US President Donald Trump’s missile strike against Syria’s Shayrat air base last week, responding to the chemical attack on Khan Sheikhoun in northern Idlib province, garnered cautious praise across the political spectrum. It also highlighted the complex choices facing the US, allies such as Australia, regional players like Turkey and Iraq, and institutions such as the UN.

The key to understanding the strike, though, lies in a question that’s been somewhat overlooked: why did Bashar al-Assad’s regime need to use the nerve agent in the first place?

We should start by noting that praise for the strike can largely be explained by the extraordinarily low expectations Trump and his predecessor set for effective action on Syria. Trump’s alleged Russia ties, praise for strongmen, positive statements about Assad until days before the attack, and expressed disdain for world opinion set the bar so low that he got credit just for upholding an international norm against chemical weapons, and showing he was prepared to go up against Moscow.

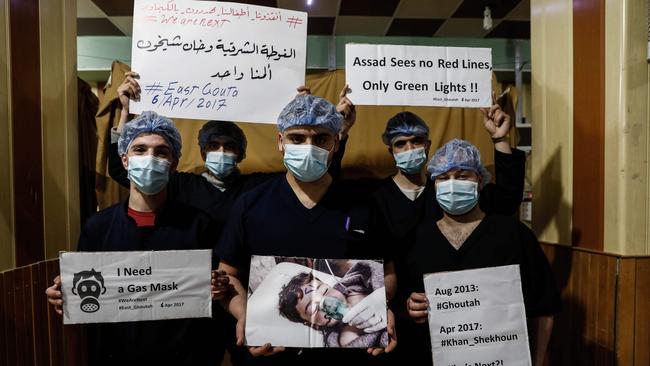

His prompt response also contrasted with president Barack Obama’s failure to enforce his own “red line” after the vastly more lethal Ghouta attack of September 2013, which killed 1500 and poisoned thousands (the Khan Sheikhoun attack killed 74). When Obama called his own bluff on the red line, ceded the diplomatic initiative to Moscow and put the Kremlin in the driver’s seat for negotiations on Syria, he enabled a Russian-brokered agreement on Syria’s chemical stockpile that bolstered the regime’s legitimacy.

Far from eliminating Syria’s chemical weapons — as former national security adviser Susan Rice repeatedly claimed — that agreement left Assad’s regime with reduced but still lethal capability, including extensive supplies of chlorine gas and smaller stocks of nerve agent that it used in later attacks. As Syrians told me after Ghouta, they felt the White House was telling Assad he could go ahead and massacre his own people, provided he did it with barrel bombs and artillery rather than chemicals.

The failure to act after Ghouta so appalled some members of Obama’s cabinet that Democratic “Syria hawks” (including former secretary of state John Kerry) came out in support of last week’s Shayrat strike. Given the continued refusal by many on the left to recognise Trump as America’s duly elected President, this speaks volumes for the level of bipartisan support for decisive action on Syria.

It also highlights the comfort of many progressive interventionists (including Kerry, but also Hillary Clinton) with unilateral American use of force — provided it is sanctified by humanitarian principles such as “responsibility to protect”. All this put Trump’s punitive strike in the political mainstream, making him look positively, well, Clintonian.

The Western narrative on Assad — reinforced just this week by presidential spokesman Sean Spicer — has been that his regime is uniquely evil, uses chemical weapons simply because it can, hates its own people and just wants to burn the country to the ground.

But, in fact, Syrian use of chemical weapons in the war so far has been highly calculated and strategic. Assad’s regime, far from being blind to international condemnation, understands the severe political consequences of using chemical weapons, and only does so when its back is against the wall. Assad’s regime has shown no compunction in using nerve agents when its survival is at stake, but otherwise it mostly keeps chemical weapons as a hip-pocket emergency reserve that can be rapidly deployed when manpower is short.

Thus, the real missed opportunity of 2013 lay in a failure to understand the regime’s motive in using chemical weapons: as a last resort, when a victorious coalition of mostly secular rebel groups was threatening the eastern suburbs of Damascus, making significant gains in the regime’s heartland and jeopardising its survival. Decisive action, combining the measured use of force with a strong diplomatic push, could have forced Assad — given the dire pressure he was under — into genuine peace talks.

The Ghouta attack was not an act of unthinking evil but one of calculated desperation, and strikes against regime positions could have not only punished Assad for his use of gas, but enabled a rebel advance into Damascus that would have opened a path to negotiations. The diplomatic price for suspending air strikes would have been regime concessions in UN-led peace talks, while the international community would have retained the ability to restart strikes at any time, or impose no-fly zones to enable humanitarian corridors to protect the people.

This, in fact, was the argument that allied airpower experts made at the time, likening the situation to the NATO-led bombing in the Balkans that ended the Bosnian war, led to the Dayton Accords and halted massacres in Kosovo in 1999.

This isn’t as far-fetched as it seems. Remember, 2013 was before Islamic State emerged, before its blitzkrieg dramatically changed the game in Iraq, before the declaration of the caliphate prompted a spike in world terrorism, before Turkey’s military incursions into Iraq and Syria, and before the European immigration crisis.

In 2013, the dominant Syrian rebel factions still included secular groups, while jihadists were on the back foot. This was also before Russia’s intervention improved Syrian air defences and complicated targeting by putting Russians on to key regime sites, and before the presence of more than 1500 Western ground troops in Syria made it possible for the regime to easily retaliate. And it was before the Iranian nuclear deal of 2015 brought a flood of funds, advisers and troops from Tehran to further bolster the regime.

Against this background, last week’s strike seems almost laughably symbolic: 60-odd Tomahawk cruise missiles, launched from two US navy ships in the Mediterranean, with allied aircraft kept away from Syrian air defences, and the Russians (and thus, presumably, their Syrian proteges) given plenty of warning to get out of the way. The missiles destroyed some obsolete aircraft, killed a few regime troops, and left the airfield at Shayrat so lightly damaged that the regime was using it again within hours, even launching a further strike from Shayrat (with conventional munitions) against Khan Sheikhoun the very next day.

Kosovo 1999 it was not. But again, the key question is why Assad’s forces felt the need to use the nerve agent in the first place.

Khan Sheikhoun is a town of 50,000 on the southern edge of Idlib, a province in northwestern Syria that abuts Turkey to the north, Aleppo to the east, and Hama and Latakia provinces to the south and west. As of mid-April, apart from tiny regime enclaves at Fua and Kefraya, Idlib is almost totally controlled by a jihadist coalition led by al-Qa’ida’s Syrian affiliate Jabhat Fatah al-Sham, still widely known by its former name, the Nusra Front.

Nusra detests Islamic State (a feeling Abubakr al-Baghdadi’s organisation heartily reciprocates). But in many ways it poses a much more severe threat to the regime than Baghdadi’s group. The Nusra-led offensive in Idlib and Hama has been under-reported, but for Syrians it’s the most important event of 2017 so far.

Even as the regime recaptured Aleppo in December 2016 — with heavy support from Russian airstrikes, Russian special forces, Iranian advisers and Hezbollah militia — Nusra and other groups formed an alliance, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, to recapture ground from Assad’s forces.

After weeks of preparation they launched a major offensive on March 21 with more than 5000 well-armed and well-organised fighters from seven rebel groups operating under Nusra leader Abu Mohammed al-Jolani. Tahrir al-Sham gathered the most capable rebel groups in Syria into a single coalition under al-Qa’ida’s leadership, pointed them directly at the regime’s weakest point and achieved immediate success.

Within days, rebel fighters pushed to within 5km of the Hama suburbs, threatening the regime’s control of a critical city that anchors its northern flank and provides access to Aleppo. They also made significant gains into the al-Ghab plain, Syria’s breadbasket, an area essential to the regime’s ability to feed Syria’s pro-government population.

Nusra’s rapid advance jeopardised Assad’s control of the economically and politically important Hama and Latakia provinces, and posed a risk to Russia’s naval and air bases to the south.

Khan Sheikhoun now sits at the base of a rebel salient that stretches from Idlib south into the outskirts of Hama city, and west into al-Ghab. As I write, this salient is being counter-attacked all along its perimeter by regime forces desperate to stem the Nusra advance, but lacking the manpower or ground-based firepower to roll back the rebels. Knocking out Khan Sheikhoun from the air would immediately collapse the rebel salient, letting the regime stabilise the front line. Unsurprisingly, doing exactly that has become a major priority for Assad.

The town’s importance was underlined by the fact that the pilot who allegedly carried out the sarin attack was Major General Mohammed Hazzouri, a Syrian air force officer commanding the 50th Air Brigade at Shayrat, and whose family name suggests he’s related to Mohammed Abdullah al-Hazzouri, governor of Hama, who was appointed by Assad in November 2016. Obviously, when you launch a gas attack using a fighter jet flown by a two-star general from the same prominent family as the provincial governor, you’re telegraphing that this is a pretty serious priority.

In fact, the town has been heavily attacked by regime forces (including earlier attacks with chemical weapons late last year and again last month) and subjected to multiple air strikes and artillery bombardments as the regime tries to contain the threat to its northern flank. Assad’s reliance on artillery and aircraft underlines his lack of ground assets: despite Russian, Iranian and Hezbollah support, his forces have their hands full consolidating control over Aleppo, trying to relieve the isolated city of Deir Ezzor in eastern Syria, and fighting on the southern front against other rebel groups.

All this indicates that the regime is again under serious pressure, that its position is far shakier than its propaganda narrative after the recapture of Aleppo might suggest, and that firm pressure now might bring renewed progress toward peace talks. But the situation today is vastly more complicated than in 2013. There are real risks to allied aircraft over Syria from Russian and Syrian air defences, and to special forces and conventional troops (there are now, according to media reporting, as many as 1500 rangers, marines and special forces on the ground in Syria) in the event of strikes against the regime.

The rebels opposing Assad today are not the largely secular forces of 2013 but rather are dominated by al-Qa’ida, while Russia has indicated it plans to further improve Syria’s air defences and has vetoed efforts in the UN for further talks on a Syrian peace deal.

To think that, under these circumstances, mere words — Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s frosty visit to Moscow, Trump’s call for Vladimir Putin to stop covering for Assad, or ambassador Nikki Haley’s fiery confrontation with Russian diplomats at the UN — will force Putin to back away from a critical strategic relationship going back to the 1960s, or force Assad to stop throwing everything at an attack that threatens his survival, is fantasy. If the Shayrat strike is to be more than the latest useless symbolic gesture, it needs to be followed by a fundamental change in strategy.

Until a week ago, Trump’s Syria policy was to downplay any call for regime change, acquiesce in the permanence of Assad’s regime and collaborate with Putin against Islamic State. As recently as April 5, the day after the Khan Sheikhoun attack, Tillerson was asserting that Assad was here to stay.

This was bad policy: not just on moral or political grounds (Assad has killed 10 times as many Syrians as Islamic State, and most US partners both inside Syria and throughout the region see removing Assad and ending the war as the top priority bar none) but also in practical military terms.

Assad lacks the military capacity to stabilise Syria: he’s losing ground in key areas, controls less than 23 per cent of the country, has no prospect of reunifying Syria, presides over a patchwork of local militias and thuggish warlords with purely nominal allegiance to his government, and couldn’t survive six months without external support.

The use of sarin gas underlines how desperate his situation is. Even if it were morally and politically possible to work with his regime for the greater goal of destroying Islamic State, the man simply can’t do the job.

More fundamentally, the goal of destroying Islamic State may not actually be the higher strategic priority, at least not in Syria. Unlike Iraq, where recapturing Mosul and crushing the caliphate is a key first step toward stabilising the country, in Syria the greatest threat to stability is Assad himself.

For most Syrians I’ve spoken to, the idea that anyone engaged in the uprising since 2011 would sit down again under Assad is ludicrous, and many have told me the biggest winner so far isn’t Islamic State but al-Qa’ida, through its Nusra affiliate.

From a wider strategic standpoint, the other key audiences for the Shayrat strike were Chinese leader Xi Jinping (who was dining with Trump as the strike went in) and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un. Using the Syria strike to telegraph a zero-tolerance policy for weapons of mass destruction, administration spokesmen talked of a new joint effort with China to rein in North Korea’s nuclear adventurism. For a President who spoke blithely on the campaign trail about Japan and South Korea acquiring their own nuclear weapons to deal with Pyongyang, this represents a big step forward.

More importantly, the move of the USS Carl Vinson aircraft carrier battle group toward Korean waters to deter further missile launches, and the deployment of US air defence systems and special operators in South Korea, showed this was not just talk.

The choices facing President Trump on Syria today are vastly more complex than those president Obama failed to deal with in 2013. But his change of policy after the Khan Sheikhoun attack — perhaps prompted by the presence in his inner circle of experienced strategists such as Secretary of Defence James Mattis and National Security Adviser HR McMaster — shows he’s at least capable of learning and adapting.

Along with the change on Syria policy and the move to deter North Korea, last week’s strike was rapidly followed by shifts in Trump’s tone on China (evidently no longer a currency manipulator), NATO (apparently no longer obsolete) and Russia (it would have been nice to co-operate, but that’s not possible while Russia continues to back Assad). Don’t look now, but all this seems to be pushing the Trump presidency back toward something resembling relatively mainstream US policy in the tradition of presidents Bush, Clinton and Reagan.

Whether you think that’s good or bad probably depends on your view of America’s role in the world, and the longstanding propensity of US leaders to use unilateral military force. But symbolic as it was, the Shayrat missile strike may also open the door to new thinking on Syria — and after six years, half a million dead, dozens of cities destroyed and millions displaced, that can only be a good thing.

David Kilcullen is a former lieutenant-colonel in the Australian Army and was a senior adviser to US general David Petraeus in 2007-08, when he helped to design the Iraq war coalition troop surge. He also was a special adviser for counterinsurgency to former US secretary of state Condoleezza Rice. He is the author of Blood Year: Islamic State and the Failures of the War on Terror (Black Inc).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout