Ballarat’s children: dirty secrets hidden in the confession box

Information gleaned from unknowing parishioners was used by pedophile priests to plan and carry out their crimes.

The Sacrament of Penance, better known as the Rite of Confession within the Roman Catholic Church, is a ritual many non-Catholics find bemusing. It is fertile ground for sketch comedy and often features in movies as a plot device. A man enters, slides the screen across to reveal a murky figure on the other side.

The Rite of Confession raises all manner of legal and ethical dilemmas and conflicts between Canon Law and the law of the land. If a priest hears a confession from a person who confesses to planning to commit a murder at some point in future, is the priest bound by law to report to the police? If a priest takes confession from a man who has committed serious crimes and the priest does not inform the police, can the priest be charged with offences such as being an accessory or conspiracy?

The answer is grey and uncertain and police and prosecutors inevitably give it a wide berth. A priest cannot be compelled to give evidence in a trial based on admissions made in the confession box in any Australian jurisdiction.

There have been times when the royal commissioners have alluded to confession as offensive to non-Catholics, that one person can be absolved of guilt for a crime due to his or her faith while those of other or no religious persuasion cannot.

This is indicative of a potentially dangerous overreach. We are yet to learn if the royal commission is considering recommendations seeking law reform to require priests to give evidence in a courtroom based on admissions made in the confession box. The state has no place interfering with religious ceremonies and rituals and any attempt to reform law in this regard is highly contentious

But the door swings both ways.

How did the Catholic Church within the Ballarat Diocese use the Rite of Confession to help its offending priests from avoiding the clutches of the law?

When the disgraced priest Paul David Ryan gave evidence in a private hearing at the royal Commission, Ryan acknowledged he began grooming an adolescent male who had offered up intimate secrets about his own sexuality during confessional.

The are stories Gerald Ridsdale raped a boy in the confession box in Ballarat. One victim of clerical abuse in Ballarat who began going to confession when he was aged 12, remembers whenever he entered the confessional the first question he was invariably asked related to his sexuality. One other victim recalled a priest masturbating during confession.

The Rite of Confession has been open to abuse throughout the Ballarat Diocese and elsewhere. It is a form of social control. Those who follow the sacrament leave their secrets with a priest and walk away cleansed of guilt and remorse. That means the priest has become a repository for every piece of gossip and story of malfeasance in the community. In the case of Mildura and Ballarat, it often meant leaving intimate details with men who had much darker and more horrible secrets to keep hidden.

For a period in the late 1960s in Mildura, a Catholic parishioner could find John Day and Gerald Ridsdale listening intently to their confessions. Day was an exalted cleric who became a Monsignor in the Church, Ridsdale a perpetual embarrassment who was shanghaied around the diocese whenever complaints from parishioners became too loud.

Let’s make no mistake, these men stand as two of the worst criminals this country has seen; notorious child sex offenders whose victims number in the hundreds. Yet Day and Ridsdale took confessions from unknowing parishioners, from adults and children and used the information for the furtherance of their criminal activities.

When writing the book, Unholy Trinity, I discovered Day routinely used information gleaned during confessions against his own parishioners. Troops of children would be marched through to the Sacred Heart Church from the adjoining primary and secondary schools. Little kids as young as eight, trembling with fear would enter the confession boxes and cough up their sins.

What great sin an eight-year-old could commit was not countenanced but some would admit to stealing oranges from an orchard or a soft drink from one of the footy club canteens. Day would reassure them their sins had been absolved and they were encouraged to walk away free from burden.

Day would inform his partner-in-crime, Detective Sergeant Jim Barritt. Barritt would then visit the children’s homes, drag them away and charge them. In all the cases I am aware of no convictions were recorded but the children felt the ignominy of being put through the courts. For some it began a life of difficulties with police while the remainder were taught a harsh lesson and lost all trust in authority.

Similarly, Barritt was able to use information provided by Day to his advantage. This bent cop, as corrupt as any copper I’ve come across, was also providing information to ASIO in the 1960s in reports he knocked together at Mildura police Station in late night typing flurries.

It was all part of a racket that allowed Day to commit crimes against children while Barritt was able to boast high arrest rates, even though the matters were often trifling.

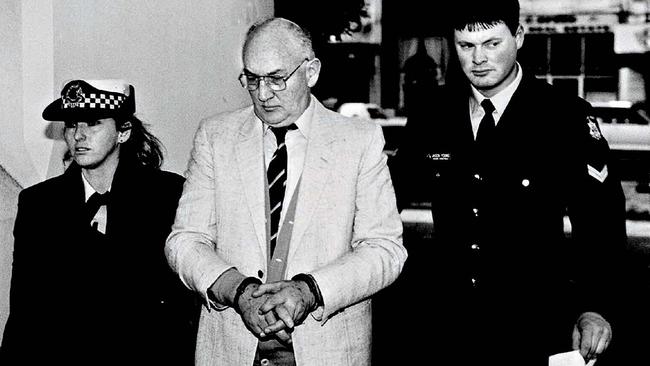

The bigger question is who took John Day’s confession? Who took Gerald Ridsdale’s? Who took the confessions of Bob Claffey, the morbidly obese Ballarat priest who was sentenced this month to 18 years in prison for raping and indecently assaulting over thirty years, including a vicious attack on a seven-year-old girl in 1969?

If Day, Ridsdale, Claffey or one of the raft priests and clerics subsequently convicted of child sexual abuse made admissions in the confession box, why was no action taken at the time? Why were police not informed?

There is an open and direct conflict between Canon Law and the law of the land. It seems even in the appalling business of child sexual abuse, Ballarat’s clerics believed their law held sway.

The Church and its officers must assume a broader responsibility beyond protecting their own. If they hear of child sexual abuse regardless of how, when and where, they must report it.

The lesson of Ballarat is, if paedophilia goes unreported it flourishes and the numbers of victims quickly escalates.