Campus concern as free speech at American universities is under threat

There is an alarming impression that a whole generation of university students has rejected free speech. That impression is wrong.

“Liberalism is white supremacy,” shouted the students, as their hapless speaker — Claire Gastanaga of the American Civil Liberties Union — looked on. The protesters at the College of William and Mary, the alma mater of Thomas Jefferson, went further. “The revolution will not uphold the constitution,” they chanted on September 27. “Nazis don’t deserve free speech.”

The ACLU’s decision to defend the free-speech rights of white nationalists in Charlottesville, Virginia, prompted the students’ ire. Because of it, Ms Gastanaga was unable to speak, and the event, Students and the First Amendment, was cancelled.

Given their well-publicised antics, it is easy to see why college students can be tarred as blinkered devotees of political correctness run amok. Students at Oberlin, a liberal-arts college in Ohio, revolted over insufficiently authentic Asian cuisine, equating it to “cultural appropriation”.

After the campus newspaper at Wesleyan University published an article critical of Black Lives Matter, students tried to defund the paper for failing to create a “safe space”. Elsewhere, students have launched campaigns against invited speakers, setting their targets on the likes of Joe Biden, Condoleezza Rice and Christine Lagarde.

Together, this gives the alarming impression that a whole generation has rejected free speech. That impression is wrong.

Illiberal impulses can be found in many corners of society, but young Americans who have attended college are more accommodating of controversial speakers, such as avowed racists, than the general population is.

Nor has tolerance of extreme views among students changed much in recent years, says the General Social Survey, which has been asking questions about attitudes to free speech for decades.

Press reports, which tend to focus on campus discord more than harmony, can create a misleadingly gloomy impression. While Charles Murray, a political scientist made radioactive by his writing on racial differences in intelligence, got into a scrape when speaking at Middlebury College, he emerged unscathed from talks at Harvard and Columbia.

The problem on campus, which is a real one, is different. A survey of 3000 college students by Gallup for the Knight Foundation and the Newseum Institute found 78 per cent favoured campuses where offensive and biased speech was permitted. A separate study found that even at Yale, a hotbed of student protest, 72 per cent opposed codes that circumscribed speech, compared with 16 per cent in favour.

Truly illiberal tendencies are limited to about 20 per cent of college students.

This is the fraction that thinks it is acceptable to use violence to prevent a “very controversial speaker” from speaking, according to a survey published by the Brookings Institution immediately after the violence in Charlottesville.

Though outnumbered, this vocal minority can have a chilling effect on what everyone else thinks they can say.

At Yale, 42 per cent of students (and 71 per cent of conservatives) say they feel uncomfortable giving their opinions on politics, race, religion and gender.

Self-censorship becomes more common as students progress through university: 61 per cent of freshmen feel comfortable gabbing about their views; the same is true of just 56 per cent of sophomores, 49 per cent of juniors and 30 per cent of seniors.

University administrators, whose job it is to promote harmony and diversity on campus, often find the easiest way to do so is to placate the intolerant fifth.

The two groups form an odd alliance. Contentious campus politics have been a constant feature of American life for more than 50 years, but during the Free Speech Movement in the 1960s, students at Berkeley demonstrated to win the right to determine who could say what.

Now the opposite is true. Student activists are demanding that administrators interfere with teaching, asking for mandatory ethnic studies classes, the hiring of non-white or gay faculty and the ability to lodge complaints against professors for biased conduct in the classroom. This hands more power to administrators.

College administrators at public universities are subject to the full demands of America’s First Amendment, which allows, among other things, hate speech and flag burning. Federal courts have struck down every speech code enacted at a public university, and the Supreme Court has declared academic freedom a “transcendent value” of “special concern to the First Amendment”.

Private universities are legally much freer to regulate the speech of students and affiliates. Many find themselves in an uncomfortable bind. University presidents want racially diverse classes of students, all of whom feel welcome. Trustees and donors, sensitive to the critique of campuses as unthinkingly liberal, want intellectual diversity. Professors want to be left alone.

As principles go, free speech can also be expensive. Security at Berkeley for Ben Shapiro, a conservative speaker, cost the university $US600,000.

Expenses to secure “Free Speech Week” at Berkeley, which was due to feature a rogues’ gallery of alt-right speakers, were expected to run to $US1 million.

The university “hoped for the best but had to plan for the worst”, said Janet Napolitano, president of the University of California system (the event was cancelled because of the incompetence of the organisers). People such as Milo Yiannopoulos, who seek out campus speaking gigs less from a burning desire to say anything meaningful than in the hope of provoking a violent reaction, have worked out a formula for needling administrators. Mr Yiannopoulos has taken to asking student groups at Harvard for an invitation, according to Conor Healy, head of the Open Campus Initiative.

Some of those standing up for free speech are trying to drain university resources while gaining personal notoriety.

Berkeley is puzzling over how to cap such spending, without penalising speakers with a particular set of views.

Many colleges are trying to pre-empt the protests. Howard Gillman, chancellor of the University of California, Irvine, gives students an annual pep talk on free speech.

Students often come to university with “no frame of reference” on free speech and the importance of academic freedom, he said.

The University of Chicago issued a firm statement, since adopted by other institutions, that says its role is not “to attempt to shield individuals from ideas and opinions they find unwelcome, disagreeable or even deeply offensive”.

A letter to the incoming class went further: “We do not support so-called ‘trigger warnings’, we do not cancel invited speakers because their topics might prove controversial, we do not condone the creation of intellectual ‘safe spaces.” There have been comparatively fewer clashes between activists and administrators at the university.

In fact, the share of schools with “severely restrictive” speech codes has declined for nine consecutive years, according to the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, a pressure group. It is now a shade under 40 per cent. The so-called Chicago principles have been adopted or endorsed by 31 other colleges and universities, including Princeton and Johns Hopkins.

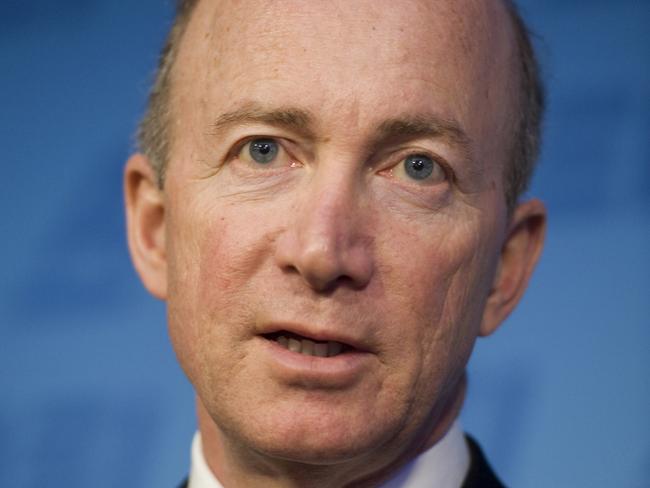

Purdue, a university in Indiana that was the first public institution to sign on to the Chicago principles, has taken a vigorous approach to teaching students about free speech under the presidency of Mitch Daniels.

Cultural-sensitivity training has been a mainstay of orientations at universities across the country, but Purdue includes sessions promoting the value of free expression. “If these other schools choose to embarrass themselves by forcing conformity of thought, allowing diverse opinions to be shouted down or disinvited, that’s their problem,” said Mr Daniels.

“If they’re raising a generation of graduates with an upside-down version of constitutional rights, that’s everybody’s problem.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout