Not only uncertainty but also unreality. On the one hand it’s business as usual. UA delivered to the media its usual list of pre-conference good news stories, a preview of the UA chairwoman’s speech, a study showing an increase in collaboration between universities and business, and the winner of the higher education sector’s top teaching award.

But on the other hand, there’s the gathering storm, which will overshadow the conference regardless of what is on the agenda.

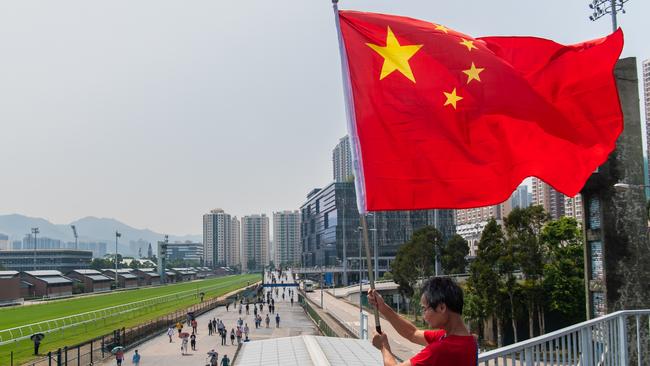

More than 90,000 Chinese university students are still caught overseas, unable to begin studies in semester one, except remotely.

That’s nearly $2bn in revenue at stake. To retain it, universities have to make sure that Chinese students stay enrolled, and that the approximately one-third of Chinese students who are beginning their course this semester don’t decide to go somewhere else.

In the best of all worlds, this will turn out fine. In a few weeks the virus will abate, Chinese students will be able to fly to Australia, and universities will manage to keep these students’ studies on track through a combination of distance learning and accelerated catch up programs.

Under this bright scenario, the more than 30,000 Chinese students who are starting courses this semester will stick with their decision to come to Australia, even if they have to cancel first semester and start in mid year. A minor advantage for universities is the fact that Australia’s July-August start to second semester is still earlier than the alternative of the northern hemisphere’s August-September beginning of the teaching year in Australia’s main competitor countries for Chinese students — Britain, Canada and the US (if Donald Trump is still letting them in).

What is the worst of all worlds? It’s the one in which the epidemic worsens and the bulk of Chinese students — those who have not managed to get here via third countries — remain in China.

Ultimately there is $6bn a year in fees that is at stake. That’s the total amount which Chinese students pay for tuition each year.

The worst world is also one in which the suspicion and mistrust of China that is growing in Australia is directed not only (rightly) at the Chinese government but also towards Chinese students.

We’ve seen enough evidence of the racial animosity that is not far below the surface of the Western world’s new class of autocrat-adoring right-wing nationalists. And we have our share of those people here. The worst of all worlds could be very ugly indeed.

What should universities do? I suggest these three things.

First, strenuously argue back against the proposition that Chinese students could be spies for their government.

The absolutely overwhelming majority are not, and should never be suspected of it. They are young people looking for an education and the experience of living for a few years in Australia.

By far the most astute thing we can do is let our Chinese guests experience the best side of a Western, market-based democracy where the media and speech is free. It will have an impact on them.

Second, never bend any principle that is fundamental to our society under pressure from the Chinese government or under the pressure of a perception of what Chinese public opinion is.

This may come at a cost, but the cost of compromising principles is worse.

Third, universities should commit to using their very best endeavours to distinguish between research partnerships with China that have military and security applications and those that don’t. There will be a difficult grey area that universities will have pick their way through. It will be tough because China is a world leader in many areas of research and its money is valuable to Australian universities. But universities need to pay far more than mere lip service to this principle to retain public confidence.

I hope in the course of the UA conference that university leaders will intensively debate their China strategy. I hope that in her National Press Club speech on Wednesday, UA chairwoman Deborah Terry will set out how the sector will tackle these issues.

Because whatever the outcome of the student travel ban in the short term, there are longer-term decisions of huge consequence to be made about the China relationship.

Never has Universities Australia, the peak body of the university sector, held its annual conference, which started in Canberra on Tuesday night, under the shadow of such uncertainty.