Only elite to survive slump in university funds

ONLY elite, research-intensive universities with global brands will exist in their current form in 15 years, a report warns.

ONLY elite, research-intensive universities with global brands will exist in their current form in 15 years, while the rest will be forced to rethink their business models as decreasing government funding, increased competition and online technologies reshape the higher education landscape.

Second-tier public universities will be forced to close, recreate themselves as niche operators or forge public-private hybrids that carve up how content and teaching is created and delivered.

The predictions are contained in a report from consultancy firm Ernst & Young, to be released today, which warns that, on current trends, universities around the world can expect significantly less government funding.

The search for new revenue streams, combined with increasing competition, sophisticated technologies, universal access to higher education and industry involvement will drive new streamlined business models unlike the large comprehensive universities of today.

"Over the next 10 to 15 years, the current public university model in Australia will prove unviable in all but a few cases," says the report, University of the Future.

"Universities should critically assess the viability of their current business model, develop a vision of what a future model might look like and develop a broad transition plan."

Lead author Justin Bokor said tension was emerging as declining government revenues combined with policies driving increases in the number of people holding a degree.

"Governments have a critical interest in the sector because we are not going to dig dirt out of the ground for the next 20 years at the same prices we've seen in the last two," Mr Bokor said.

"If we seek to become a high-performing knowledge economy, then this sector counts."

The report targets inefficiencies in traditional universities, such as more administrative than teaching staff, two-semester years leaving teaching facilities idle for 26 weeks a year, massive infrastructure costs and the requirement for teachers to be research-active.

Its release comes a week after Coalition policy-broker Andrew Robb told a seminar in Brisbane that "strangling red tape" and a "one-size-fits-all approach" to universities were preventing Australian institutions from capitalising on extraordinary demographic change in the Asia-Pacific, which would greatly increase demand for higher education.

Mr Robb and the Ernst & Young report say exploding enrolments in massive online open courses, or MOOCs, and increased demand for tertiary degrees globally point to the need for Australian institutions to broaden their scope in how and where they teach.

Mr Bokor said government were unlikely to push universities to create new business models.

"It is those universities that see the challenges, the tight financial conditions and the increasing competition that will evolve," Mr Bokor said. "Those that don't will run out of money. They will either be taken there by the market or they will fail."

At the same time, the private sector, unencumbered by cultural baggage and inefficiencies, will find ways to deliver services and "carve up the value chain".

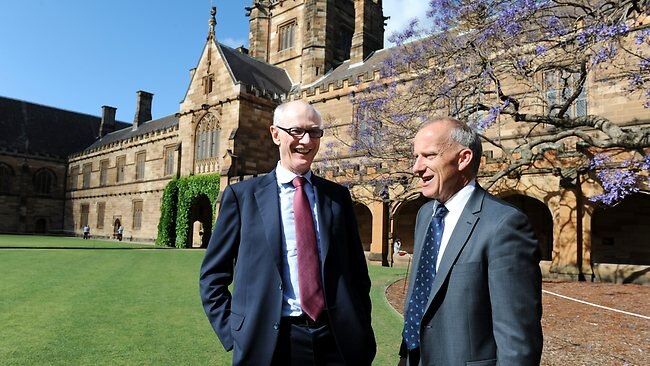

Fred Hilmer, vice-chancellor of the University of NSW, said he doubted whether universities would change as fast or as dramatically as the report implied.

"To say that school leavers (in Australia) are going to get their ATAR, get a place at university and then go upstairs and log on is not going to happen," Professor Hilmer said.

"The social side of university, especially for undergraduates, is a vital part of growing up."

The report suggests three possible future scenarios as technology, competition and funding cuts sweep the sector.

The first is a more streamlined, efficient version of the status quo.

The second, dubbed the niche dominators model, posits that, with the exception of the elite, universities will be forced to rid themselves of under-performing teaching and research areas and specialise in small target markets.

The third scenario is the transformer model in which "private providers and new entrants carve out positions in the traditional sector and also create new markets that merge with higher education".

"Google, Apple and companies in immediate technologies will find ways to create and extract value from higher education," Mr Bokor said.

"It might be distributing content or adding it. They won't necessarily play across the entire gamut, but carve out areas they can specialise in."

Mr Bokor said the successful universities would be those that saw the value in partnering with a variety of private companies that offered services in content creation, distribution and aggregation.

Belinda Robinson, chief executive of peak group Universities Australia, said the sector was more resilient than the report supposed. "Universities have been around since the ninth century and survived any number of catastrophic changes," she said.

"The challenge will be to ensure we have the policy, regulatory and funding frameworks in place to enable each and every institution to find their place of best fit in this brand new world."

Vicki Thomson, the executive director of the Australian Technology Network, which represents several "technology" universities, described the report as "a wake-up call".

"We need a sector that is more integrated into the community and by virtue of that the economy," she said.

Conor King, the executive director of the Innovative Research Universities Group, said the new report included "interesting" analysis about the changes, but he dismissed what he described as "apocalyptical" comments.