to Australia in 1984, mainly so he could set up a local office of the Longman publishing group. Gill came with him, but Freeman says he had “betrayed her trust by fooling around with other women … and once she was aware of my dalliances, the contract was broken”.

“She wanted absolute loyalty from her partner, and I let her down,” he writes. “My behaviour was dishonest … and as it turns out, destructive.”

Because Gill soon found a new love of her own and left him. He was heartbroken, yet he still couldn’t seem to grasp the problem, which was his own failure to make a link between his affairs and the collapse of his relationships. For example, he remembers being offended when a friend described his decision to hop into somebody else’s bed at the famed Frankfurt Book Fair as “cheating”.

It was a “casual one-nighter … regrettable, stupid, thoughtless” – but cheating?

He can see now that he was constantly thinking only of himself: if you can get away with it, don’t worry, and it’s not like everyone else isn’t doing it, so what’s the harm? (Not that it was always harmless; Freeman says he once called out his lover’s name while in bed with his wife, which went down as brilliantly as you might imagine.)

He also couldn’t grasp the damage adultery was doing not only to his relationships but to also to himself.

He was depriving himself of real intimacy in his marriages by breaking the bonds of trust. He simply could not see that the deception necessary to conduct the affairs was fatal to intimacy. Only now can he see that the impact of his affairs on his marriages was “catastrophic”. How did the realisation come?

Well, two weeks after Gill left him, Freeman met his current wife, Susie Brew. They dated for a while before moving into an apartment near Sydney Harbour Bridge, with “funnel webs and termites”. He says Susie insists on the importance of fidelity and (amazingly, given his CV) also trusted him to do the right thing.

Around the same time, he remembers talking to his oldest boy, who was (and is) in a committed relationship with a childhood sweetheart.

“I wanted to advise him to perhaps ‘play the field’ before he settled down because I hadn’t done that and look how things worked out for me,” he says. But his son said, “No, Dad, it’s fine, because I’m not just in love with her, she’s also my best friend.”

He has replayed that conversation over in his head a million times.

His son had “gotten in a trice” what it had taken him a quarter of a century to discover: that intimacy isn’t about romantic love or desire for another person. It’s “the territory you occupy after you’ve made love, the terrain beyond sex. Real intimacy is a special place, and that special place cannot be destroyed, unless you’re extremely foolish. Lying and denial are lethal. If you get to that special place, which I have, you want to preserve it at all costs.”

This is, of course, precisely what the church has been teaching for 2000 years. Freeman accepts that he perhaps had a “rather long adolescence, but the 20-year period I’m writing about, from when I was 20 to when I was 40, coincided with huge changes for the whole world in terms of attitudes to relationships, between men and women, and what I’ve decided to share is what I learnt over that period of great change”.

Having finished his book, he contracted an agent but he couldn’t place it. “I did try one or two bigger publishers, but one of the responses I got was, roughly, we don’t need Oliver Freeman mansplaining issues relating to sex, love and marriage to us.

“And fair enough. Although, when you receive a communication like that, you feel that you’re somehow being censored, when I think it’s important for all points of views to be up for discussion.”

As for what Freeman’s wives think of his decision to let it all hang out – these are private matters, after all – he says he sent the manuscript to all three wives before he published it, and while some made small changes, they accepted the book.

Freeman’s third marriage is now in its fourth decade. He and Susie have three children together, and while they do bicker, of course, it’s mainly over “small things” like his “mildly obsessive” habit of collecting things. He has 3500 books, plus 1000 CDs, plus a collection of green plates, plus many clocks, and many more fob watches.

If that were not bad enough, towards the end of his book Freeman confesses to a habit so awful it’s astounding that anyone would be willing to turn a blind eye to it. Flamingos. He’s obsessed. He got his first one on a shirt from Lowes in Woy Woy. He has since expanded his collection into statues, and figurines.

Susie is a minimalist. She doesn’t want a flamingo collection, yet she’s hanging in there. If that’s not love, what is?

Intimacy: Men and Their Love Relationships by Oliver Freeman, with foreword by Wendy McCarthy, will be published by Ginninderra Press on April 9.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout