Identity politics the focus of uni courses

Identity politics has become a dominating force in history courses offered by Australian universities.

Identity politics has become a dominating force in history courses offered by Australian universities, with undergraduates more likely to take classes that focus on race, gender or sexuality than the core elements of the origins of Western civilisation.

An audit of the 746 history subjects offered across 35 Australian universities this year has revealed that 244 — about one-third — focused on identity politics, meaning that history was taught from the perspective of a particular interest group, with indigenous issues, race and gender being among the most popular themes.

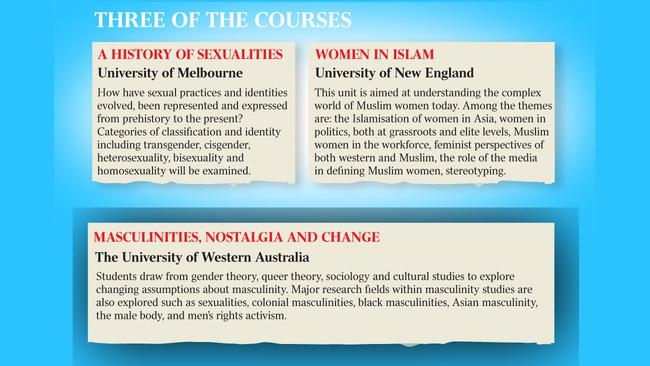

The rise of such subjects, which include “A history of sexualities”, “Masculinities, nostalgia and change” and “Politics of sex and gender” appears to be at the expense of traditional studies in Western civilisation. There were 241 subjects that could be considered core to understanding the history of Western civilisation, such as ancient civilisations, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, or the Cold War.

Only three universities — the University of Notre Dame Australia, Federation University and Campion College — offered a full suite of subjects in that area.

The audit, to be released by the Institute of Public Affairs today, is likely to inflame the long-running history wars and reignite concerns about the decline of history as an academic discipline in this country.

Author Bella d’Abrera, director of the institute’s Foundations of Western Civilisation Program, described the trend as “dangerous”, blaming academics, including historians, who have “become obsessed with what divides Australia rather than what unites us”.

Dr d’Abrera said direct consequences of the rise of identity politics included the emergence of the so-called “snowflake generation” — a term used to describe young adults quick to take offence — as well as the push to scrap January 26 Australia Day celebrations and change the name or wording on certain statues and monuments.

“The past three years in particular has seen the emergence of trigger warnings, safe spaces, male privilege workshops and rooms designated for some but not others,” she said.

“And it’s directly correlated with the rise in identity politics.”

According to the research paper, The Rise of Identity Politics — An Audit of History Teach ing in Australian Universities in 2017, identity politics is the idea that individuals are best defined by their collective identities rather than their individuality.

“It reduces the complexity of the past into this basic idea of race, gender and sexuality,” Dr d’Abrera said.

“How can we reduce the Renaissance to that? Or the industrial revolution to this idea of a male privilege that oppressed people?

“It’s a big problem that means when people finish their history degrees they don’t necessarily know what happened in the past. Or they have this idea that everything that happened was due to a struggle between the oppressor and the oppressed.”

Melbourne University’s head of historical and philosophical studies, Trevor Burnard, said universities were keen to offer subjects that were relevant and popular, and said there were elements of identity politics within some of the courses offered by the faculty, such as the history of gender and class relations, for example, in British history.

But he disputed the claim that identity politics was a dominant theme in history courses.

“We, as most Australian universities, offer a very traditional curricula, even if often taught in untraditional ways,” he said.

“Our first-year subjects … are all subjects that could have been taught to first years as subjects for the last half century without raising eyebrows.”

The University of Notre Dame’s head of history, Deborah Gare said she thought identity politics would have been more prevalent across the curriculum, given it was designed to not only teach core content and theory but also be socially relevant.

“We do need to teach the key events, themes, dates, people and outcomes — absolutely. But we also need to try to understand how and why they happened,” Professor Gare said.

“And while it’s important to know about the ‘great men’ of history, it’s also important to know about the experiences of the others around them; those outside the ruling classes; women; those of minority faiths, and that takes digging deeper.”

Dr d’Abrera said Australian society owed its prosperity and success to the developments and achievements of Western civilisation.

“Students are not being given the opportunity to learn about and understand that these are the essential features of our free society,’’ she said.

Third-year student Leah Walker, of Kwinana south of Perth, said she appreciated studying Western civilisation in her first year at Notre Dame because it gave her a solid grounding for her further studies. “Some history units might spend one week on ancient Rome, for example, whereas we studied it for 13 weeks,” the 21-year-old said. “I really enjoyed that; learning more about the world and how the past has shaped where we are today. I think it’s essential.’’