Why bother reading, when you can watch culture go by

English literature is dying as university students flock to science and technology courses. But in the age of AI we need culture more than ever.

On a grey day, the campus of the University of Warwick has the appearance of a benign North Korea. It’s something to do with the too-wide communal spaces, the huge institutional buildings and the heavy sky.

Christopher Tang, who is studying English literature and creative writing, shows me around the university’s arts centre. A cinema, a concert hall, a crowd of frantic students printing off essays from the communal printers. The inexpert janglings of Warwick’s amateur pianists emanate from the practice rooms upstairs.

University artistic life seems to be proceding as normal, but there are shadows of unease. Tang is the author of a lucid essay for the student newspaper, The Tab, which lamented the rise of a science-worshipping campus environment in which “English literature degrees are constantly demeaned and degraded”.

And, indeed, his generation of English literature undergraduates is studying in the midst of an unprecedented crisis in the humanities. The number of degrees awarded in history and history of art have fallen by almost a third in a decade. Degrees in foreign languages declined by almost 40 per cent in the same period. In 2021, 14 British universities accepted “virtually no” students to study any foreign language.

The decline of English studies is most striking. A decade ago English was the most popular A-level. Today it is no longer in the top ten, outranked by the likes of sociology, psychology and business studies. Between 2011 and 2021, the number of students studying English at university fell by a third. The subject is, in the view of one Russell Group academic, experiencing “a rapid, almost terminal decline”.

Universities cancel their English degrees almost annually. Last year Sheffield Hallam did so; the year before it was Cumbria. Even well-established institutions are threatened. Birkbeck University, founded in 1821, is home to one of the most renowned English departments in the country. Last year the university announced plans to fire half that department’s staff.

Among lecturers a mood of despair is taking hold. “It would make you weep,” one senior academic tells me. The number of undergraduates studying English literature at her university has fallen from about 200 ten years ago to 30 today. “Everyone’s worrying about student numbers,” another lecturer in English tells me. The mood in his department is “hysterical”.

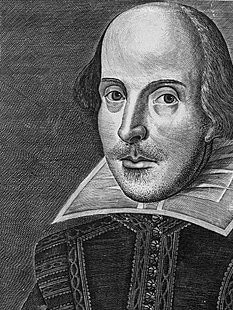

The decline in English literature is most shocking because the subject was so prestigious for so long and because literature is so central to Britain’s cultural self-image. If the British genius has expressed itself comparatively rarely in the arts of musical composition or painting, we are able to boast perhaps the richest literary tradition in the world as the land of Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton and Dickens. Now we face not only a crisis of arts education but of cultural identity. What is a Britain in which nobody reads Shakespeare or Dickens?

The great modern flowering of the humanities took place in the decades after the Second World War. Ambitious students, paying no fees, flocked to new “plate glass” universities such as Sussex, York and Lancaster where they took possession of the prestigious cultural knowledge that had once been the preserve of a tiny social elite. “Like homing pigeons, to a loft we knew only from hearsay, we headed for the humanities and above all for literature,” remembered the critic Richard Hoggart, a working-class grammar school boy who won a scholarship to Leeds University. The optimism of that time is preserved in Kenneth Clark’s 1969 television program Civilisation, a sweeping survey of the history of Western culture. The last episode featured the concrete ziggurats of the newly opened University of East Anglia set to a soundtrack of ecstatic choral music. Culture, Lord Clark reassured viewers, was in the safest possible hands: “I should doubt if so many people have been as well read, as bright minded and as critical as the young are today.”

A cultural education was held to be spiritually, morally and even politically improving. In his book The Liberal Imagination, a bestseller in 1950, the American critic Lionel Trilling argued that literary study cultivated a sympathy for the individual that was essential to the flourishing of a liberal society – a vaccine against the inhumanity of ideology. “Literature,” Trilling wrote, “is the human activity that takes fullest and most precise account of variousness, possibility, complexity and difficulty.”

Students responded to this mood of idealism. In 1967, 86 per cent of new undergraduates listed “developing a meaningful philosophy of life” as a “very important” or “essential” personal goal. Today, claims for spiritual or moral virtues of the humanities are just so much rhetorical garnish - an addendum to the anxious reassurance that English offers commercially valuable “transferable skills” such as critical thinking. A vindictive mood of Gradgrindian rationality prevails. When the government announced last year that universities offering “low-value” degrees would be financially penalised, there was no question that “low value” referred to “value for money”, not “value for the soul”.

Almost all the academics I speak to mention the coalition government’s decision to increase tuition fees to pounds 9,000 a year in 2010 as a turning point. Modern teenagers are faced with the second most expensive degrees in the world after the United States. Student loan repayments mean a graduate earning more than pounds 26,575 a year faces an effective marginal tax rate of 41 per cent. For those earning pounds 50,000 a year it climbs to 51 per cent. Confronting these punishing conditions, as well as extortionate rents and falling living standards, students have flocked to the perceived economic safe havens of Stem subjects (science, technology, engineering and maths).

However, as Hetan Shah, the chief executive of the arts charity The British Academy, points out, the assumption that sciences are vastly more profitable is false. In Britain, humanities and social science graduates earn pounds 35,360 a year on average and graduates of Stem subjects pounds 38,272. “We have a slightly misplaced view of what our economy is like,” says Shah. “We’re a services economy. We’re not Germany.” Creative industries make up 6 per cent of the British economy. The rise of artificial intelligence systems such as ChatGPT threatens not only writers and artists but also coders. Some careers that require mathematical skills “will be mopped up quite fast by AI”, he says. “Employers are increasingly looking for critical and creative thinking.” Harry Shum, a senior AI researcher at Microsoft, has written that, “as computers behave more like humans, the social sciences and humanities will become even more important”.

The decline of the humanities is a worldwide story. Student numbers have dropped equally dramatically in the US. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, four fifths of its member countries report falling enrolment in arts subjects. The common factor is the technological revolution precipitated by the launch of the iPhone in 2008. Ever since, books have had to compete with ubiquitous digital distractions. A 2020 study found a “sharp decline” in reading. More than half of British adults

say they haven’t read a single book in the past year.

Academics agree that the past ten years have seen a decline in their students’ capacity to engage with long texts. Many arrive at university having never studied whole novels or plays at school, only extracts or scenes. One university head of department tells me: “I used to expect students to easily read a novel in a week and I just can’t expect that any more.” The impossibility of getting students to concentrate means classic novels are falling off syllabuses. “We used to teach Middlemarch. We don’t any more,” she says. “There was a time when I used to attempt to teach Ulysses. Now I just don’t bother.” Recently she’s been teaching Ralph Ellison’s 600-page classic of African-American literature Invisible Man but, “I can guarantee not one of my students will have finished it.”

A young academic who teaches English at Bristol University, says: “It’s not true that everything is getting worse and everyone is dumber than they used to be. But what is the case is that we are less a reading culture than a watching culture. Students are more interested in Netflix series than the traditional literary canon.” It is now common for lecturers to introduce a book with a film adaptation to make it seem “less forbidding for students” for whom the novel increasingly seems a “rarefied form”. But can adaptations aid the study of literature? Think how different ITV’s current adaptation of Tom Jones is from Henry Fielding’s 18th century novel. Another academic says she has given up delivering hour-long lectures. Students can only deal with 20-minute chunks.

Even the students themselves agree with this pessimistic assessment. Over coffee in the Warwick campus’s bustling Pret a Manger, Tang says: “The rise of social media has definitely affected the way I read things. My attention span has gone downhill ever since I’ve been on TikTok.” Tang speaks enthusiastically about Ocean Vuong, James Baldwin and Sylvia Plath but tells me that he finds “the traditional parts of my degree” such as “medieval and renaissance literature” to be “the most boring”. He opted out of the modules on Victorian fiction. Were they popular, I ask. “No.” He laughs apologetically at my expression of despair. “Everyone hated it.”

