A once hated Peter Tatchell is now seen as a human rights visionary

Beaten to the point of brain damage and reviled the world over, the Melbourne activist has finally been vindicated as a visionary.

The countries that need Peter Tatchell most are those that want him least: Russia, Zimbabwe, Qatar, Iran, the Palestinian Territories, China – to name a few.

And when he started his activist life in Melbourne in 1966, campaigning against capital punishment and the hanging of Ronald Ryan, and for Indigenous rights, and against the Vietnam War, we didn’t want him either.

That’s not why he left Melbourne for London in 1971. There was a more practical reason – he did not want to fight in Vietnam.

He was opposed to communism, but not as much as he was opposed to the US and Australia throwing conscripted youth on to an unwinnable bonfire.

He has taken a beating for his activism, both physically and figuratively. Few would have lasted the distance – five decades and counting. The first time Tatchell, now 70, was assaulted, it was almost a multicultural affair.

In 1971, he was part of a group that occupied the London offices of Aeroflot to protest the detention and enforced psychiatric treatment of dissidents in the Soviet Union. Russian staff came out with the most American of weapons – baseball bats – and clubbed the young “rebels”.

Almost a lifetime later, he is still taking the challenge of human rights for all up to – and often inside – countries hostile to the notion. And they don’t like it.

Last month, he bravely took on Qatar that this month hosts the World Cup, an event the Gulf state effectively cheated its way to “winning” over Australia and the US.

Activists in Muslim lands can be murdered by the state.

Four years ago, the Saudi government, annoyed by dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi, lured him into its Istanbul consulate where Saudi agents taunted him, drugged him, killed him and sawed his body into disposable pieces, none of which was found.

Arriving in the Qatar capital Doha, in a soon-to-be-revealed T-shirt reading “#QatarAntiGay”, and then holding up a placard reading “Qatar arrests, jails & subjects LGBT to ‘conversion’ ”, the lanky Tatchell, as white as a cigarette paper and not much wider, stuck out, which was the idea. He was quickly surrounded by state security officers and police, detained for some time and, according to Tatchell, told that it would not be in his best interests to remain.

He came home to Australia for a short visit. Doha was a rematch of sorts. He’d made a similar one-man protest in Russia as it hosted the World Cup in 2018 standing beside the statue of Soviet war hero and defence minister Marshal Zhukov near Red Square with a placard that read: Putin fails to act against Chechnya torture of gay people.

With Russia on better behaviour with the world about to watch on, Tatchell was taken to a police station and given a court date.

Back in Chechnya, things were grim. Vladimir Putin’s puppet president Ramzan Kadyrov had launched a murderous purge of gay men and women during which they were rounded up and tortured. Families were encouraged to kill gay relatives, some of whom were reportedly released from detention so that their families could do just that. Kadyrov now insists there are no gays left in his country.

They need a Tatchell. So how far would Tatchell go to, say, advance the cause of human rights in Muslim lands. Would he march on Mecca during the hajj? It would make headlines.

“Well there are certain things commonsense dictates I shouldn’t try,” he says with a chortle. “I’ve been doing human rights campaigning for 55 years. I intend to carry on for another 25 – I wouldn’t be able to do that dead or locked away for decades.”

Mecca may be off the agenda, but he has made his mark in other hostile territories, and suffered the consequences, not least in his adopted hometown.

There was little sympathy for him in England or Europe as he challenged governments to deliver equal rights for everyone, with a particular focus on gays.

He would be regularly beaten – he thinks he has been attacked about 300 times, but was soon back on the streets of London and Berlin by unpopular demand.

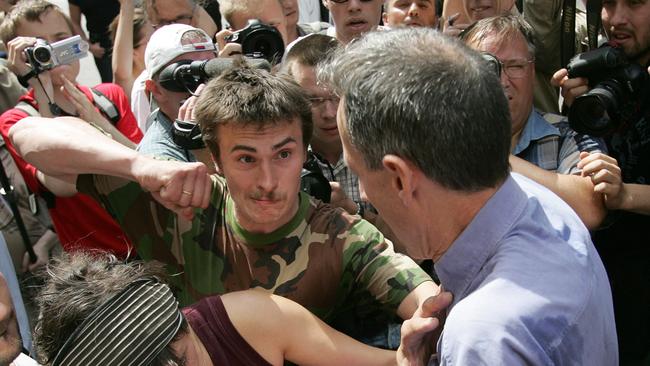

A particularly nasty incident is recorded as part of the recent documentary on his life, Hating Peter Tatchell. He’d gone to Moscow to join a protest against mayor Yuri Luzhkov’s ban on Gay Pride marches, which Luzhkov described as satanic.

“I was very badly beaten by neo-Nazis (chanting “death to homosexuals”) with the connivance of the police and riot squad. They allowed the far-right extremists to beat me almost unconscious. Then I was arrested and my attackers were allowed to walk free.”

But by then, the man once commonly described as the most hated in Britain, had had a change of status. Besides slaughtering his enemies, Robert Mugabe had done few things for others, but one day in Belgium in 2001, after a foiled but newsworthy attempt in London, Tatchell attempted a citizen’s arrest on the Zimbabwean president to charge him with crimes against humanity. Tatchell assumed it wouldn’t go well, but even he was surprised by the ferocity of Mugabe’s goons as they moved to protect their boss by bashing Tatchell senseless. One even drew a gun.

“People concluded that if President Mugabe is prepared to have his goons beat unconscious a peaceful protester in broad daylight in a European capital city (and home of the EU), in front of the world’s media, just imagine what he’s doing to his own people while no one is watching,” Tatchell said.

He suffered some brain damage and a long-term injury to his eye. “But I was determined to do something to help shine a light on the terror campaign that Mugabe was unleashing against all critics.”

Overnight, Tatchell became a hero, which remains his status. And it adds weight to his ceaseless campaigning on which he works about 15 hours a day.

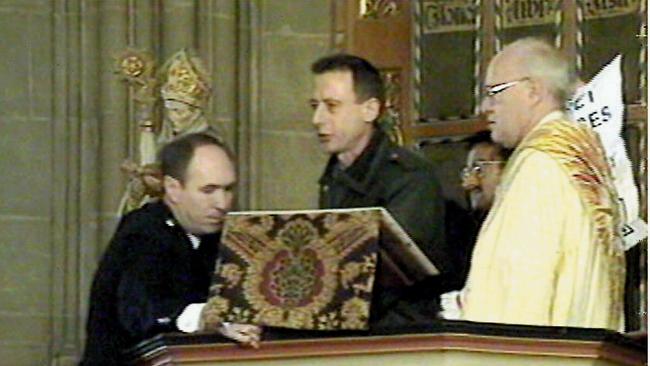

In Hating Peter Tatchell, he is praised by the likes of Elton John (“The whole gay community owes you for your bravery and your courage”) and Stephen Fry, for his bold campaigns on behalf of human rights that were then not universally accepted, but the most telling moment comes when an ageing former archbishop of Canterbury George Carey reminisces about the day in 1998 when Tatchell and friends, frustrated that they could not meet the archbishop to discuss the Church of England’s hostility to the gay community, walked into the pulpit on Easter Sunday. Tatchell delivered an “alternative” sermon condemning Carey and his church (unwittingly, the grumpy parishioners added to the theatre slow hand clapping and chanting “Out, out”) on a day when it was being televised internationally.

The protesters were violently ejected. At the time, Carey was furious and condemned Tatchell. “It was a kind of scorched earth policy; you don’t make friends that way.” No surprise there – Tatchell was almost universally condemned.

Today Carey, like so many others, has a different view. He says simply: “He has been a figure for good and equality. He’s rocked the boat and there is a sense in which there is a parallel with Jesus Christ.

“Jesus was prepared to stand up to the powerful people in society (to) represent smaller people. No one can doubt that he is on the right side of history.” An Australian right-wing commentator last week put it more succinctly: “He’s got balls as big as church bells, that bloke.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout