A game changer for the American alliance

After the ignominious rout in Afghanistan, four former PMs agree … Australia must now become more self-reliant.

There are now dramatically competing visions of America. Take your choice between Biden’s early 2021 pledge to the world that “America is back” aiming to “repair alliances and engage with the world”, and his personal capitulation to the Taliban while pouring inexcusable abuse and blame on the Afghans who were America’s partners for 20 years. This is self-serving moral infamy.

Inquirer has conducted interviews with four former Australian prime ministers in office during the Afghanistan campaign – Tony Abbott, Kevin Rudd, Malcolm Turnbull and John Howard – that reveal varying and frank alarm about Biden’s withdrawal and their different views about the future of the US alliance.

While Donald Trump was a known untrustworthy president, Biden’s Afghanistan call is so devoid of judgment and courage that it raises a fog of doubt about Biden himself and about America’s democratic sustenance as a reliable great power.

Tony Abbott, a realist on Afghanistan, told Inquirer: “I fear that the fall of Kabul and the return of the Taliban is not just a catastrophe but a strategic watershed as well. How much fight is left in Biden’s America? More than currently seems I suspect, but that’s the question that all US allies must now ponder and adjust to accordingly,” he said.

Abbott warns of more terrorist attacks, and of China and Russia being “more adventurist now that this President has declared that a country that had cost so much is no longer worth a single American life”.

Abbott said: “This is not a perception that can be allowed to stand if alliances are to last. Australia must step up to help avoid an American retreat with calamitous consequences.”

His message is Australia must do more and inject “more spine” into the US alliance. For Abbott, this capitulation affirms his warnings of recent years. These were memorably expressed in his 2018 Washington speech insisting Trump must be taken seriously because, as Abbott said, “the legions are going home, American values can be relied upon, but American help less so”. Abbott said this week his fear was that a “Covid-obsessed West might sleepwalk past the new reality.”

Biden’s justification for his Afghanistan surrender – that his partner lacked “the will to fight” – suggests Biden, like Trump, will demand far more from US allies. Reciprocity is assuming a new meaning. Australia must become more self-reliant – for itself, and for the alliance.

Kevin Rudd has been issuing his own warnings over the past few years, different from Abbott but also ominous. Rudd told Inquirer: “The Australian public and body politic needs to understand we are in the midst of a profound paradigm shift in global and regional geopolitics. It’s about the rise and rise of China and an America that continues to question itself about its future strategic role in the region and the world.

“It is an open question where America will be in 10 years time, given the divisions in the US body politic, the domestic distractions on both sides of American politics and a ‘world weariness’ evident in many parts of the Congress.

“What that means for Australia is we should plan for the best, which is a robust regionally and globally engaged America, while simultaneously planning also for the worst – an America that begins to retreat. That means a radical reappraisal of our national economic and strategic preparedness to manage our own core strategic interests.”

Rudd said he was not advocating any weakening of the US alliance as our essential strategic guarantee – just the reverse – but Australia “would be willingly blind not to recognise the palpable evidence of an isolationist dimension in America’s world view that is becoming stronger rather than weaker”.

Rudd’s warning could not be sharper. On August 14, before the fall of Kabul, he issued a statement saying if it fell it would invite parallels with the fall of Saigon, it would constitute a “major blow” to US standing, and he called upon the Biden Administration to “reverse the course of its final military withdrawal”.

This was an extraordinary statement by a former Labor PM. Rudd quoted from his book earlier this year, The Case for Courage, in which he said that the challenges facing Australia demanded higher military spending, an even deeper military partnership with the US, a commitment to a “Big Australia” and stronger Indo-Pacific and Pacific Island ties.

Malcolm Turnbull told Inquirer: “I respect the decision President Biden took in the circumstances. Biden’s defence of his position is the same as Trump’s. Yet the outcome is appalling and many people are left abandoned. This has damaged America’s standing and prestige.

“The people I know who know Afghanistan best all believe America should have retained a garrison force in Afghanistan. That’s the real question: could keeping a garrison in place have maintained the ring and supported the Afghan national forces and ensured the Taliban takeover did not occur.

“The problem in politics is that you are often faced with bad options. It was not palatable to have kept forces there, but what we have seen now is even less palatable.” Turnbull pointed out the US had kept forces in Europe, NATO nations, Japan and South Korea for decades. But he made the point such forces were to deter cross border aggression not fight a domestic insurgency 24/7.

On Trump’s “peace” deal with the Taliban, Turnbull said: “The talks should never have occurred in the absence of the Afghan government and their effect was to de-legitimise that government. But in Afghanistan, the fundamental problem was nation-building that involves you in civil wars and insurgencies; it’s hard, you’re seen as an invader.”

Turnbull said the issue Afghanistan raised was not just US reliability, it was American competence. Indeed, this was possibly a bigger issue.

He said the noble goals the US sought might never have been achievable in Afghanistan, but this couldn’t absolve US leaders from the dilemma they faced. What was the best outcome? Turnbull referenced the former commander of the international forces in Afghanistan, General David Petraeus.

“We set them up for failure,” Petraeus said this week. He argued the US should have left a core force of a few thousand behind but instead it had created “an infectious psychological collapse”. Petraeus said the US had not suffered a single casualty in Afghanistan in the previous 18 months. “China and Russia are having a field day,” he added, saying they were now asking other nations of America “so this is your partner?”

But on the wider question of US reliability, Turnbull was optimistic. “I don’t doubt America’s commitment to our region,” he said. “America has a far sharper, keener interest in this part of the Pacific than it does in Afghanistan.

“What this demonstrates is that with all its power and resources, US intervention in civil wars and insurgencies where you are seen as the foreign invader is fraught and it’s hard to make that work. On the other hand, defending an ally, as evidenced from Germany to South Korea, when your task is to stop the person on the other side of the border from invading, then that is a very different situation.”

This distinction is critical.

John Howard was measured but firm in his criticism of Biden. He told Inquirer: “I can understand the argument that Americans were getting weary of the prolonged involvement in Afghanistan. This decision had to be America’s call. But I am critical of the deal Donald Trump negotiated with the Taliban and in the process sidelining the Afghan government.

“I am also critical of the withdrawal that has been handled in a very clumsy manner indeed. I think you can terminate a military involvement without having to withdraw the very last soldier. Yet there seemed to be a determination to withdraw to meet a deadline – in this case the 9/11 anniversary.”

The former PM felt retaining a small military force would have strengthened the resolve of Afghan forces and, given that America still has about 30,000 troops in South Korea 70 years after the end of hostilities, that merely reinforced the question about why every last soldier had to be withdrawn now.

Asked if his confidence in the US as Australia’s senior strategic partner was eroding, Howard said: “It hasn’t yet. My initial reaction is that this bungle has taken place in the context of Afghanistan and the different views of Democrats and Republicans over how to fight Islamist terrorism.

“I still have a lot of confidence in the American relationship. I believe if it was put to the test the Americans would honour the ANZUS treaty. I think in our part of the world, Australia for many years has been the most reliable ally of the United States.”

Howard, however, has a special place as the prime decision-maker in Australia’s military commitments to Afghanistan and Iraq. In Afghanistan, Australia made two commitments – in 2001 and 2005, and it is the 2005 commitment that is the most contentious.

The Howard government’s 2001 decision to commit forces to support the US intervention in Afghanistan after al-Qa’ida’s attack on the Twin Towers was a “no-brainer”. This was one of the most justified military interventions in the past century.

It was legally sanctioned by the UN. It followed the invoking of the ANZUS treaty for the first time. With the Taliban protecting al-Qa’ida leader Osama bin Laden, it was strategically and morally justified in order to track the terrorist organisation responsible for so many civilian deaths and depose its protecting state. Australia’s role had bipartisan Liberal-Labor support.

Howard said at the time that if the common bond of “liberty, fraternity and justice” along with the ANZUS treaty meant anything then Australia would stand with the US. Given the current debacle in Afghanistan, it is vital to avoid thinking that Australia’s original intervention was a mistake. Nothing could be more wrong.

It was the drawdown of forces from Afghanistan in 2002 and 2003 and the fatal Bush government decision to invade Iraq, with Australia’s participation, that helped produce the Taliban’s resurgence. In 2005, Australia’s defence establishment had no appetite to return to Afghanistan. But Howard and his foreign minister, Alexander Downer, carried the day. Defence force chief Peter Cosgrove was distinctly reluctant, fearing the slippery slope. “He played a dead bat,” one insider said.

