Aaron Sorkin’s To Kill a Mockingbird soars beyond culture vultures

In his stage adaptation of Harper Lee’s classic, would Aaron Sorkin take a red pen to the tale to reflect modern-day pieties? How would the social forces of #MeToo appear? I need not have worried.

Harper Lee’s 1960 classic about Jim Crow-era prejudice in the American deep south is the closest thing we atheists have to the Bible. It moves us, educates us, changes us, implores us to respect individual dignity, insists justice applies to every single one of us. It challenges us to step into the shoes of others, the marginalised, the victims of prejudice, the ignorant and even the wicked.

Stylistically, and substantively, how would Sorkin leave his mark on this magnificent story? New York-born Sorkin is the writer of the dazzling, fast-talking best seasons of The West Wing, where his fictional Democrat White House has earned him a halo from American left-liberals.

Lee’s novel moves to a different beat, its timbre central to the compelling story of injustice and intolerance in Maycomb County during a couple of summers in the mid-1930s. How could Sorkin’s play, or the cast, possibly compete with the 1962 movie featuring Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch?

Would Sorkin rise above the dreadful fad, these days more at home among left-liberals, to take a red pen to old books to reflect modern-day pieties? Altering words, changing characters to avoid causing offence. Each modification stripping meaning from great works.

How would the social forces of #MeToo appear on Sorkin’s stage in a story about a man wrongly accused of rape? Would Sorkin mess with the profound principles of equality before the law and the presumption of innocence? Would Lee’s great work groan under the weight of Sorkin’s own politics – the screen writer said he read comments on the Breitbart website to understand the character of Bob Ewell, the ignorant, racist, poor farmer who wrongly accuses Tom Robinson of raping his daughter, when he is the abuser all along? Surely Ewell wasn’t Sorkin’s version of a Trump voter?

I need not have worried. “All rise” is one of the early lines in Sorkin’s play. It is an instruction, not just to the Maycomb jury as the judge enters the courtroom where Robinson’s fate would be sealed.

“All rise,” announces Scout throughout the play and when the curtain comes down, as if directing us to rise above our modern instincts and politics to return to first principles.

Though I was a few years late getting to Sorkin’s stage version of To Kill a Mockingbird – it opened in December 2018 – waiting has made the watching more riveting. His play is more important in 2023 because, on many fronts, things have only gone from bad to worse.

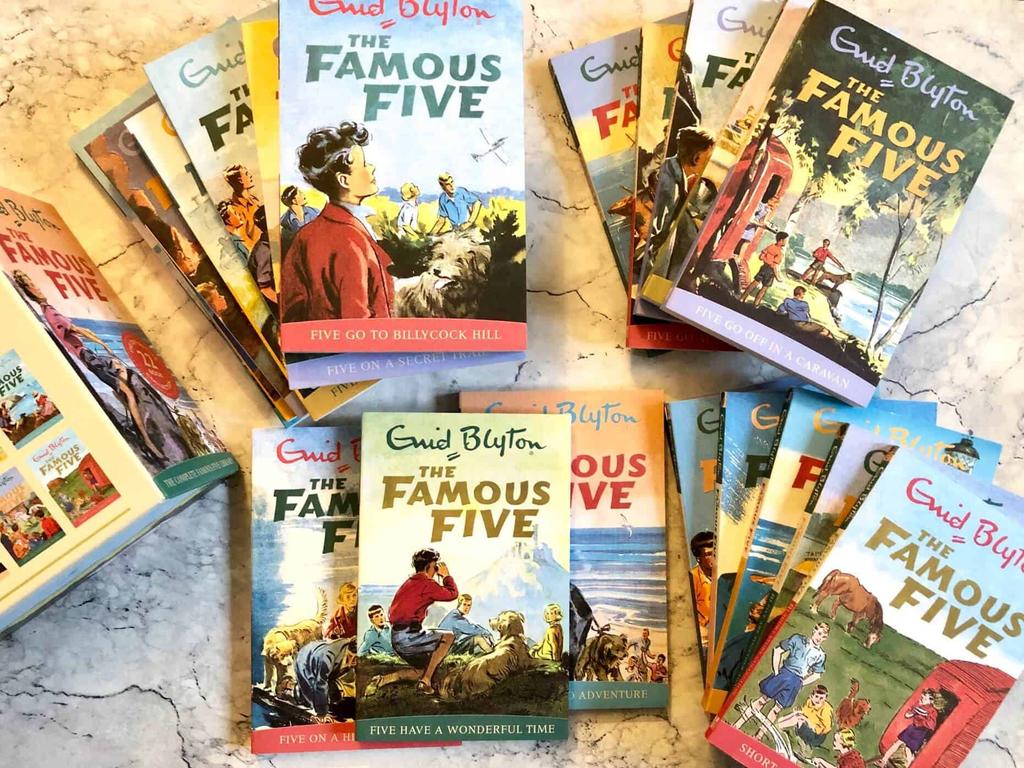

Sorkin rises above the increasing political and puritanical din of our own society. He pays little heed to those frequent demands for classic books to be sanitised to reflect modern-day sensibilities. Those puritans who most recently came for Enid Blyton, again, have been working at this sanitisation project for years.

Publishers had already mangled Blyton’s Faraway Tree series, turning Dame Slap into Dame Snap. Dick became Rick, with he and Julian sharing the household chores with female characters. Stupid stuff that shows no respect for kids. I’ll bet no little girl grows up thinking she has to do the household chores after reading Blyton’s books. Giving a kid an old book allows them to understand another era. We should trust them more.

More recently, publishers came for Blyton’s the Famous Five. Instead of “Shut up, George”, George is told to be “sensible”.

Over a decade ago, an English professor at Auburn University in Alabama joined with a local publisher to produce a new edition of Mark Twain’s classics, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer. They replaced the N-word (which appears more than 200 times) with slave. The professor worried that the word offended too many students.

Like Huck Finn, To Kill a Mockingbird exposes the evils of racism. Yet, over many years, some American schools and libraries have removed Lee’s book from school reading lists – to protect kids from offensive language, such as the N-word.

Alas, history is confronting. Cruel, racist language helps us understand that. Great literature unsettles us. It forces us to think about our reactions. If we’re offended, we think about why we’re offended.

By resisting these sanitising urges, Sorkin has produced a refreshing, confronting masterpiece for the 21st century. To be sure, no one wants to hear the N-word. That night in London I heard it more times than I care to count, every time landing with a thud, as if accompanied by a fist. That was surely Sorkin’s intention: we need to wince at the vulgarity and viciousness of the word, so that we might feel, even a tiny fraction, the outrage, hurt and affront it causes black people.

Sorkin, in short, trusts his audience. And just as we need all the help we can get to stop the defacement of classic books, it’s the same when it comes to protecting fundamental principles.

In Mockingbird, that principle is that each of us, regardless of our skin colour, our gender, our celebrity, our position, is entitled to a fair trial, entitled to the presumption of innocence, entitled to due process, entitled to confront and challenge an accuser in open court.

This needed saying in 1960 by Lee. It needs saying in 2023 by Sorkin too. The playwright rises above the roiling #MeToo movement that so frequently tries to up-end our justice system with modern-day witch-hunts and vigilante persecutions of today’s unpopular defendants.

Sorkin’s Mockingbird couldn’t be a better timed reminder that, imperfect though it is, no one has yet devised a better safeguard against jailing innocent people than the presumption of innocence. Those who pay scant regard to this principle should buy a ticket to Sorkin’s play. Once it is gone, the consequences will be truly wretched; the families and friends of #MeToo activists won’t be spared.

Sorkin’s genius is to stay true to first principles even when weaving in themes from our own era. He brings us face-to-face with the worst form of racism, a far cry from the daily misuse of the word racism where wickedly misguided accusations get thrown around for myriad ulterior motives. The exploitation of this word – racism – serves only to dilute the word. Sorkin returns power to the word, even while injecting some 21st-century race politics into this story.

Sorkin’s adaptation of Calpurnia is sassier, more argumentative, less patient than Lee’s portrait of the Finch family’s African-American housekeeper. Sorkin’s Atticus is less perfect, more unworldly.

My favourite scene captures the magic of Lee’s Atticus and Sorkin’s Calpurnia.

Calpurnia: Jem was stickin’ up for you and maybe a little bit me and you made him say he was sorry.

Atticus: I believe in being respectful.

Calpurnia: No matter who you’re disrespecting by doin’ it.

Lawyers for Lee’s estate objected to many of Sorkin’s changes, including this one. Sorkin has said Lee’s side argued a typical black maid would never speak to their employer like this in the south in the 1930s. Sorkin, who conceded other changes, stuck to his guns here. His response was: “There’s no such thing as a typical black maid. Plays aren’t written about typical people doing typical things.”

Though litigation was threatened, the parties settled before Mockingbird opened. And Sorkin’s reinterpretation of other characters remains intact: Tom Robinson is a more articulate defender of his rights; Bob Ewell is a fouler version of Lee’s ignorant, poverty-stricken father of the girl who accuses Robinson; Dill is a more tragically marginalised kid with a dysfunctional mother.

Sorkin’s Mockingbird shows how a much-loved classic should be respected and can be deftly modernised without being sanitised in any way. The lasting power of this play, beyond the laughs, the tears and the cheers as the curtain fell, comes from Sorkin remaining true to first principles.

Please don’t mess with it, I said to myself, as I sat down in the packed Gielgud Theatre in London a few weeks ago to watch Aaron Sorkin’s To Kill a Mockingbird.