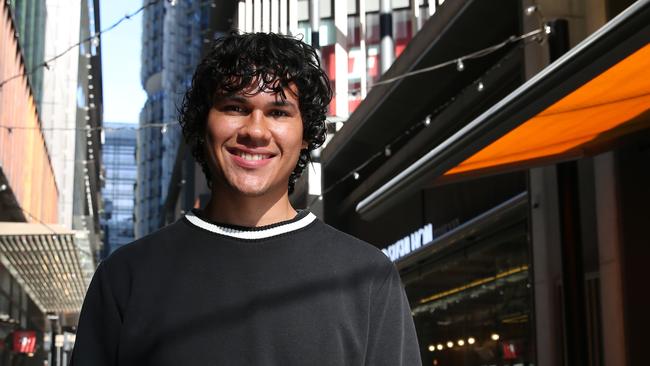

Indigenous student Injarra Harbour not the ‘average’ case

Federal government’s plan to make higher education ‘more equal’ for First Nations students.

Injarra Harbour, a university student who attended a private Brisbane boys’ school on an Indigenous education scholarship, understands he is an exceptional case.

Academically minded and with the strong support of his parents, the 20-year-old from a remote town in Queensland’s central west was always set on a path towards tertiary education, but a scholarship from the Australian Indigenous Education Foundation opened up opportunities he would never have had otherwise.

He went to boarding school 1300km away in Brisbane, where he was the second Indigenous student to captain the school, and is now interning through AIEF’s corporate partner HSBC in Sydney.

Only 18 per cent of young people in the regions have a university degree, federal Education Minister Jason Clare said last week, compared with nearly 50 per cent of people in their 20s across Australia.

According to Education Department data, 45.5 per cent of those who started a full-time bachelors degree in 2018 had graduated by the end of 2021.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders students were half as likely again to finish on time.

As part of the federal government’s Universities Accord, released on Wednesday, all First Nations students will be eligible for a funded place at university, which was previously reserved for Indigenous students from regional and remote areas.

“University funding needs greater certainty; higher education is too unequal, the Closing the Gap target for First Nations tertiary attainment needs to be narrowed and closed,” the report reads.

Harbour, a first-year law student at the Queensland University of Technology, said boosting university participation for Indigenous students was one thing but it was important to focus on getting more kids to high school in the first place.

“I don’t particularly think kids know their worth or … what they want to do, but it’s the weight of socio-economic conditions they have to live with, and barriers they face, and not being afforded the quality and time to do those things,” he said.

“I was able to form my world view with very strong people (around me), but its about increasing the average amount of people going into educational institutions.”

AIEF executive director Andrew Penfold said the scholarships were developed to remove financial barriers that may prevent Indigenous students pursuing education.

“Research has shown that when Indigenous students are well educated, there isn’t really any gap to close.”

But he said while funding for the fees is one critical success factor, it’s not the only one.

“When we are talking about young people from regional, rural and remote communities moving to large metropolitan centres where the universities are, it’s difficult to set them up for success given the acute accommodation shortages, spiralling costs of accommodation and other cost of living pressures everyone is facing.

“And if they don’t have a support network in the big cities, it’s very challenging for them to be able to focus on their studies, hence the high attrition rates we’ve been seeing.

“This is why AIEF’s university scholarships also include accommodation costs and other support, and we’ve seen this works – with AIEF retention and completion rates over 90 per cent each year.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout