A cloned sheep in Scotland startled the world – and changed it forever

It is 25 years since Dolly the sheep was born. Cloned from the cells of another, long-dead animal her arrival shocked us all. So what did Dolly teach us?

They were matters of life and death – the first days of July 1996 were a time in which we cross-examined ourselves about the big issues.

On Monday, July 1, that year the Northern Territory Legislative Assembly passed a controversial Rights of the Terminally Ill Act – the first law in the world allowing assisted voluntary euthanasia. It was an early step in the changing way we viewed death.

Three days later, outside Edinburgh, a Finnish-Dorset crossbreed lamb came into the world. It was normal in every way other than being the first mammal cloned from an adult cell. Dolly would change forever how we saw life.

Neither was off to a smooth start. An effort to repeal the Northern Territory law was defeated locally, but the following year Canberra overturned it with the Euthanasia Laws Act 1997. These days voluntary assisted dying is legal in Victoria and Western Australia and will soon be in Tasmania.

Dolly effectively had three mothers: its DNA was taken from one ewe and then injected into the egg of another with a third carrying the embryo and giving birth. Its birth stunned scientists – and the world – not helped by risible reporting, even from some respected news outlets, referring to “Dr Frankenstein” and the possible misuse of cloning technology. This was exacerbated by US physicist Richard Seed who said he planned to clone a human being in advance of laws that would ban it.

Nonetheless, suddenly the promise of biotechnology and new treatments for old diseases seemed limitless. Minimalist American composer Steve Reich wrote a three-act opera starring Dolly, and the cheeky Scots voted for her as an alternative to the Queen.

Then Dolly died prematurely. Perhaps she had been born at the genetic age of her donors. Or was there a deeper flaw in the cloning process – might all cloned animals be similarly defect and doomed?

The answer was more prosaic. Dolly was normal, although, as a celebrity, she was often fed to perform for the camera, and she then became overweight and began stealing food from other sheep in her pen. For this she was isolated but quickly slimmed down. Also, she had developed arthritis, but that is often seen in middle-aged sheep. Dolly died short of seven years while the average life of sheep is about 10. The record is 28. Dolly was euthanised when it became clear that her lung cancer was advancing quickly. Neither is this uncommon in sheep and goats kept indoors; so she wasn’t stolen, Dolly had spent her entire life at the Roslin Institute at the University of Edinburgh.

Rendered lifelike by a taxidermist, she can still be seen at the National Museums Scotland. She was survived by five healthy offspring, all naturally conceived.

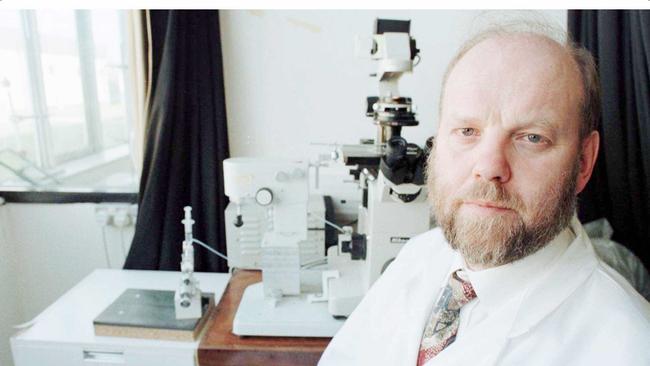

Since Dolly many other species have been cloned: dogs, cats, rats, ferrets, cows, camels and coyotes among them. Dolly was born of what is now viewed as a laborious technique called Somatic cell nuclear transfer. It was never that successful, indeed Dolly was the sole survivor from 277 attempts using cells from mammary glands – which is why she was named for country singer Dolly Parton. One of the scientists who led the team, Professor Sir Ian Wilmut, abandoned somatic cell nuclear transfer a few years later for a method pioneered in Japan that he believes will be more successful and socially acceptable (the creation and destruction of cloned human embryos has always been contentious). Wilmut, who still works at Edinburgh University, believes the Japanese method – in which human embryo stem cells might be created from skin cells – has the potential to lead to a range of treatments for Parkinson’s disease as well improved techniques for treating heart attacks and strokes.

So what did Dolly do for us?

One of the first people in the world to be told of her imminent arrival was the Melbourne-based scientist Alan Trounson, now Emeritus Professor at Monash University, who was hiking the hills above Edinburgh with his mate Wilmut in 1996 when Wilmut blurted it out.

“When he told me that I thought ‘that’s not possible’,” said Trounson this week. At the time Trounson was developing human embryonic stem cells.

“All the previous work in frogs and mice said you couldn’t do that, that an adult cell couldn’t be reprogrammed back into an egg and begin again. It was a major change in the way we think about biology and, hence, medicine. It was astonishing.”

Sir John Gurdon was first to clone an animal – a frog – in 1962. That was the year Shinya Yamanaka was born in Osaka. Fifty years later they shared a Nobel prize in medicine “for the discovery that mature cells can be reprogrammed”. They and Wilmut are all part of the great continuum of biological research and breakthroughs changing our world.

“Cloning is used through many of the animal industries,” explained Trounson. “The cattle industry used to be based on selling live bulls for breeding, and then it went over to artificial insemination, and now cattle sales are based mainly on embryos – cloned embryos.

“Almost all polo ponies are cloned, mostly out of Argentina. The camel racing industry in the Middle East is the same. The trade is no longer about selling the bull, but the multiple genetics of the sire.”

The next step is the development of stem cells that may help people with diseases such as Parkinson’s. “If you’ve got these cells you need to put in people’s brains you need to make sure that they don’t reject them,” said Trounson. “They have to be compatible. One way of being compatible is to make them from that person. I am using those types of cells – the Yamanaka cells – for treating (ovarian) cancer and it looks really, really good.”

And there is hope for some animals on the verge of extinction: “Now there a lot of tissue banks around the world that have kept the tissue from (endangered) species – we have one in Melbourne, called the Australian Frozen Zoo – which we set up a long time ago.”

Similarly, at the San Diego Zoo, researchers are trying to save the northern white rhino, only two females of which survive. “They have been able to collect eggs from the southern white rhino and they’ve used the nuclei from cells grown from the few northern white rhinos already lost and those which are left,” said Trounson.

The cloned embryo will be placed into a southern white rhino mother and hopefully the outcome is a species saved. “It’s a pretty major project, but is should work.”

Similar work is being done in Australia to reintroduce the southern gastric brooding frog that became extinct in the 1980s. “It’s beginning (the effort to preserve functionally extinct animals, but) it is not something that attracts a lot of money, but I think it will gather momentum.”

Trounson often ponders these remarkable developments. “Many things that I know now, I never thought possible – including Dolly.”

Did he ever say hello, Dolly? “I never met Dolly. She was just a sheep.”