To those who spent their teens online, literature seems much less culturally central and prestigious than it did even 20 years ago. It is no longer obvious to many students that novels and poetry should be singled out for exhaustive study. Tang says his favourite projects included an essay on the Netflix superhero show The Boys and a study of a video poem. Another Warwick student, Oscar, tells me that “literature isn’t just books - if you study theatre there’s no reason why you shouldn’t study TV”. Their professors are thinking along the same lines. Stephen Greenblatt, the doyen of Renaissance studies, recently told The New Yorker that more English departments should think about teaching television shows such as The Wire and Chernobyl.

To many conservatives, such developments would doubtless confirm an impression of arts degrees as the new Mickey Mouse subjects: intellectually soft and economically irrelevant. But there is also a new hostility to the humanities from the left. Among progressives, once important guardians of high culture against the philistinism of consumer capitalism, there is a mood of suspicion towards the heroes of the Western canon, founded on their implication in the racist and sexist societies of their time. Visitors to art galleries will be familiar with the genre of censorious picture captions which effortfully associate even the most blameless of watercolourists with the historical sins of empire. Whatever useful political idealism such signage inspires, it risks damaging the prestige of the humanities. In the 1960s, culture was associated with elite status as well as spiritual and moral improvement. Many modern students must wonder: where is the glamour in studying the work of dead gammons?

One young academic working at a prestigious Russell Group university worries about the “Americanisation of the British academy” and the ensuing politicisation of literature. He says that to secure funding it’s helpful to link one’s research to a fashionable political theme, such as gender, the environment or the currently popular trend for “digital humanities”. The problem, he says, is that “it’s always literature and something [the environment, racism, gender]. It’s always the thing that literature is attached to that’s carrying the value.”

Though anathema to traditionalists, a more politically aware approach to literature has many student advocates. Oscar tells me he finds his course off-puttingly “occidental”. A degree in only “English” literature strikes him as pointlessly limited. “I’m not saying that English isn’t wonderful but there’s so much more out there. I think it’s crazy that English literature is still used as a title for a degree when ‘comparative’ literature works just as well, or just ‘literature’.”

One academic I spoke to fears that the fashionable new emphasis on politics leads to a dead end. “Literary academics have ceded a fundamental principle and tried to redescribe literary scholarship as a form of political activism.” The problem is that “in a world where the reading public is slowly diminishing, any political activism that is founded on the study of literary texts is wishing itself into irrelevance. Why study literature if you can just study politics?”

The decline in the humanities is not felt by all universities equally. Academics at Oxford and Cambridge have noticed little change in the quality or quantity of their students. Seamus Perry, formerly head of Oxford’s English faculty, says English applications have dipped from just over 1,000 ten years ago to just under 1,000 today, a statistically insignificant change. His students are “as engaged, clever and sparky as they always have been”. Dickens is perhaps less read than he once was but you can walk into any first-year seminar and “there’s no one in the room who hasn’t read Austen”.

This points to a possible future for the humanities as a smaller, more elite discipline. The historian and podcaster Dominic Sandbrook suggests that English literature may become “the classics of the 21st century” - a subject “dominated by upper middle class, privately educated students for whom it’s a badge of prestige to know about poetry”. An alternative future for the discipline, he suggests, is “woke studies”, in which a focus on cutting-edge race and gender theory replaces old-fashioned textual analysis. The future of history is probably less woke, Sandbrook reckons, because, in history there will always be a few doughty nerds “who are interested in pikemen”.

The decline of humanities at universities is one aspect of a growing political indifference or even hostility to culture that encompasses the defunding of orchestras and choirs, the closure of libraries and falling gallery attendance. News stories are easy to overlook individually, but they add up to an existential threat to the experiences that are among the most profound available to human beings.

A country in which nobody remembers or understands art or literature or music would be a poorer and sadder place. Dame Mary Beard, who has been fighting for her embattled subject, classics, for decades says it is precisely the dreariness of that dystopian prospect that should prove motivational: “Do we want a world where no one can read Homer or understand Monteverdi? Only a very tiny minority would think that. So let’s shout about it.”