Adapting to uncertainty can conjure a new sense of order

On each turn on the pandemic road, hopes have proved illusory. How much longer can we live like this?

Round each turn on the Covid road – and the number of turns ever multiplies like a cancer – the view ahead glistens with hope. The hope is of predictability, of a timetable, of a plan that can be trusted to work – in short, confidence about the end of uncertainty. The need for order is primary among humans. With pandemic, as with war, minds can easily become obsessed with the fantasy, fed by anxiety, of an end in sight. When there is no end in sight, recurring panic attacks may follow.

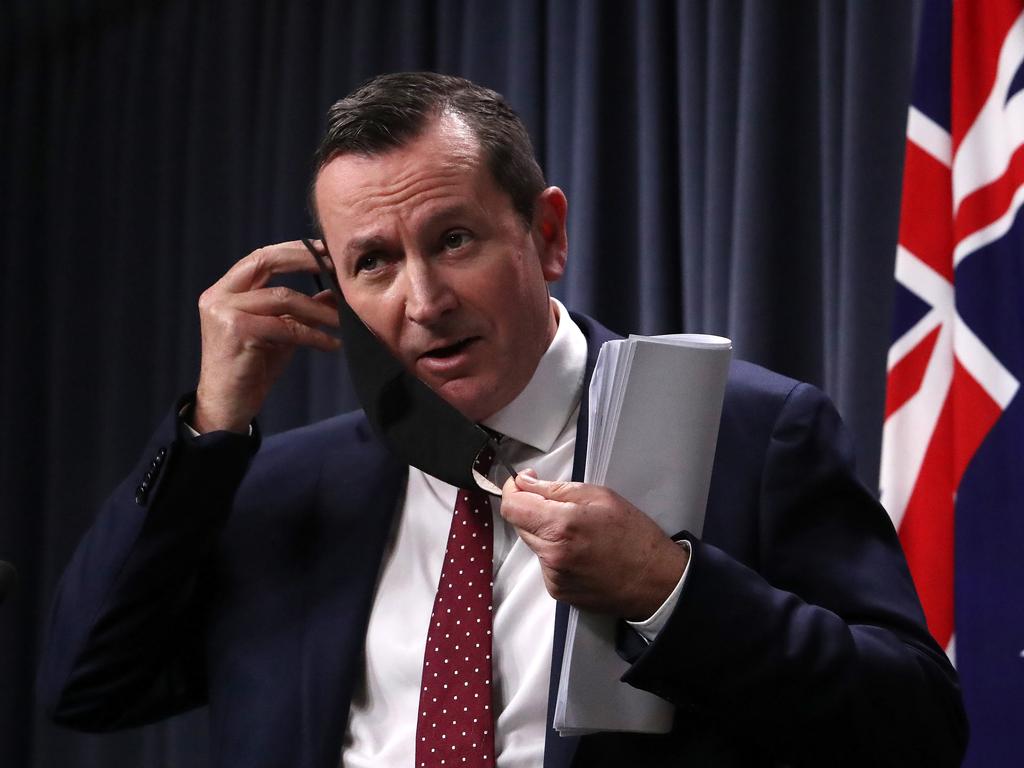

Australia has just plunged into a new phase of formless free-floating panic – at the sheer uncertainty that faces us. It may be glimpsed in the faces of state and federal political leaders, and in their tone. The fear is starting to grow that there may be no end in sight. And who knows what levels of unease, and worse, are rising behind closed suburban doors across the eastern states, with the streets ominously empty once again.

On each turn on the pandemic road so far, hopes have proved illusory. Covid-19 is staying true to type – a slippery elusive monster that almost seems to delight in outwitting us humans, in mockery of our pride in scientific reason and technological ingenuity. Hope so far has fizzled out every time, in decisive rebuff.

The latest turn has been the hope for vaccine salvation. 2020 became focused on a vaccine being available by the end of the year, a vaccine that would quickly negate the virus threat. Now, eight months into 2021, and with majority populations vaccinated in a handful of countries, a new wave of uncertainty threatens. Israel, Singapore and Holland have opened up only to see rapid acceleration in infection numbers, followed by a growing threat to hospitals, forcing those countries to reimpose restrictions. The same is happening across the United States – Florida hospitals are full. Britain is being watched around the world with fascination, as it tries the same perilous experiment of staring down the virus monster, challenging it do its worst as the public begins to socialise freely.

A further dimension of uncertainty has been added with the Delta variant. The young who were, with earlier strains, seen to be relatively safe from the virus are now vulnerable. More are needing hospitalisation, some intensive care. And, serious for the longer term, the young are becoming prime carriers.

Learning to live with Covid, the futuristic sci-fi devil that became manifest, is tortuously difficult. Given future unknowns, it is not even clear what, in reality, the bleakest scenario might entail. Some degree of herd immunity will come. But even that is ambiguous. Many assume that once a person is vaccinated, they are safe. Multiply that up to 80 per cent of a total population then the virus is contained.

But a person vaccinated against, say, measles is more likely to catch measles in an unvaccinated population than an unvaccinated person in a predominantly vaccinated population. This means, to take the critical case, that an unvaccinated population of schoolchildren may become the next frontier of Covid infection, that is whenever most adults have been vaccinated. Combating the Delta variant in the short to medium term may necessitate home schooling becoming the norm rather than the exception.

Above all, what will come to constitute a tolerable level of herd immunity is likely to be a complex sum of vaccination patterns and sequences through all age groups, in combination with other types of immunity. This complex, viewed from today’s standpoint, is a perplexing unknown.

Many claim their rights are being infringed and that governments are cavalierly increasing their powers under the cloak of emergency. Surely, in answer, the liberal principle remains supreme: that individuals should be free to do whatever they choose unless their act harms others. Lockdown does curtail individual freedoms but does so in order to limit the widespread social harm of illness and death. Likewise, mass vaccination is justified in enabling herd immunity which will, in the end, work for the greater good.

One sign of the generalised social panic in the air is the flight by normally rational people to social media sites spreading sensationalist untruths about Covid and its prevention.

It is less clear how coercive a society should become in punishing the tens of thousands who flout prudent law to attend anti-lockdown demonstrations, or in enforcing vaccination among those who resist. In the end, how many of the hesitant get vaccinated will depend on social cohesion. The collective conscience proved strong in Victoria last year, reflected in high acceptance of lockdowns, and compliance, so I think we can be confident that 80 per cent of Australians will agree to vaccination. Science, smart management and common sense have proved our best tools in the current war. Victoria has handled its recent Covid outbreaks much better than in the past because of efficient QR codes, faster and higher volume contact tracing and testing, and a more refined quarantining system – it has learnt from past mistakes. It is only fair to acknowledge this, especially by those many commentators, including myself, who were critical of the Andrews government and its shambolic Health Department last year.

And, as a nation, we have benefited from the federation structure. It has been vindicated in this pandemic, with management functioning more efficiently on a smaller, more local scale, decentralised down to the states. Differences of opinion among the premiers have actually helped the public debate about alternative strategies in defending against Covid.

Science is not infallible. With pandemic anxiety triggering a rush to spurious certainty, it has itself shown irrationalities. ATAGI, in cutting back its AstraZeneca recommendation to those over 60 – the AZ vaccine which saved Britain – showed a bewildering inability to weigh up risk probabilities of vaccine versus infection. It behaved like a timid bureaucracy with no big picture vision.

Also, furious epidemiological modelling is proceeding to plot possible future infection paths and rates, with the federal government currently pinning some policy hopes on the results. Good luck with that! Mathematical modelling was used last year in the long Victorian lockdown with spectacular irrelevancy.

The greatest uncertainty of all, one that faces the entire globe, is the fear of virus mutation into a variant resistant to current vaccines – Professor Peter Doherty has recently voiced just such a worry. The mega-spread of Covid internationally brings significant threat of mutation. If so, what will follow Delta? And then, what will the delays be in discovering and producing new effective vaccines. Even with Delta, Israeli statistics are showing the Pfizer vaccine less effective in limiting its spread. And on, and on, cycling out into the distant future, magnifying uncertainty.

There have been modest positives. After 18 months of sparring with the virus, grandstanding commentary has become wearisome. We still hear cries of outrage about lockdowns, and their excessive limits on individual freedom, business viability, children’s education, and mental health. But we know, faced with the slippery virus monster, as surely now as night follows day that there is no alternative to lockdown. Those distressed may storm up and down, stamp the feet, even cry out, but they need to grit their teeth and accept what is.

We also know that political decision-making has been devilishly difficult. Perhaps the main Melbourne lockdown last year went longer than necessary, and Victoria would have been better off then with the softer touch of the NSW Premier.

Almost certainly, Sydney would have been better off currently with the firmer hand of Daniel Andrews at the wheel, with his more authoritarian go-hard, go-early disposition. Indeed, Gladys Berejiklian’s soft touch has turned into dithering – globally proven to be disastrous with Covid. On a third front, the federal government was forced last year into rushed juggling of different vaccine options and was unlucky. Probably, it should have moved with greater urgency on Pfizer this year, and its messaging has been haphazard and poor. The Prime Minister himself, understandably eager to provide a timetable, has valiant hopes that the country will be 70 per cent vaccinated by the end of the year. Whether or not he achieves that goal, the leading truth about government in this country, in these pandemic times, is the old cliche that it’s easy to be wise after the event.

Sydney has no foreseeable end to its current lockdown, one which could well extend for months. It might come to learn, as Melbourne might have last year, from Joseph Conrad’s allegory of life suddenly stopped in its tracks. In his novella The Shadow Line, a young captain finds purpose in life as he takes command of a sailing ship in Bangkok. But all his eager ambition is thwarted by a lack of wind. He just manages to get the ship out to sea, precipitated by his own restlessness and the tropical fever that is spreading among his crew. Becalmed for an interminable 14 days adrift in cloying tropical heat, the atmosphere on board becomes fetid, with the chief mate going mad and all the crew, apart from one, falling sick and becoming useless.

Conrad draws the conclusion that in such a state of personal and social stagnation everybody should enter into a searching intimacy with their own self. To learn not to be faint-hearted. To be able to stand up to bad luck, mistakes, and their own conscience. Face-to-face with themselves and their fate, the recommendation is for realism, honesty and resilience, if the person has it in them. Life becalmed in shutdown, long or short, with the outside bleak and motionless, and new opportunity and hope closed off, the future unknown, may require its own searching intimacy with the self. And a long patience. We are at a point with Covid of having to live with uncertainty – a social state without precedent over the last eighty years. It is now futile to behave like the nervous traveller, who has eyes only on the destination. Or the obsessive person, wanting to chart the steps on the life path, in order to tick them off one by one, as if that is living. Such devotion to fruitless, abstract planning can only aggravate incipient psychopathology. Wise advice today might rather suggest: enjoy the journey as best as you can, make the most of it, unlike the bushwalkers whose minds are so focused on the mountain peak ahead they forget to take in the view along the way. In any case, our peak keeps disappearing from view and shifting.

The craving for order and certainty is strange in a species troubled by its own mortality, troubled to the degree that all its religions focus on finding a meaning for death, that there be more to it than dust and ashes. With death, that one ultimate and inescapable human necessity, the timing is usually quite uncertain. Further, to know in advance when the grim reaper will finally strike would be a curse that could well paralyse the life. Much better to live blithely, in ignorance. In this domain, uncertainty is a blessing.

Of course, the fact that Covid-19 triggers fears of acute illness and death changes things. It threatens to bring forward the final date, lifting the saving veil of uncertainty. So, a kind of metaphysical equation is scripted, in hope: predictability and safety in the foreseeable future, that is certainty now, in order to protect the nature and timing of the unforeseeable final departure, including its mystery. The pandemic continues to scoff at all such equations. We seem mere playthings in a new normal, one in which uncertainty prevails and Covid is master.

John Carroll is professor emeritus of sociology at La Trobe University.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout