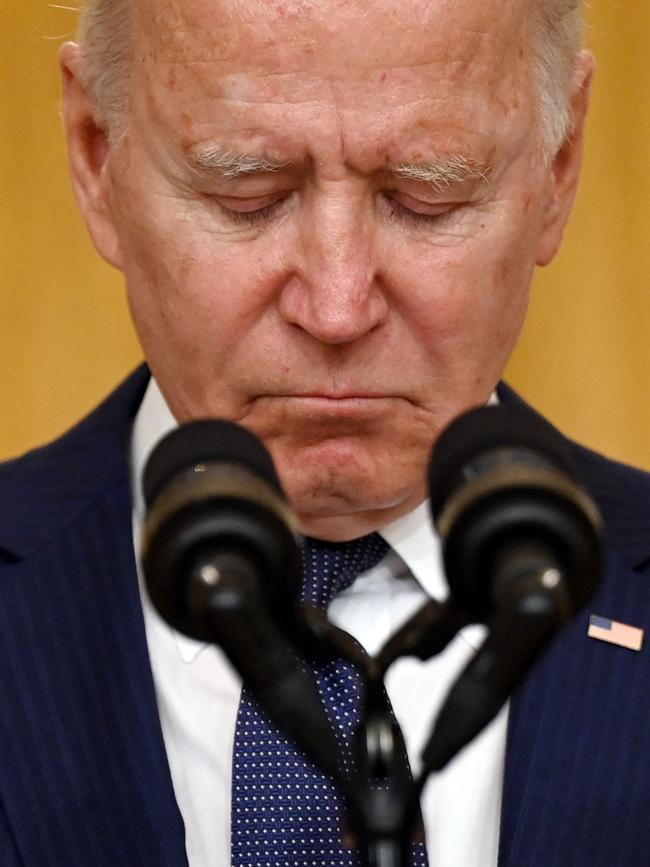

After four painful years with Donald Trump at the helm, Joe Biden’s ascent to the presidency was a welcome relief for America’s foreign policy establishment.

Trump’s erratic posturing became Biden’s avuncular restraint. “America First” became the more reassuring “America is Back”.

Here was a man with deep foreign policy experience, honed over years in the congress and the White House – likeable, measured and steeped in the ideal of US global leadership.

He was an internationalist, a supporter of the international agencies and forums that sustain the foreign policy bureaucracy. Yet not even a year into his presidency his reputation is in tatters, assailed from all sides for pulling the trigger on a withdrawal from Afghanistan that even the President’s allies admit was disastrous.

Robert Gates, a former US Defence Secretary under both George W. Bush and Barack Obama, in 2014 uncharitably said Biden had been “wrong on nearly every major foreign policy and national security issue over the past four decades”.

“The Biden doctrine is like the Trump doctrine except worse,” says Ryan Crocker, who served as US ambassador to Iraq and Pakistan under both Bush and Obama. “Frankly, I have serious questions about his competency.”

James Cunningham, US ambassador to Afghanistan under Obama and who voted for Biden, says the President has “trashed” the US’s reputation.

“For our competitors, it’s been a gift: the Chinese, the Russians are out there saying Americans can’t be trusted, they are only out there for themselves,” he adds.

Biden’s popularity fell sharply in late August after the withdrawal, his disapproval nudging above his approval rating for the first time on August 29.

The debacle threatens to distract, and potentially derail, his domestic “Build Back Better” agenda, hinging on infrastructure, education and social security, as moderate Democrats in congress, a handful of whom hold the balance of power, distance themselves from the public face of the humiliation.

The cacophony of criticism makes the withdrawal seem like the defining moment, and failure, of the Biden administration. It’s left pundits puzzled as to what Joe Biden stands for abroad. How is America “back”, as the President enthusiastically told world leaders at the G7 summit in June, if it’s retreating?

“We simply don’t understand how all this will affect Biden’s perspective,” says Andrew Basevic, a historian of American foreign policy at Boston University.

“But as distributing as events of the last couple of weeks have been, they matter much, much less than the previous 20 years: I mean, what the hell were we trying to do?” he asks.

Indeed, history may well have a different view of the past few weeks. Technically, the mad scramble was a logistical triumph, airlifting more than 120,000 people from Kabul in 17 days.

Traumatic scenes of Afghans trying to board US planes as they took off, some falling to their deaths, reflected the reality of a rushed evacuation. The murder of 13 Americans and hundreds of Afghans at the hands of ISIS-K suicide bombers will forever cast a pall over the withdrawal.

