Unis urged to get serious about English proficiency

ENGLISH may become serious business as universities convince employers they are turning out graduates with communication skills.

ENGLISH may become serious business for universities as they convince the national regulator and employers that they are turning out graduates with the communication skills to do the job.

Sophie Arkoudis, from the Centre for the Study of Higher Education at the University of Melbourne, says attention will shift from a narrow focus on the English language test scores for which some overseas students enrol when they begin.

Dr Arkoudis says the focus will have to widen in order to see how students, including locals from disadvantaged or non-English backgrounds, develop communication skills as they grapple with the content of their disciplines. It will also take in how institutions measure that achievement through, for example, a final year "capstone" project.

Dr Arkoudis is the author of a new book -- the first of its kind -- tackling the vexed question of English language proficiency, according to professor of higher education Simon Marginson, who wrote the foreword.

Professor Marginson points to the sheer number of overseas students here, and two decades' of concern about the "work readiness" of overseas as well as local graduates.

"Yet, remarkable as it sounds, it has proven difficult to lodge these issues in the mainstream of teaching and learning in higher education," he says.

"The plain fact is that higher education institutions have been unable to make English language proficiency a priority.

"Rather than being treated as a core learning issue, it tends to be pathologised and marginalised.

"It becomes sidelined into low-status remedial programs provided by under-resourced specialists who are given little respect by disciplinary academics.

"So there is little co-operation between the specialist language teachers and subject teachers. There is even more variation in the integration of English language proficiency in assessment, where practices are so inconsistent as to be counterproductive and unjust."

Professor Marginson says the strength of the book is its emphasis on the development of language from the point of entry to an institution, throughout the experience of study and culminating in graduation.

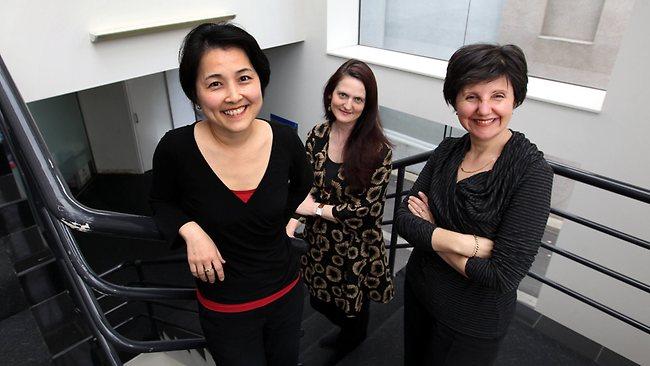

Dr Arkoudis and her co-authors -- Melbourne University's Chi Baik and Sarah Richardson from the Australian Council for Educational Research -- speak of "embedding" language in the curriculum.

Dr Baik says this need not mean a costly rewrite of content or forgoing knowledge to make room for English.

But the learning outcomes for English can be made explicit in the teaching and learning activities of a course and in its assessment guidelines. "I don't think it's a matter of hiring more language support staff but utilising them better," she says.

For example, they could work more closely with academics in each discipline to allow students to develop their English in tasks linked to the disciplinary content they have to master. "It's about making (English language proficiency) visible in the curriculum," Dr Arkoudis says.

Published by ACER, the book will be launched in Melbourne on October 4 at the Australian International Education Conference.