Gough Whitlam’s relationship with The Australian built on personalities

TO describe the relationship between The Australian and Gough Whitlam at the height of his political powers as hot and cold is an understatement.

TO describe the relationship between The Australian and Gough Whitlam at the height of his political powers as hot and cold is an understatement. It was more like a fervid embrace turning into a frozen and bitter divorce.

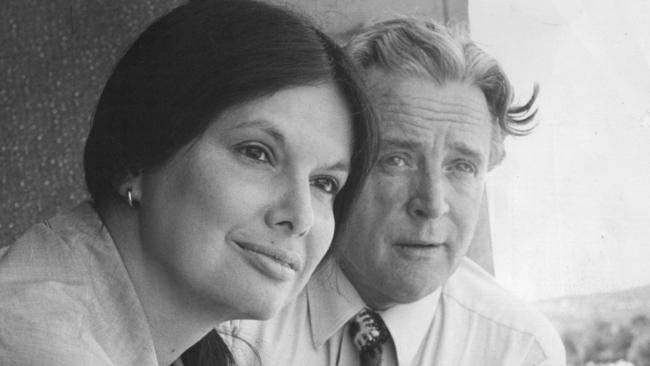

The relationship was multifaceted and, inevitably, built on personalities. The Australian’s proprietor Rupert Murdoch gave unstinting support behind the scenes and in editorials during Whitlam’s triumphant 1972 “Its Time” election campaign.

He was rewarded by Whitlam’s rejection, laced with studied disdain. But if Murdoch felt aggrieved by Whitlam’s personal rebuffs his response was at arm’s length, through editorials increasingly critical of Whitlam’s government.

By the time of The Dismissal in November 1975 The Australian had become a key player in the political joust of the century. It repeatedly advocated the course of action ultimately decided on by Governor-General, Sir John Kerr — the dismissal of Whitlam’s government and its replacement by caretaker Malcolm Fraser.

These events, hashed and rehashed over nearly four decades, today take on a starkness that was not apparent at the time. The reminiscences of those at the centre of the events have implied motives that were then absent from public discussion or nderstanding.

Rupert Murdoch established The Australian in 1964 with a liberal voice on social policy. Through the 60s he became increasingly disenchanted with the turgid conservatism of Liberal prime ministers Menzies, Holt, Gorton and McMahon and by 1972 had swung his support solidly behind Whitlam.

This was seen in editorials, but behind the scenes Murdoch was also showing trademark activity. He suggested policy initiatives, wrote speeches and paid for ALP-aligned advertising to appear in rival publications. He later assessed the value of his contribution at $75,000 — a considerable sum in those days.

Eric Walsh, a former political reporter for Murdoch’s Daily Mirror who became Whitlam’s press secretary in government, recalls in material provided for The Australian’s 50th “the Whitlam-Murdoch relationship was never to become a close one.”

“While Murdoch, in the manner of newspaper barons the world over, found it necessary, comfortable and therefore easy to occupy a place close to a political leadership throne, the extremely proper Whitlam seemed anxious not to be, or appear to be, beholden to any outside influence regardless of any past political favours,” Walsh says.

“Rupert, he was determined, would remain at arm’s length.”

Walsh says Murdoch sought government concessions relating to an alumina mining venture in Western Australia, but Whitlam refused.

“Rupert then canvassed the idea that he might be made Australian High Commissioner in his new home country, Britain,” Walsh says. “He would, he said, put his commercial interests in the UK, not as extensive then as they are today, in some sort of blind trust. Gough again failed to act. Where no doubt he had acted with admirable propriety in his refusals, they had been done with perhaps a tactless anniversary that despite the “super effort” provided for Labor, bluntness with no attempt at all to offer to his benefactor some explanation.”

This bluntness became pointed personal rejection when Whitlam twice cancelled dinner appointments with Murdoch. Walsh, keen to keep Murdoch as an ally “knowing how useful he might be in the future,” saw these rebuffs as the final opportunity to preserve a beneficial relationship.

The Australian’s editorials certainly moderated from support to neutrality during Whitlam’s first term, but there was never any mention of personal dynamics or animosity. During the snap 1974 election The Australian sat on the fence, endorsing neither side, as Whitlam was re-elected.

As the second Whitlam government became increasingly dysfunctional, the criticism increased. The loans affair, the hidden romance between Jim Cairns and Junie Morosi and the Opposition’s refusal to pass the Budget of 1975 provided fertile grounds for criticism. Under editors Les Hollings and Bruce Rothwell the leading articles pounded Whitlam. After The Dismissal journalists complained the paper was exhibiting deliberate and blatant editorial bias and went on strike during the election campaign.

This period of supercharged political passions undoubtedly damaged The Australian in the eyes of many of its readers, but for the public it was largely a sideshow.

Malcolm Fraser won the election in a landslide. Whitlam retained the leadership of the ALP, even after renewed assaults over secret negotiations to use Iraqi petro dollars to fund future campaigns. He fought another campaign in December 1977 but lost heavily again. The leadership and the job of rebuilding a fractured Labor Party passed to Bill Hayden and Whitlam resigned from parliament — and politics — early in 1978.

Whitlam and his supporters saw The Australian as ruthless and partisan.

The Australian’s editorial writers saw Whitlam and his government as an incompetent rabble.

But nearly 40 years on Whitlam’s achievements are remembered more than his political battles.