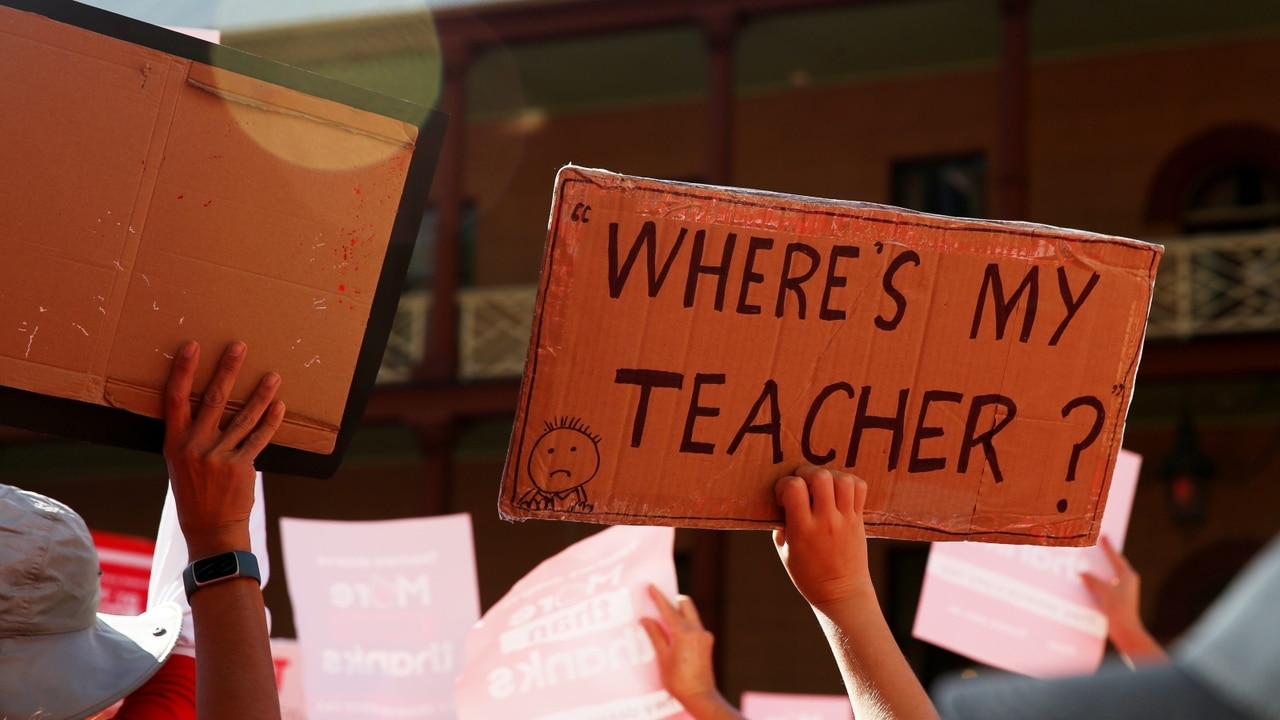

A teaching vocation is exactly what is needed if the profession is to revitalise its reputation

Teaching doesn’t have the lustre of other roles but is one of the most important jobs.

Who among the year 12s who are soon to complete their final exams is seriously considering teaching as a career?

A few observant students in this national cohort may have noticed how hard their teachers worked to get them over the line, doing practice exams and essays, holding early morning revision classes, responding to frantic emails, encouraging and assessing their progress, gently reminding them that they are more than the number that the blunt instrument of the Australian Tertiary Admission Rank will assign to their efforts after 13 years of schooling.

They will know that many of their best qualities, their character, capacity and conviction, will not be counted under this particular assessment regime. They will know there is a rich and rewarding life beyond school and that whatever a score or piece of paper or an academic award denotes, it does not define them now or in the future.

They will know this because many teachers will tell them there are many pathways to accomplishment and success. There will be prizes for some and relief for others, and the necessary rearranging of preferences for post-school study or work.

Some students, however, do know exactly what their teachers have done for them, conscientiously and uncomplainingly, not only in year 12 but throughout their educational journey, so they may access courses that are far more glittering, socially propelling and remunerative than this profession, which looks more and more like a service provider glibly marketed on train station hoardings in leafy suburbs.

These teachers have been at the job for years: devoted, expert, wise, always alert to the teachable moment, accessing good resources, able to read the class or the student. They know how to pitch or re-create a lesson because something unexpected has occurred.

The curriculum content may require a quick rejigging or to be put on hold while exigencies are dealt with. The pandemic taught teachers to pivot even more expertly. For thousands of students across the nation they were the faces of cheerful consistency, a reliable presence in uncertain times.

Today, teaching as a career is suffering from severe reputational damage. Everyone knows the old 9-3 joke about the job is way off the mark. With increased regulation, compliance, the changing nature of the classroom, shifts in educational pedagogy and a move to a wellbeing paradigm, teaching is not for the faint-hearted.

Societal expectations now mark the school as a one-stop shop for the remediation of all sorts of social deficits, time-poor parenting or the latest issue du jour. Everything from consent, harm minimisation, social media vigilance and cyber bullying, goal setting, safe partying, study skills, critical thinking and the myriad soft skills that enable human beings to get along with each other are now the remit of the school.

Literacy and numeracy are fighting their corner for a slice of the timetable pie as our results decline. We worry about opportunity and access for children of varying intelligence, prior learning, motivation, social background, work habits and behavioural impact, who are often all in the same classroom.

I am counting down the days until the end of term when I will gently close the doors on 30 years in the teaching profession. From this vantage point I can reflect on what I have observed of pedagogical and social changes across those years, wonder about how the profession will proceed in changing times, and trust that there will be the next generation of teachers who will devote themselves to this most worthy of callings.

I am grateful for the lessons I have learned along the way and the colleagues who have inspired me. I have a sense of accomplishment in being, as St John Henry Newman wrote, a link in the chain, a bond of connection between persons.

That is what teaching is about; that bond between an adult and a child where knowledge and skills are passed on to be re-created for an emerging society, that Tomorrowland that we ourselves will not inhabit. Or as GK Chesterton wrote, education is simply the soul of a society as it passes from one generation to another.

I am grateful for the good times I had in the classroom, the light bulb moments, the laughter, the occasional and necessary tedium, the student successes and challenges, and the autonomy I had to create my own learning community. I watched with pride as a student received a Premier’s Award or wrote a lovely poem or was able to deliver a powerful speech. I was proud of those students who listened to feedback, asked questions and made headway because they sought help to improve. I witnessed the kindness of students helping each other as they began growing into their future selves as they learned to collaborate and share ideas and dreams.

I may have flung in the odd big word to keep them on their toes and insisted on good manners, but mostly there was a happy reciprocity where I was able to teach and they were able to learn. A climate of encouragement is key to any sort of forward momentum. Gently prodding students to reach beyond their grasp can also provide a sense of achievement.

The word vocation is rather old-fashioned, antediluvian even, with its hints of service and devotion and implied longevity, but that is exactly what is needed if the profession is to revitalise its reputation.

We need to ensure that we have those teachers who can survive beyond the five-year mark; those teachers who are committed for the long term. They need a personal vision synergistically aligned with the institutional one. They understand at a granular level that this profession is the most important future builder for this nation.

We need stayers who have good reasons to stay. Not careerists who put in a fleeting two-year stint, then move on without a backwards glance. A revolving door is no good for any institution, as corporate knowledge is lost, institutional cohesion evaporates and staff become siloed through a constellation of factors to do with age, experience or different ideological or philosophical imperatives.

This is because stayers have experience, wisdom, knowledge, resilience and goodwill – the latter being the lubricant that gets things done and creates collegiality and camaraderie, that essential pulling-together in the same direction for the good of the students. I was the recipient long ago of just such teachers. Some of those lessons about content stuck, but what remains is their attitude, conviction, steadfastness. They knew and cared about me. They encouraged me, gently steering me away from the pretentious verbiage of trying too hard to impress to something a little more simple and eloquent.

We need the best if we are to fulfil the dream of being a knowledge nation. We need teachers who are masters, if not of the universe then at least of their discipline. We need teachers who have demonstrated they have academic ability. We need teachers with a clear moral purpose. We need teachers who believe the job they do is crucial for the future of our national wellbeing.

We need teachers who understand that our young people need encouragement and affirmation, the occasional timely admonition if required and the growing sense that they shape their individual destinies with the choices they make and the opportunities seized. Those individual destinies will coalesce into this country’s collective future, so we must ensure we get the building blocks right.

Most teachers are professional, innovative, passionate and as empathetic as they are allowed to be in an industry that is becoming increasingly strangulated by edu-babble, online compliance, a deluge of data, this week’s shiny pedagogical fad and the ongoing tyranny of online reporting.

Yes, my students are ahead of me in all things tech with their subterranean adolescent networks and antennae wired for what is trending on TikTok. This is their world, but it does not mean those tried and true methods of the past have lost their efficacy. We now have to engage short attention spans and use adaptive and assistive technology but we also know that practice, patience and persistence are still keys to knowledge, skills and understanding.

The 2024 What Kids are Reading report indicates that students are reading easy and familiar books and that their comprehension skills are declining. They do not have a sustained focus and their vocabularies are impoverished. We need to challenge them to read the book properly and not think the film version will pass muster for a proper literary analysis.

I am over the latest trend of digital “busy work” to keep the students engaged. This is lucrative for those who create these platforms, but, it seems to me, this gamification is really just a time waster that doesn’t translate to better literacy skills. Kahoots may be fun in the immediacy of post-lesson revision, but does this help information retention? Perhaps there should be some data analysis on that.

Across the course of my 30-year career I have navigated much change, most of which I have managed and some of which leaves me floundering in its wake. Artificial intelligence is out of the bottle and I fear for the authenticity and depth of student work when ChatGPT can create a perfectly plausible B+ essay, minus the occasional hallucination. I worry that students are outsourcing the hard yards of doing foundational work for themselves.

It saddened me last week when some of my year 7s told me they did not actually have signatures, so used are they to typing everything. They have not developed their own maker’s mark, the penmanship to write and own their uniqueness in the world. All I can see is a dystopian scene out of Gattaca where prospective space cadets type robotically into computers, their individuality noted only when they make a mistake. The loss of the art of handwriting is a serious misstep, especially when authentication is needed.

I wonder how our thousands of students have managed to usefully convey what they know to the subject assessors. Legibility seems to be thing of the past. Those samples of a beautiful hand are now something of a curiosity in this age of type and swipe.

Our bureaucrats want better results as they talk up literacy and numeracy, but decorative digital diversion will not be parlayed into better results, no matter how much money is spent. Digital platforms often decontextualise content so that learning results are falsely inflated. Back in the classroom, the possessive apostrophe has gone AWOL and it’s and its are beyond redemption.

What we need urgently are graduate and mature-age teachers who can pass the Literacy and Numeracy Test for Initial Teacher Education Students, or LANTITE, pitched at year 9 literacy and numeracy, to guarantee they know the basics. We cannot afford to let standards drop any further. Too often we hear university lecturers bemoan the quality of undergraduate essays. This is after 12 or 13 years of education. It is to be noted that the recruitment of the top 10 per cent of graduates into the teaching profession in Singapore keeps that nation at the forefront of international educational success.

The over-reliance on laptops is an issue where children can effectively outsource thinking and misplace the zing of creating something entirely original. Multi-tasking is detrimental to the comprehension of content. Thankfully, the fad for student-directed inquiry has been exposed as a sham.

Students need direction and instruction before they take those leaps of imagination or innovation. They need frameworks and scaffolds and templates and models. They need the basics in place at the end of primary school so they can start secondary school with confidence and not languish as one of the current 10 per cent of those whose reading skills are well below the standard for their age, according to La Trobe University education professor Pamela Snow.

Two decades ago I used to go to student evenings to spruik the joys – and challenges – of teaching as a career. I spoke of hard work and fun, of collegiality, of students who made you think again, the just-in-time learning of being thrown into a new subject area, the corrections, the responsibility and the freedom of one’s own classroom, management issues, parents, the whole eventful kit and caboodle that makes up school life.

These days teaching, unlike law and medicine and engineering, has few people to actively promote it as a serious career option, a first choice (not third or fourth or last or desperate) for those who have the capability and understand how profoundly important this job is. This is not just about literacy and numeracy. It is about hearts and minds and moulding the future.

Teaching does not have the lustre of other professions, yet it is one of the most important jobs of all. Everyone has a good – or bad – teacher story because the school experience and where it leads shapes that individual’s future. This individual future multiplied by all the futures being readied – or not – in the classrooms of the country predicates the sort of country we become.

Teaching is not for the faint-hearted, nor should it be for those who have not proven to have the intellectual capacity and tenacity that is required of school and university study. A whatever attitude and an ATAR below 50 does not inspire confidence that the profession is attracting those who could really be transformative in the classroom. Enthusiasm cannot replace intellectual ability.

We need to attract those who have the intellectual capacity, emotional connection, the preparedness to work hard and sometimes go above and beyond designated hours. We need people who will be able to navigate uncertain terrain, a world of disruption and fragmentation, and bring into the class their calm, civil and conciliatory ways as a model for public discourse.

Teaching is multifaceted and emotionally demanding. It is public and performative. It involves face-to-face interactions with students – and staff – of all dispositions and capacities. It involves lesson planning and hours of correcting and meetings and professional development and emails and yard duties and stretching budgets and noticing that a student wants a word quietly.

The teaching profession has given me my own small stage, my very own captive audience, where I could tell stories and bring up topical discussions about things that mattered, sometimes the existential questions, occasionally a bit of pop-culture frippery.

I have been a sounding board, a mediator, a critical friend, a mentor. I have been challenged, too, and have had to hold my ground. Sometimes I may have talked too much and strayed off topic, allowing some circumnavigational chat or incidental gem to drop into the lesson. Sometimes it is what is not scripted that becomes the meaningful life lesson.

There has been a happy congruity between who I am and what I do. Words have been my bread and butter as I have tried to pass on some of the joys of the English language to my budding poets and philosophers, screenwriters and comedians.

I started teaching in my late 30s, having had travel adventures and other employment and their consequent stories and insights to add to my classroom toolkit.

As I leave the profession for adventures of a more sedate kind, I remain grateful that I have had the opportunity to lift the gaze of the young. They can look ahead with some optimism and with a repertoire of skills that will enable them to contribute to the next chapter in our Australian story.

I trust that education will remain the engine room for this country’s future prosperity and the flourishing of all its citizens.