1916, 1917 conscription referendums scarred Australia – will Indigenous voice to parliament do the same?

While the voice is the subject of heated invective for committed partisans on either side, most Australians are only just vaguely beginning to take notice. Coming from anyone else you might think this a bit of doom-mongering. A referendum? Triggering outbreaks of violence? Here?

Australian democracy is known for a few things – election day sausages, compulsory voting, the population’s disdain for the political class and the low temperature of political debate compared with that in similar nations. Spontaneous political violence isn’t one of them.

Still, Burgess is the head of ASIO. He would know. And it has happened at least once before. The most sustained public violence in response to political controversy since Australia federated in 1901 occurred a little more than 100 ago during the Great War. It centred on two national plebiscites held a little more than a year apart on the question of conscription – whether the government could compel men to enlist in the all-consuming global conflict.

There were riots, brawls and melees; mob assaults and counter-assaults, attacks on public speakers and prominent supporters. It was widespread, occurring in Rockhampton, Broken Hill, Hobart and Adelaide as well as the large metropolitan centres. In the 1916 campaign there were violent clashes between anti-conscription demonstrators and police at Broken Hill courthouse, and between police and soldiers in Queensland.

In the last weeks of the second referendum campaign in 1917, Yes speakers were assaulted at Bendigo and No speakers were driven off a stage stormed by returned soldiers near Belgrave.

In Brisbane a young pacifist woman was beaten by an enraged meeting of pro-conscription women. In Melbourne there were scenes of “wild disorder” that culminated in a mob brawl between returned soldiers and No campaigners that police waded into, using batons freely.

The most sustained public violence occurred at the MCG, where a crowd of 100,000 had gathered on a Monday evening to support Yes campaign speakers. Several thousand “antis” attacked the central stage, subjecting the platform to a fusillade of stones, rocks, broken bottles and – least threatening but most odious – a storm of eggs. Prime minister Billy Hughes and Melbourne’s mayor narrowly escaped injury but people nearby were less fortunate, in many cases needing hospitalisation. Later in the evening another brawl occurred, this time between returned soldiers and militant socialists at Flinders Street Station.

Those who complain of Australians’ lack of interest in politics could take 1916-17 as a cautionary tale. Here was maximum political engagement – no shortage of soaring idealism. Yet its ugly twin, seething partisan passion, was even more prominent. The two even seemed to feed on each other.

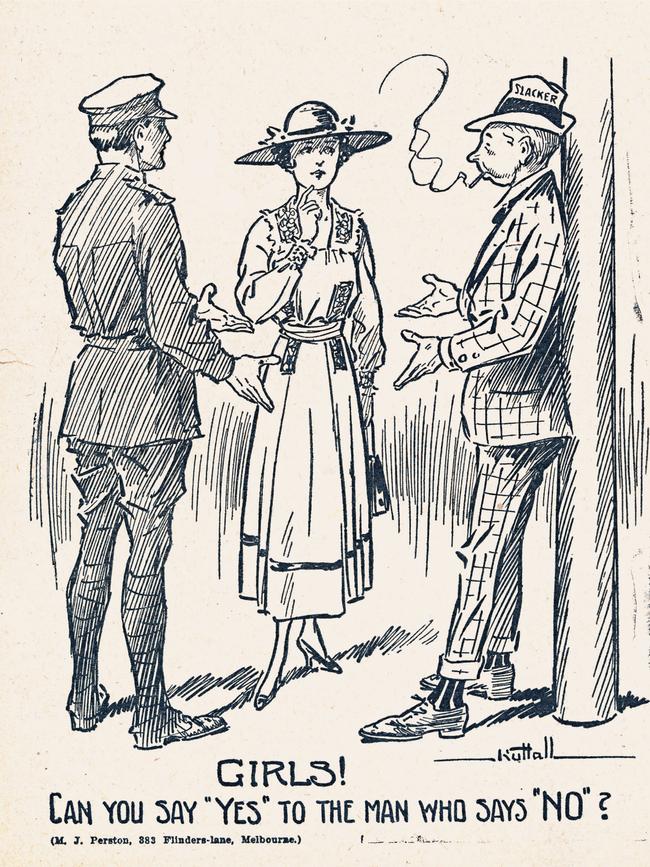

Voter turnout for both plebiscites was more than 80 per cent, startlingly high by pre-compulsory voting standards. There was a constant stream of political meetings in town halls, mechanics institutes, pubs and meeting halls, as well as outside on street corners and at football ovals. By one observer’s reckoning, the blizzard of pamphlets, leaflets, flyers and newspapers generated by the No side alone exceeded in quantity “any other downpour of printed matter in Australian history”.

From the vantage point of 2023, though, it is the public violence that marks the conscription plebiscites out in Australian political life, certainly among referendums. The referendum on whether to ban the Communist Party in 1951 or the republic question in 1999 – to take two of the more heated national votes as a point of contrast – inspired no shortage of inflammatory debate. But violence, spontaneous or otherwise, was almost totally absent. This has proved to be the abundant norm in a country that ordinarily keeps the wick of political passions burning low, enough for some to wonder if we’re not permanently asleep.

Every now and then, though – every 100 years or so by the looks of it – circumstances and latent social and cultural divides coincide with the implacable binary logic of a national plebiscite to ignite something far more dangerous. One hundred years ago it was the question of whether the state should compel men to go off and fight in a war. Now it’s the reorganisation of our system of government to give Indigenous Australians more purchase on government decision-making and the exercise of power. In their own way, each case becomes a force magnifier, putting pressure on deep, pre-existing social divides until, perhaps, explosion ensues.

Australians often think the roots of our political peacefulness lie in some traditional homogeneity; that has never been the case. The violence of 1916-17 reflected the rupturing of a hard-won consensus that had successfully managed the diversity of its parts. The consensus was hard-won because its parts consisted of large ethnic groups who were, historically and ancestrally, inveterate enemies. Scots, Irish, English and Welsh had more than a millennium of mutual distrust, conflict and loathing to reference when they came face-to-face with each other in Australia, often for the first time in their lives.

We celebrate diversity as a self-evident value but colonial Australians prized unity above all: in colonial idiom, diversity equalled division. The US had ghettos and more nuclear, sealed and separate ethnic migrant groups, but in Australia the intermarriage rates were high and shared residential zones were far more porous. The diversity was always present, a given.

What was most desperately needed were bridges to connect and unify. That was carefully managed. Every public school board and local charity organisation had to feature a representative from each of the big three: Scots, English and Irish. Crucially, no group on its own could claim an unchallengeable ascendancy. Sports clubs, friendly societies and the plethora of self-run, purposive associations that defined Australian life reflected a society where members of the largest religious and ethnic minority group, the Irish Catholics, weren’t contained within separate residential ghettos or confined to low economic and social status. Unlike Liverpool, New York or Belfast, they were everywhere. Next to you at work, at your local bowls club, alongside you at the public bar, as your next-door neighbour, soon enough inside your home as your son-in-law.

Before the great fracturing of the Great War, the Easter Rising in Dublin of 1916 and the subsequent Irish civil war, this was the dominant experience. And as you lived, worked, drank with and married each other, well, no wonder you had to rigorously police conversational taboo topics.

In Australia, more than elsewhere, you had to be a good mixer, without airs or special needs, able to rub along with others who may well disagree, and disagree strongly. The friendly affability that was the overt tone of Australian life required a tacit agreement not to stir up arguments or fan ancient hatred. The risks of social dispute were, in a perverse sort of way, greater than in the US, even though the actual level of dispute and violence was much higher there. But in the US ghettos and distinctive ethno-groupings kept potentially hostile groups apart and were accepted as normal.

The risks too were greater here than for Britain, with its centuries of vertical ties, patronage networks and class hierarchies cohabiting with common-law freedoms available to all. It was Australian social solidarity, which actively asserted egalitarian principles, that broke the mould. In what John Hirst called our “democracy of manners”, differences were elided through a mutual forbearance that treated them as if they didn’t exist.

How else could a nation built on traditionally fractious, warring religious sects and ethnic groups project itself into being and sustain itself once it had been achieved?

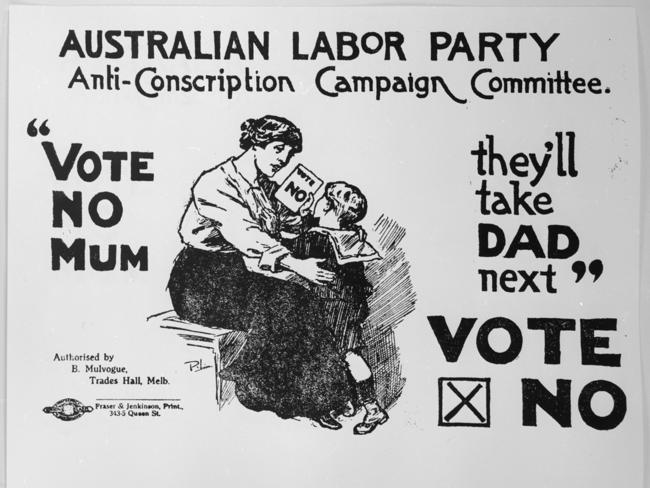

In 1916 and 1917, though, schism prevailed over solidarity. In the preceding years class divisions were becoming more central to people’s sense of identity. Irish Catholics were gravitating to the recently established working-class party, the Australian Labor Party. But it was the conscription plebiscites, and the toxic antagonisms it unleashed, that destroyed any chance of sustaining a shared vision, a common identity and an appreciation of the common ground that all could meet upon.

And today? Culture and technology have generated a new tribalisation of identity and eroded the shared vision of who we are. There are few overlapping cleavages where people with different viewpoints and principles are encountered close up in everyday life.

Instead, echo chambers of furious agreement and mutual loathing predominate alongside large swaths of public life cloaked in total silence, where the fear of social and professional punishment for expressing different views imposes torturous brands of self-censorship.

The fallout from the 1916 and 1917 plebiscites scarred Australia for a generation. Against all expectation, and against an almost totally unified cohort of elites, institutions and cultural leaders, the No side won. The labour movement, energised to the point of incandescent, having divested itself of the parliamentary moderates, in loose alliance with some Catholic leaders, prevailed.

But in the poisoned atmosphere of bitter aftermath the victors suffered worst. The ALP split along ethnic-sectarian lines and spent most of the next 25 years in the political wilderness. Irish Australians, meanwhile, retreated more and more into their own cultural huddle.

The plebiscites worsened all the divides the war had already made uncomfortably apparent – class, ethnic and sectarian, political and ideological. It stands as a stark warning of today’s dangers. There are no real victors if we lose the shared vision, the common ideals and principle that have defined the Australian achievement. In 1916-17, both sides reaped a classic bitter harvest. So also in our time, when “spontaneous violence” in a referendum campaign again looms as a real prospect, we would do well to remember that whatever the outcome of this national vote, we’re going to have to live with it – and live with each other – for a long time to come.

Alex McDermott is a historian and writer based in Melbourne.

When the head of ASIO warns Senate estimates of the chances of “spontaneous violence” occurring as a result of the heated debate surrounding the voice to parliament referendum, as Mike Burgess did recently, you can be forgiven for sitting up.