Abandonment of Kabul is worse than the fall of Saigon

Once Afghan forces realised they no longer enjoyed air support against the Taliban, ‘psychological collapse’ occurred.

It’s understandable why both sides of US politics, along with much of American society, grew tired of a conflict that began in 2001. It’s just that there are ways of departing a war without leaving a situation of complete chaos.

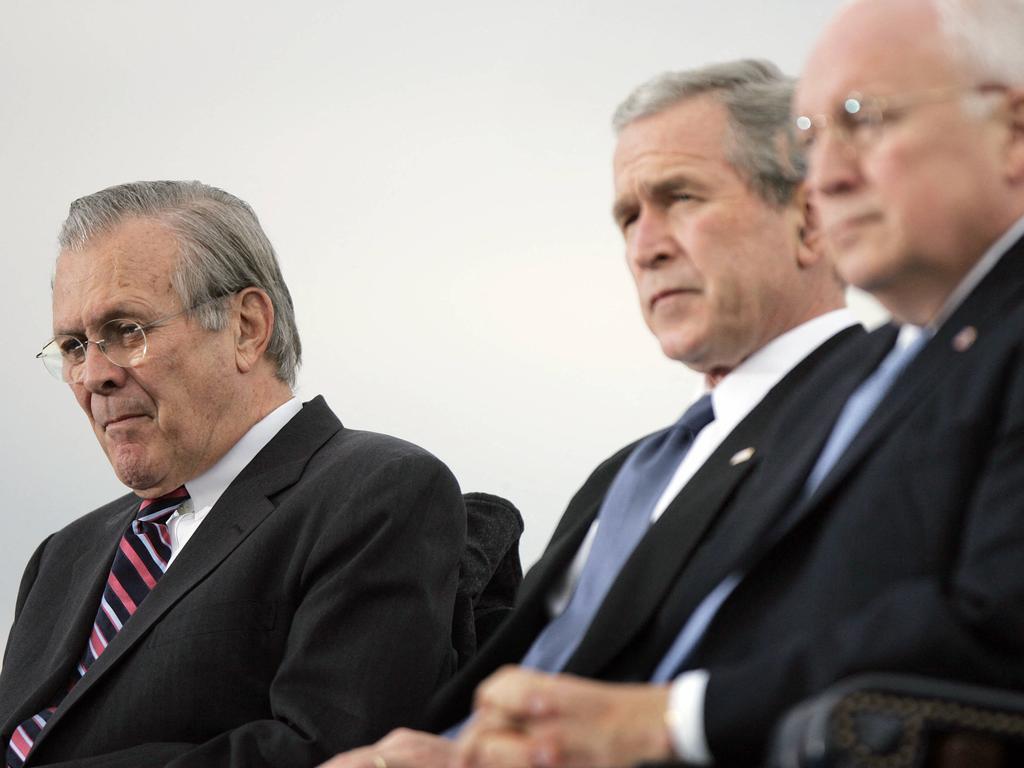

The decision of US president George W. Bush to invade Afghanistan and overthrow its Taliban government in the wake of al-Qa’ida’s terrorist attack on American soil in September 2001 was widely supported at the time by many nations. The US suffered 2500 deaths in the conflict and Australia lost 41 brave soldiers.

The war could not go on forever. But it did not have to end this way. In an address to the Sydney Institute last Wednesday, Asia-Pacific Foundation international security director Sajjan M. Gohel placed much of the blame for the current situation on American diplomat Zalmay Khalilzad.

Khalilzad was tasked by Donald Trump’s administration to secure a peace settlement between the Afghan government and the Taliban and to use pressure to achieve this end. He was also tasked to ensure that Trump’s commitment to withdraw US forces from Afghanistan was met.

In late February last year, the Trump administration negotiated an agreement with the Taliban that excluded the Afghan government and led to the release of 5000 Taliban prisoners. It set the date of May 1 this year for a complete US withdrawal. The deal negotiated gave the Taliban credibility while its forces increased attacks on the government in Kabul, despite an understanding to the contrary.