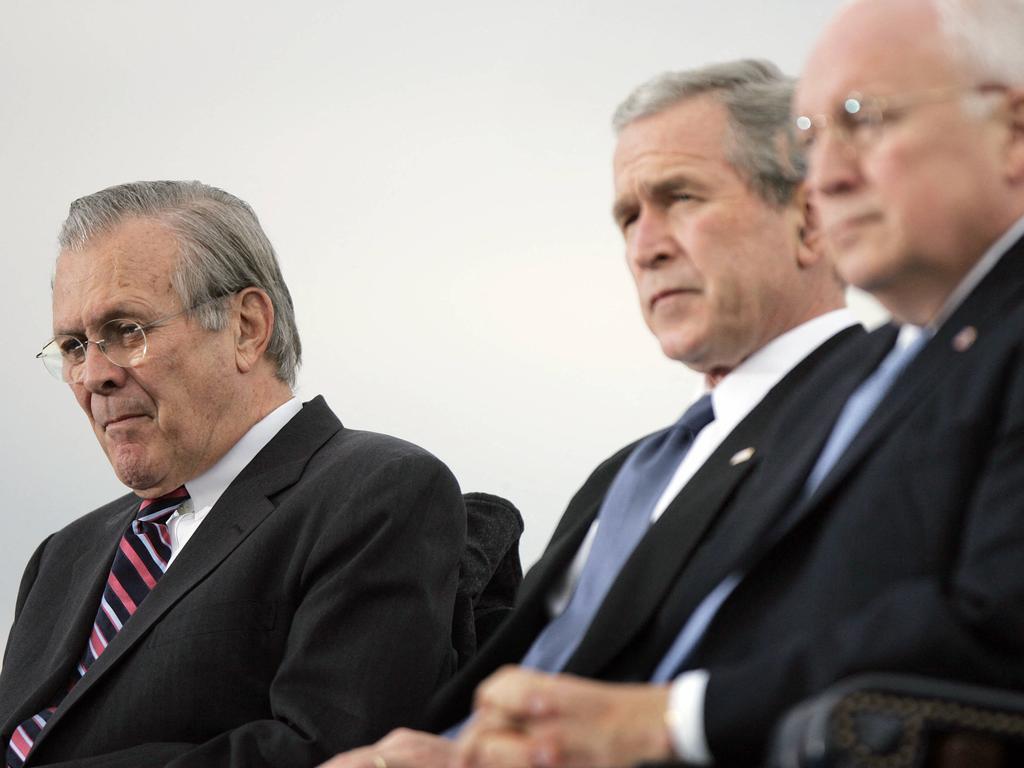

But Australia went for a different and less-defined nation-building mission, a mission that eventually failed with a total cost of 41 ADF lives. President George W Bush bears much of the blame for an ill-conceived project. But Labor was enthusiastic – ALP leaders tended to see Afghanistan as the “good” war and Iraq as the “bad” war.

Two foreign policy analysts, Sydney University’s James Curran and international security expert Alan Dupont, both warned of the need for an Australian rethink. Curran said: “If the circumstances in Kabul and decision-making in Washington doesn’t prompt a major reassessment of our strategy for alliance management, then we are on a waltz to nowhere.

“We have been putting off this reckoning with a different America for too long. In Afghanistan, America is once more facing up to the limits of its power. Yet the political class and sections of the Canberra national security establishment have been in denial about this since Trump came to office. They tried to dream the old Cold War America back. But that America is gone.” Curran added that the public needed to be briefed about its future – the need for more Australian self-reliance “than we have known before”.

Dupont said: “Australia has to rethink its alliance relationship with the US, and the sooner the better. Paying our alliances dues with token contributions won’t work anymore. If we want a security guarantee and the protection of the US nuclear umbrella, we will have to pay a higher premium. That means greater burden-sharing and greater US access to our defence facilities, particularly in Northern Australia.

“Going it alone makes no strategic sense and America remains an indispensable ally, the only country capable of countering China’s formidable military,” he said. “But with China the focus this puts Australia into a stronger position within the alliance and increases our leverage with the US. Morrison’s challenge is to leverage Australia’s heightened value as a dependable, strategically located ally to secure improved access to US defence technology.”

It is far too early to draw firm conclusions about the Biden-Afghanistan-“America is back” conundrum. But here are three benchmark points.

First, the Howard model of US alliance management that worked effectively for a generation – minimal commitments for maximum strategic gain – is over. There is a new ballgame. Allies must do more in order to exert greater influence on US decision-making but also to insure against the US retreat – Rudd’s worst fear – and that means a transformed sense of self-reliance within the alliance.

Second, forget any notion of Australia distancing itself from the US on the grounds of senior partner unreliability. The US unreliability risk is growing but the strategic danger from China is growing at a faster rate. This means Australia is sucked into an inescapable dilemma – it needs America in the great Indo-Pacific struggle now unfolding but knows much of the American public has no stomach for great power sacrifices or commitments.

Third, Australia is now locked into the big league. The US/China rivalry is totally different from Australia being a tag-along loyal coalitionist in Afghanistan and Iraq with no say on big strategy. The calls the US and China will be making on trade, technology, finance and military issues have the potential to do immense good or immense harm to Australia. Our voice and role is far more important in the Indo-Pacific than it ever was in the Middle East. And it needs to be exercised.

The ignominious rout in Afghanistan triggered by President Joe Biden is the latest evidence of the strategic wake-up call Australia needs to make – rethinking the US alliance in terms of our rhetoric, our responsibilities and our self-reliance.