Aboriginal access to polls at risk

The government’s cynical pursuit of voter ID laws will disenfranchise First Nation voters.

The Morrison government agreed in the last week of 2021 parliamentary sittings not to proceed before the coming election with its legislation requiring citizens to produce identification to vote.

But, given that he is anxious to appease the ultra-conservative rump that persists in promoting this legislation, Morrison will certainly revive the legislation if he is re-elected. In fact, only hours after the government agreed to postpone the bill, Liberal senator James McGrath, who chairs the Parliamentary Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, told the Senate that voter ID was “essential to fair and open elections”.

Pitching this bill as somehow promoting integrity, as its title suggests, is dishonest. The very title, Electoral Legislation Amendment (Voter Integrity) Bill 2021, offends me because the arguments used to advance the legislation are completely lacking integrity.

The Liberal Party has had an obsession about voter ID for years. The past three federal elections have delivered Coalition governments, which has given the Coalition majority membership of the committee on electoral matters, which reports on the conduct of each federal election.

Three times now, after the 2013, the 2016 and the 2019 elections, the Coalition majority has recommended the introduction of voter ID; each time Labor has opposed the recommendation.

So why has the government been so hellbent in pushing for legislation this third time around? I’d venture a few reasons:

First, those from the far right in Australia have become more rabid during the past decade and more enamoured of the voter-suppression agendas that have flourished in the US.

Second, Scott Morrison has cynically sought to give succour to those on the far right to shore up his prime ministership.

Third, it’s my suspicion that the government has calculated there’s electoral advantage in requiring ID at the polling booth.

Given that there’s wide acceptance that First Nations voters will be particularly disadvantaged by voter ID, and that the government fears their votes might favour Labor, the Coalition stands to benefit in a seat such as Lingiari in the Northern Territory, where there’s a heavy weighting of First Nations electors.

Such calculation no doubt underlaid John Howard’s instruction, immediately after he became prime minister in 1996, that the independent Australian Electoral Commission disband the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Election Education and Information Service. The service had done great work to improve enrolment and voting of First Nations people, especially in remote areas (those rates are still shockingly low).

It’s not passed my notice that Ben Morton, the Special Minister of State who has carriage of this legislation, is a former director of the West Australian branch of the Liberal Party, which has form in the dark arts of voter suppression among First Nations people.

Morton would not remember a notorious incident in my home state more than 40 years ago, but I’ll never forget what happened at the WA election in 1977, when voting was not compulsory for Aboriginal people, and the Liberal Party became concerned when Labor signed up hundreds of new Aboriginal voters to the Kimberley roll.

Liberal sitting member Alan Ridge was rattled and later wrote to a supporter: “It was a degrading experience to have to campaign amongst the Aborigines to the extent that I did and it offended me to know that whilst I was concentrating my efforts on these simple people over the last couple of weeks, I was neglecting a more informed and intelligent section of the community … It is indeed a travesty of justice that a comparative handful of such ill-informed people … should have the right or the power to determine the future of our state.”

Fearing the newly enrolled electors might be inclined to vote for Labor, the Liberal Party parachuted a five-man team of lawyers from Perth into Kimberley polling booths on election day. Acting as scrutineers, they intimidated Aboriginal voters and stood over presiding officers at polling booths.

Their behaviour, and the failure of Electoral Commission staff to properly accommodate Aboriginal voters, caused enough votes to be lost to Labor that a Court of Disputed Returns voided the election.

The Labor candidate, Ernie Bridge, lost again at a new election, but was finally successful in 1980 – despite further crude shenanigans by Liberal supporters who delivered a 200-litre drum of port to the Aboriginal community at Warnum (Turkey Creek), in an atrocious attempt to get Aboriginal voters too drunk to vote.

In a letter on November 23 to parliament’s Joint Committee on Human Rights (of which I’m a member), Morton said his bill “aims to reduce the potential for voter fraud and impersonation, and safeguard public confidence in the outcome and integrity of federal elections and referendums”. But he failed to acknowledge the evidence of Tom Rogers, the Australian Electoral Commissioner, to a Senate estimates hearing in March that multiple voting was “a vanishingly small problem”.

Stressing that the AEC does not have a policy position on voter ID because “there are political dimensions to it”, Rogers said: “The vast majority of alleged multiple marks or multiple voting is for people over the age of 90 or people who have English as a second language or who are confused about the act of voting.”

As the human rights committee noted, it’s not clear that this bill would deter most instances of multiple voting because that small set of confused voters could simply show their same ID on multiple occasions. For the same reason, it would not reduce the risk of electoral fraud in the form of voter impersonation.

The committee reported in November that it’s not possible to conclude, as the state is required to demonstrate, that this bill addresses a pressing or substantial public or social concern. Further, the committee highlighted a risk that voter ID would impermissibly limit the right to participate in public affairs and the right to equality and non-discrimination.

Importantly from my perspective, the committee recognised the disproportionate impact that the bill will have on First Nations electors in remote communities (and on other vulnerable groups such as the homeless and women fleeing domestic violence).

Aboriginal people have no trouble understanding their own identity, knowing who they are and how and where they fit in. They have a special sense of family and a special knowledge of their place in their wider society, but too many have trouble proving their identity in the world of bureaucracy and administrative accountability. Not only do some born in the bush not have a birth certificate, they don’t have the language skills or ready access to officialdom to enable them to obtain the documentation that would satisfy the requirements of this proposed legislation.

It’s not good enough, as the minister has argued, that a voter who can’t produce satisfactory identification documents has the option of casting a declaration vote. In that case, the voter would still have to provide their full name, date of birth, a current address and a contact number. But, as the human rights committee has noted, it remains unclear how a person can complete a declaration form if they have no current address.

Further, the form also requires additional information such as a driver’s licence or passport number. The minister asserts that this additional evidence is wholly optional, but the committee has observed that the form doesn’t specify that, and that electors may not always understand the optional nature of this – if indeed it is optional. Anyway, just imagine how all this rigmarole would bog down Electoral Commission staff on election day.

Labor members of the committee on electoral matters made plain their position on voter ID when the committee reported a year ago on the conduct of the 2019 election. In a dissenting report, Labor members said a requirement to provide ID might have the effect of discouraging some people from voting and, in turn, undermining our system of compulsory voting. Not that those on the hard right would lament the dispatch of compulsory voting. Let’s not forget that forces in the Liberal Party, led by senator Nick Minchin, tried repeatedly in the 1990s to do away with compulsory voting. That, too, would have meant a diminution of the votes of First Nations electors.

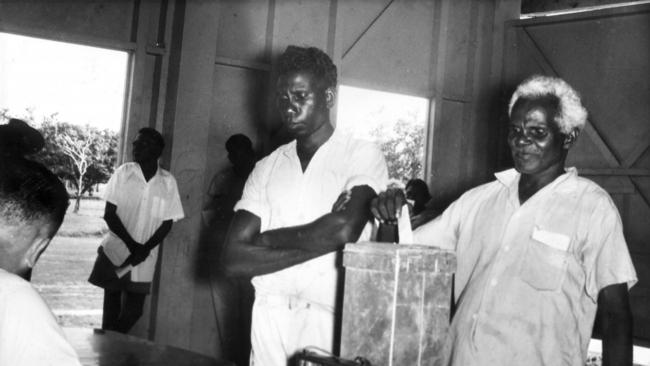

The tragedy of this latest attempt to suppress our voter base is that it took so long for First Nations people to achieve the right to vote in the first place.

We were excluded from the start. Historian Judith Brett has written that “the disenfranchisement of Aboriginal people by the 1902 Franchise Act is one of the infamous stepping stones of cruelty and shame in our treatment of Indigenous Australians”.

Aboriginal people did not begin to get commonwealth voting rights until World War II, and then it was limited to a temporary franchise for Aboriginal members of the armed services.

It was not until 1962 that the Commonwealth Electoral Act granted all First Nations people the right to vote – but even then enrolment wasn’t compulsory until the Hawke government changed the law in 1983.

Having waited all that time for equality, many First Nations people would have their access to polling booths qualified if voter ID ever became law.

Pat Dodson is a Senator for Western Australia.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout