Ken Inglis: scholar focused on war memorials, ABC, Dunera Boys

Ken Inglis’s diverse and diverting scholarly contributions have helped to shape the nation’s image of itself.

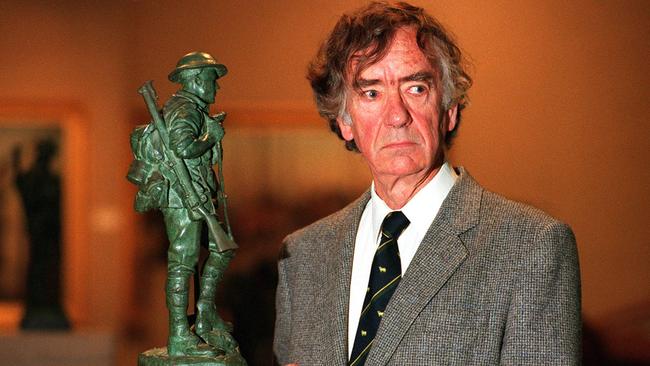

Ken Inglis, historian.

Born October 7, 1929. Died December 1, 2017, aged 88.

Ken Inglis, the great historian of Australian broadcasting, of war memorials and memorialising, and of the extraordinary Dunera Boys, died in Melbourne last week, aged 88.

He wrote of how, when the Australian Broadcasting Corporation evolved from a commission in 1983, “it was like and unlike a church, a theatrical company, a newspaper business and on a drastic view, an asylum run by the inmates”.

After a master’s degree from Melbourne University he earned a doctorate at Oxford University, returning as an Adelaide University lecturer, became professor of history at the Australian National University, and took the same role in 1967 at the University of Papua New Guinea, where he served as vice-chancellor from 1972 to 1975.

Two future PNG prime ministers were among his admirers. Mekere Morauta said: “He was such a good storyteller. We all wanted to listen to him, whatever the topic.” Rabbie Namaliu said: “He was a brilliant teacher of history, I left class yearning to learn and know more.”

His early books included histories of the Royal Melbourne Hospital and of the Rupert Max Stuart case. Fifty nine years ago this month, nine-year-old Mary Hattam was raped and murdered, her body found in a cave off a beach between the South Australian coastal towns of Thevenard and Ceduna. Stuart, a 27-year-old Arrernte man — who went on to be elected, 40 years later, as chairman of the Central Land Council — had arrived in Ceduna with a travelling funfair the night before her death, and was charged, convicted and sentenced to death.

His “confession” was allegedly made in educated English, a language he could barely speak or write. The case was thrust on to page one of Adelaide’s The News by its editor Rohan Rivett, backed by his young proprietor Rupert Murdoch, and the editor and newspaper were tried in the South Australian Supreme Court for seditious libel over a headline. The case, which attracted worldwide attention, was appealed up to the Privy Council, a royal commission was called, and Stuart’s death sentence was commuted.

Inglis wrote about the case initially for the bohemian fortnightly Nation (1958-72), and later anthologised his articles.

He wrote masterfully about the Anzacs, starting with a biography of the war historian Charles Bean, followed by The Rehearsal: Australians at War in the Sudan, 1885 and ANZAC Remembered, going on to illuminate the significance of those altars at the centre of so many villages, towns and cities in Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape.

His first history of the ABC, focusing on the years 1932 to 1983, was followed by a second volume that took the story to 2006.

Some of his key books were initially published by Melbourne University Press, with subsequent editions issued by Black Inc.

In 1952 Inglis married anthropologist Judy Betheras, with whom he had three children. She died in a car crash in 1962. Three years later, he married author Amirah Gutstadt, who died in 2015. Over the past decade, Inglis’s major project has been chronicling, with Seumas Spark and Jay Winter, the Dunera Boys. One volume has been completed and a second, for which Inglis had written four chapters, is on its way.

In 1940, Britain expelled 2036 mostly Jewish refugees on a ship, the Dunera, from Liverpool, which also carried 200 Italian and 251 German prisoners of war and several dozen Nazi sympathisers.

They arrived, after a hellish two-months journey, at Sydney, where the officer in charge was court-martialled. The refugees were sent by train to Hay, and were later reclassified by the Australian government as “friendly aliens”, half of them volunteering for military service. Many made Australia their home and became celebrated citizens.

Fellow historian Graeme Davison said of Inglis at a colloquium last year: “I could map the subjects he has written about — the history of religion, of the media, of war and memory, of nationalism and national identity, of childhood and generational change, of health and disease — and the map would show him to have been a pioneer in many of them.”

Fundamentally, Davison said, Inglis’s influence on others, and on the culture of his country, far exceeded even the sum of his diverse and vastly diverting scholarly contributions.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout