Stalked, spied on, assaulted: women reveal how the University of Queensland failed to take them seriously

A male student accused of stalking, watching one woman shower and sexually assaulting another was hired as a tutor by UQ.

A male student accused of stalking, watching one woman shower and sexually assaulting another while on campus was hired as a tutor by the University of Queensland two months after an internal investigation forced him to issue a written apology over one of the alleged incidents.

The male student was hired despite Brisbane Magistrates Court issuing a temporary protection order against him on behalf of one of his alleged victims. The handling of the case has been described by an anti-rape advocate as the “worst’’ she has seen by an Australian university and has left both alleged victims feeling that the university did not take their complaints seriously.

Former University of Queensland engineering student Isabel Martins, 22, and a second female student, who wishes to stay anonymous, filed separate complaints over two years against the male student.

The man is alleged to have stalked Ms Martins – including watching her shower at a university college and climbing on her balcony to watch her sleep – and to have sexually assaulted the second complainant on a university building rooftop after a date.

Ms Martins and the second complainant say their attempts to pursue complaints through UQ left them seriously shaken.

UQ vice-chancellor Deborah Terry, who was not at the university at the time of either complaint process, said she was committed to supporting alleged victims of sexual assault as she pursued sweeping changes to the university’s sexual-misconduct policies.

“I do acknowledge the complaints process can be overly complex and take too long and this was one of those times,” she said. “I am deeply sorry for the distress caused to both complainants. “Women who have the courage to come forward have to feel supported by the university.”

Ms Martins said that if the university had taken her complaint seriously, the alleged attack against the second complainant would not have occurred.

The male student has since left the university’s employment,

He said, via a legal representative, that he vehemently denied the allegations both Ms Martins and the second student had raised against him.

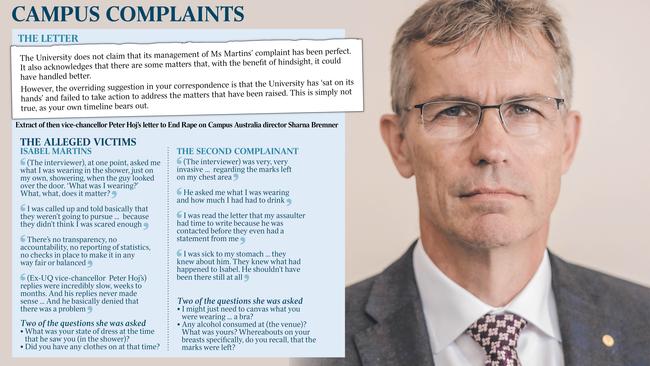

During both investigations, a UQ investigator asked the women invasive questions such as what they were wearing, what they were drinking and a series of queries about the marks left on one complainant’s breasts after she was allegedly attacked.

In a letter to an anti-campus rape activist group, the university’s then vice-chancellor, Peter Hoj, who both women have directly criticised, conceded UQ should have handled things much better.

However the letter otherwise strongly defended his administrators’ handling of the complaints.

“The University does not claim that its management of Ms Martins’ complaint has been perfect,” Professor Hoj wrote at the time.

“It also acknowledges there are some matters, with the benefit of hindsight, it could have handled better.”

How they met

Ms Martins was living at a UQ residential college, International House, in October 2017 when she met the male student and briefly dated him.

She alleged that, after she ended the relationship, the man began to barrage her with messages, acted out in public when she was around, and watched her shower several times in a shared dormitory bathroom.

Ms Martins received messages from fellow students that they had seen the male student climb on her balcony in the night while she was asleep.

After Ms Martins was initially told by UQ Security that it had no jurisdiction over any allegations at International House, despite the college being on campus, she was allowed to give a statement to the UQ Integrity and Investigations Unit.

“At one point, he asked me what I was wearing in the shower, just on my own, showering, when the guy looked over the door. ‘What was I wearing?’ What, what, does it matter?’” Ms Martins said.

Ms Martins heard little from the university on her complaint for several months.

“It was maybe four or five months; it wasn’t until the next year. When I was called up and told basically that they weren’t going to pursue — they weren’t going to do anything — because they didn’t think I was scared enough.”

Ms Martins engaged the help of End Campus Rape Australia director Sharna Bremner, a campaigner for changes to sexual assault policies at campuses nationwide. Ms Bremner appealed against the decision not to investigate to Professor Hoj.

Ms Bremner told The Weekend Australian that the handling of Ms Martins’ and the second female student’s complaints were the worst she had seen at an Australian university.

Second interrogation

More than 13 months after her first complaint was made, Ms Martins found herself being interrogated again and said she felt the final outcome was skewed towards her alleged stalker.

“Nothing had changed (in the second interview),” she said. “The interviewer kept asking me what the guy stalking me was thinking. And I kept having to tell him, ‘I don’t know what someone else was thinking’.

“The guy had to write a letter of apology to the academic registrar, not even to me. He had to stay a reasonable distance away from me, but a reasonable distance wasn’t even defined.

“The disciplinary hearing where they decided it: he was there, I wasn’t … He could say absolutely anything about me, I wouldn’t get a chance to respond. He controls the story.”

Ms Martins in December 2018 got a temporary protection order against the male student, which was followed by a five-year domestic violence order in May 2019.

But by that time Ms Martins had begun to withdraw from her studies at UQ. “I couldn’t keep up my studies, I really did try. … It felt impossible because I knew I wasn’t safe,” she said.

The second student, who has since graduated, knew the male student from high school and agreed to go for a drink for him on May 23, 2019, when she alleged he forced himself on her on the rooftop of a UQ campus building.

The second complainant was also interviewed by the UQ Integrity and Investigations Unit, and she faced questions about what she was wearing, drinking, and about the marks left after her alleged attack.

“(The interviewer) was very, very invasive about the question regarding the marks left on my chest area … there was probably like a whole five-minute part of the interview (on the marks),” she said. “He asked me what I was wearing and how much I had had to drink.”

While she got a resolution from the university quicker than Ms Martins did – with similar terms about keeping distances and halting contact – the second woman says the male student was given precedence throughout the process. “They were always contacting him first, when they shouldn’t be. He should be the last person they contact,” she said.

Two cases collide

It was only late in the UQ investigation that the second complainant found out about Ms Martins’s action against the same male student.

“That was everything I’ve worked to prevent because I knew I couldn’t stop the past from happening to me, but I felt like I could make it so it didn’t have to happen to someone else — but I couldn’t,” Ms Martins said.

The Tertiary Education Quality Standards Agency — nearly two years after Ms Bremner filed her complaint against UQ to the federal regulator — ruled that the university had fully complied with its policies in both the case of Ms Martins and the second complainant, but found “room for improvement.”

Campus reform

Professor Terry, who took over at UQ last year, is implementing changes from an eternal review of UQ’s approach to student misconduct matters late last year, which found a need to simplify the university’s policies on sexual misconduct and make it more flexible.

The vice-chancellor said on Friday that better training needed to be given to staff interviewing complainants and she was working to improve screening of potential employees.

“We have to ensure all staff through the complaints process have the right training: who’s doing the interview, where is the interview being done, what support do we need to provide to everyone going through the process,” Professor Terry said.

“And we are working towards a greater level of screening for potential employees who have had complaints levelled against them through university processes.”

Ms Martins and the second complainant have met Professor Terry and both said they believed she has good intentions, but they said the university must go further.

“The policy is terrible. Their policies aren’t enforced anyway so it doesn’t really matter,” Ms Martins said. “There’s no transparency, no accountability, no reporting of statistics, no checks in place to make it in any way fair or balanced.”

The second woman said the university “needs to pick up on their communication”.

“Deborah Terry’s doing a better job,” she said. “But there’s still a lot more that could be done.”

Ms Martins’ and the second student’s complaints are the latest in a series of sexual misconduct controversies to hit UQ in recent years.

Last year, the Queensland Supreme Court prevented the university from holding a disciplinary hearing into a medical student accused of rape. The judge partly ruled against UQ due to the structure of its policies.

Professor Hoj, who left UQ in 2020 and is now vice-chancellor at the University of Adelaide, was in charge of Queensland’s top university during the complaints process for Ms Martins and the second complainant.

The ex-UQ vice-chancellor experienced a number of controversies during his tenure including the handling of the university’s relations with China and the dismissal of a student, Drew Pavlou, who claims he was banned from campus for protesting against Beijing. The university denies Mr Pavlou’s allegations and the matter is before the courts.

Both students told The Weekend Australian that they found Professor Hoj to be dismissive compared with Professor Terry, and he took long periods to reply to their letters.

Professor Hoj on Friday would not comment directly on the cases at UQ, but said he was committed — at the University of Adelaide and throughout the university sector — to support alleged victims of sexual harassment and assault. “I express my profound regret for any victim of sexual harassment or sexual assault, and I am personally and professionally committed to helping create a better world, where our universities are safe, respectful and welcoming for all students,” he said.

“We must work hard to build the trust and confidence of our students: trust that is the necessary foundation of the systems and processes through which victims of this abhorrent behaviour can make a report and seek and obtain support.”