Australia-China collaborative papers made up 16.2 per cent of all Australian scientific papers last year, compared to the US (the former leader) at 15.5 per cent, the UK (11.7 per cent), Germany (5.9 per cent) and Canada (5 per cent).

It’s no surprise that China is now Australia’s lead research partner because collaborations between the two countries have been steadily increasing for a couple of decades.

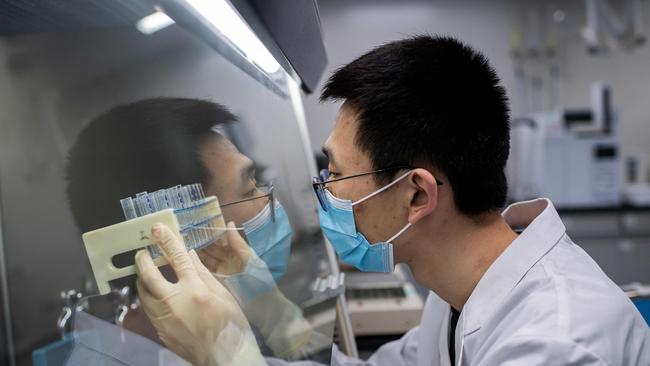

Why has this occurred? We know that China is a now a world leader in many physical sciences such as materials science, chemistry, engineering and computer science. So it’s not surprising that these are also areas in which collaboration is strongest, as researchers seek to work with others in the world at the top of their field.

The interesting thing is that the expansion of the Australia-China science relationship appears not to have been mainly funded by government research money. Australian Research Council funding for collaborative international projects in the last five years has China well down in fourth position after the US, the UK and Germany. In fact projects collaborating with the US have been funded 3.4 times more often than those with China.

So where did the rest of the money come from to pay for researchers’ collaboration with China?

Almost certainly the source of it was earnings from international students, whose numbers (particularly from China) grew at the same time as research collaboration with China exploded.

In the same period Australian universities increased their hiring of researchers from the Chinese science diaspora. Although I have no figures on this, anecdotally a large number of the Australian authors on Australia-China collaborative papers are scientists of Chinese background now working in Australian universities.

So what will become of Australia-China research links now that the income universities earn from international students has cratered? Possibly (allowing for lag effects) we have seen peak research collaboration with China.

Some will be pleased by this. Undoubtedly the China government has sought to steal IP and sensitive research with military and security applications.

But, if strict procedures are followed around research with dual military and civilian uses, this risk can be minimised, and Australia emerges a net beneficiary of research links with China.

What if the lucrative international student market never recovers? In that case the Australia-China research boom is probably over.

The number of Australia-China joint papers, as measured by Scopus, grew 13.1 per cent in 2019 which made China Australia’s largest research partner, says a new UTS report, The Australia-China Science Boom.