Expecting zero military and civilian casualties from an operation of such a scale and speed was asking too much.

MORE: Adam Creighton explores Joe Biden's America

Pejorative comparisons with the US evacuation of Saigon in 1975, ending the Vietnam War, with similarly desperate scenes, miss the point. That evacuation, Operation Frequent Wind, which saw a relatively few 7000 people evacuated by helicopter from Saigon rooftops, was and is considered a major success.

In fact, for ordinary Afghans, the immediate collapse of the previous Afghan regime, which had been propped up by the US, was the best outcome given a Taliban takeover was inevitable.

Thousands of soldiers, and even more innocent Afghans, could have pointlessly died had the previous government of Ashraf Ghani put up a fight.

With up to 200 Americans still in the country, the grim prospect of a hostage crisis, reminiscent of Tehran in 1979, remains. But it’s hard to blame Biden.

As Secretary of State Antony Blinken said on Friday, the US government had since March sent 19 separate notices to American citizens in Afghanistan encouraging and then urging them to leave. For weeks before the evacuation began on August 14, the US had offered to pay the flights out for Americans.

Moreover, the Afghan government insisted the US not conduct large-scale evacuation lest it trigger a loss of confidence in a government the US spent 20 years and trillions of dollars building.

Fault mainly lies with US intelligence. It believed the Afghan government and military could withstand the Taliban for months, perhaps years.

Americans are with Biden on this issue too.

John Pitney, a professor of political science at Claremont McKenna College, who’s long tracked American’s attitudes to foreign affairs, says the short-term hit to Biden will evaporate. “Americans, to put it bluntly, don’t care much about foreign policy,” he says.

“If there were a terror attack here or a hostage crisis, sure, things would be different, but right now most Americans have mentally checked out of Afghanistan,” he adds.

Even against a backdrop of terrorist attacks and a deluge of negative press, still 54 per cent of American voters said the decision to withdraw troops was right, according to the Pew Research Centre. In 2019, almost 60 per cent of veterans said the war wasn’t worth fighting.

Not even 1 per cent of Americans nominated Afghanistan, or foreign policy more broadly, as their most important issue, according to a long-running Gallup poll conducted during the withdrawal.

“I’m quite struck by the crescendo of criticism; my best guess is that with passage of time and advantage of hindsight, Biden’s tough decisions will look pretty good,” says Charles Kupchan, a senior fellow at the Council of Foreign Relations, offering a rare fragment of support.

Historical comparisons are fraught, but Ronald Reagan was easily re-elected after terrorists killed hundreds of US and French servicemen in Beirut in 1983, fuelling doubt about the judgment of the then first-term president.

The 18 Americans killed when two Blackhawk helicopters were shot down in 1994 in Somalia, prompting the resignation of the then defence secretary, were a political hiccup for Bill Clinton, who was even more popular in this second term.

Jeff Gunn, a security analyst at a computer software firm in Maine, is as far outside the Beltway as you can get.

“It’s too easy for people to look at the situation and use it as another way to criticise an administration they don’t agree with for other reasons,” he adds. “Biden made a commitment to get all troops out by end of month, and I don’t know how Republicans can say for sure that they would have done much better,” he tells The Australian.

Republicans and conservative media have made much of Biden’s perceived blunder, even though Trump had planned to withdraw by May, had he been re-elected.

The Afghanistan withdrawal shouldn’t have been a surprise. Biden was pessimistic about the US mission even before being sworn in as vice-president in 2009. He famously stormed out of a dinner in Kabul with former president Hamid Karzai in 2008, frustrated by the leader’s denial of rampant corruption.

“Any presidential candidate would say they were going to withdraw, they have for 20 years; but I didn’t put any more weight on it at the time,” says Crocker, referring to Biden’s promise to leave Afghanistan in the run-up to the 2020 presidential election.

If courage is creditable, the President scores highly for standing up to the military-industrial complex, a force former president Eisenhower warned about 60 years ago.

Trump’s America First slogan, however much it grated, reflected a timeless truth. The interests of the ordinary Americans loosely align with those at the top.

“In great empires the people who live in the capital, and in the provinces remote from the scene of action, feel, many of them scarce any inconveniency from the war; but enjoy, at their ease, the amusement of reading in the newspapers the exploits of their own fleets and armies,” wrote Adam Smith in 1776, just as the US was severing its ties with the Old World.

“To them this amusement compensates the small difference between the taxes which they pay on account of the war, and those which they had been accustomed to pay in time of peace. They are commonly dissatisfied with the return of peace, which puts an end to their amusement,” Smith went on.

When the central bank is printing the money to help pay for the wars, even better.

Every two years the people in the capital, at the White House, Republican or Democrat, produce a National Security Strategy, laying out the priorities and philosophy of the US government abroad. Trump’s, published in late 2017, didn’t carry much weight because its author, national security adviser Herbert Raymond McMaster, was fired soon after.

“Biden brought in the A team, all of them people those in my line of work know very well,” says Crocker, referring to the urbane Blinken, and prodigious National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan, who’s overseeing the drafting of the new strategy.

The interim report, released in March, describes a historical “inflection point”, one of the President’s favourite phrases, where autocracies have started to threaten the pre-eminence of democracies for the first time since World War II.

“We are in the midst of a historic and fundamental debate about the future direction of our world,” the President wrote.

“China is the only competitor potentially capable of combining its economic, diplomatic, military and technological power to mount a sustained challenge to a stable and open international system,” it says, promising to “support Taiwan … in line with longstanding American commitments.”

Stripping back the cant, the document advocates rejuvenating traditional alliances with Europe, Australia and Japan, to present a united front to China, Russia, Iran and North Korea. It wants the US to lead the world’s response to Covid-19 and climate change. Indeed climate change features 27 times across 24 pages. Trump’s 68-page national security strategy mentioned it four times.

Economic reality overshadows whatever grandiose documents the bureaucracy produces, however. The US is in relative decline, exacerbated by a domestic spending binge.

The President is planning spending of $5 trillion on domestic infrastructure over the next decade, inevitably leaving fewer funds for weapons and soldiers

As Biden shifts the US toward a European-style welfare state, the military will become less affordable.

Washington’s debt is at the highest level since World War II, and health and social security costs will balloon as the population ages.

The US has spent $US2.3 trillion on Afghanistan over 20 years, excluding the healthcare costs of looking after the veterans, according to researchers at Brown University. By 2050, veterans of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars will cost another $US2 trillion.

Europe relies on the US for its security because its giant bureaucracies and social welfare systems have brought taxation to its practical limit.

Along with economic reality, US foreign policy is moulded by the personality of the commander in chief. Biden’s foreign policy resembles Trump’s, in substance and even style, more than it might appear.

“Trump was the first American president who tried to break context that had governed US foreign policy since World War II, it was a very consequential thing, and the trend hasn’t been extinguished,” says Cunningham, now a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council.

“In one fell swoop in April, without any meaningful consultation with allies, he reopened the perspective that Americans were on their own,” he adds, referring to Biden’s announcement of the August withdrawal deadline.

Assuring his counterpart in Afghanistan, Hamdullah Mohib, of unwavering US support was Jack Sullivan’s first act as National Security Adviser last January.

Then days later, new Secretary of State Blinken, presumably on instruction, sent a note to the Afghan president. “It was basically hostile in tone, and in the arcane world of diplomacy foreign ministers do not write letters to heads of state; it’s an insult,” Crocker, a diplomatic in residence at Princeton University, says.

Biden, 79 in November, is unlikely to run again. If the Democrats lose control of congress next year, making domestic policymaking all but impossible, the Afghanistan withdrawal may be the defining feature of his presidency.

Unless the US suffers some horrific terrorist attack linked to the Taliban regime, it will be seen as a virtue. History doesn’t care about the minutiae of withdrawals or contemporary political fashion.

Biden might have got a lot wrong over 40 years, but so too has the foreign policy establishment, from Vietnam and the Bay of Pigs, to Iraq and Libya more recently.

In Afghanistan, Biden got the big call right, even if he didn’t bother picking up the phone to call Scott Morrison. “I assumed it would have been one of his first calls,” Crocker says, shocked the President took so long, almost three weeks, to call the Australian PM after the withdrawal began.

Biden’s personal regard for Morrison to one side, the US withdrawal isn’t a sign the US won’t defend Taiwan should China try to retake the island.

It may even make the US more assertive of democracy’s rights.

Husain Haqqani, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute and former Pakistan ambassador to the US, recalls a conversation in 1983 with a senior US official after the sudden US invasion of Grenada, an unimportant Caribbean island nation in which the US has taken little interest, before or since.

“Why would you want to invade Grenada, I said to him, and he was quite clear it was to show the world the US could still flex its muscles after the humiliation of the Iranian hostage crisis,” he says.

The embarrassment of Afghanistan, far from reflecting a declining willingness to protect allies, could make the US more determined to support genuine democracies.