When Joe Biden came to office in January, Khalilzad’s role was continued. But the Taliban attacks on the Afghan government continued with the tacit support of Pakistan. In view of the deteriorating security situation, Biden extended the date of withdrawal from May 1 to September 11 (the anniversary of the 9/11 attack on the US). It was a grievous psychological error to place the date of effective US defeat in Afghanistan on the date of al-Qa’ida’s attack of 20 years earlier (which was planned from within Afghanistan).

Then Biden moved the withdrawal date to August 31. It was no surprise when the Afghan government fell on August 15, in view of the evident confusion of the Biden administration.

The catastrophic scenes at and around Kabul’s airport as Afghans who supported the coalition forces try to escape their likely fate at the hands of the Taliban are a direct consequence of the US decision to withdraw its remaining forces in Afghanistan – which had not experienced a casualty for more than a year.

As retired US Army general David Petraeus said on Fox News on August 14, the US withdrawal prompted the removal of remaining NATO forces and contractors, some of whom maintained the Afghan Air Force. Once Afghan forces realised they no longer enjoyed air support against the Taliban, what Petraeus described as a “psychological collapse” occurred – the consequences of which are evident today.

In January 1973, Richard Nixon announced a ceasefire between the US and North Vietnam, but his administration attempted to provide military aid to the Saigon government. Nixon’s intentions were frequently blocked by US congress. Then impeachment proceedings against Nixon over the Watergate scandal began in May 1974 and he resigned as president in August 1974.

After that, Gerald Ford (who replaced Nixon) had even greater difficulty in providing military support to South Vietnam. Eventually, in late April 1975 Saigon fell to the well-equipped North Vietnamese army, which was supplied by the Soviet Union and to a lesser extent by China. This led to the scenes of Americans and their supporters attempting to depart Saigon by means of US helicopters landing on the roof of the US embassy and taking their human cargo to US Navy ships in the Pacific Ocean.

In other words, the Nixon-Ford Republican administration did not make a conscious decision to abandon Saigon. It simply could not support South Vietnam against North Vietnam by means of weapons and finance due to opposition from within congress.

The Biden administration has not suffered any such restraints. US actions on the ground in Afghanistan were determined by the White House and not by congress.

It is impossible to imagine how a re-elected Trump administration would have responded to the events of recent months. However, it’s likely that the unpredictability of Trump, along with his detestation of defeat, could have ensured some restraint on the part of the Taliban. Clearly the Taliban does not fear Biden.

In any event, Kabul fell on Biden’s watch – much to the delight of the US’s opponents and much to the advantage of various Islamist terrorist organisations which may well seek refuge in Afghanistan as they plan future attacks on the West.

Sadly, it seems likely that the US, Australia and other nations that supported the coalition cause in Afghanistan will not be able to provide refuge to many Afghans. That’s the inevitable unintended consequence of the US’s sudden withdrawal and the earlier-than-expected Taliban victory throughout the country.

Scott Morrison has acknowledged that Australia will not be able to get out of Afghanistan all of the Afghans who deserve our support. But at least the Coalition is trying to provide an escape route, with some success.

When Saigon fell in April 1975, Gough Whitlam’s Labor government showed scant interest in providing refuge in Australia to the anti-communist South Vietnamese who wanted to flee the conquering communist regime. As Whitlam said at the time, he did not want anti-communist Vietnamese in Australia.

Vietnamese refugees began arriving in Australia in large numbers after the election of Malcolm Fraser’s Coalition government in late 1975. The fall of Kabul and Saigon have their similarities – but also their differences.

Gerard Henderson is executive director of the Sydney Institute. His Media Watch Dog blog can be found at theaustralian.com.au.

Contrary to some claims, the US’s abandonment of Afghanistan this month is not comparable with the US’s abandonment of South Vietnam in April 1975. It’s worse. However, Australia’s response to the humanitarian crisis that followed the defeats of the governments in Kabul and Saigon is far better today than it was almost a half-century ago.