Some of these conflicting impulses are evident in the speech which new federal Education Minister Alan Tudge will deliver on Wednesday at RMIT University in Melbourne.

The speech will be a disappointment, but not a surprise, to the international education industry. Tudge will offer mild hope of opening borders to larger numbers of students at the beginning of next year, but then list the reasons (expressed as challenges) why this may not happen.

One is that “a global authentication system for vaccination certificates” — read a vaccination passport — is a long way off. We don’t know if the government will require international students coming to Australia to be vaccinated, but it's a high likelihood.

This means we can rule out students arriving in large numbers next year because vaccinations won’t be widely available in countries such as India, and, even if they are, there will be no adequate proof of vaccination.

Tudge’s other “challenge” is that we we don’t yet know whether the vaccine prevents transmission. If it doesn’t, then even vaccinated students arriving in Australia are likely to be required to quarantine, adding yet another barrier to large numbers arriving.

Perhaps the most glaring inconsistency is Tudge’s call for more diversity in the countries that international students come from. We can read this as meaning “let’s have fewer from China”, which was the source of 37 per cent of international students in Australian universities in 2019.

Currently the impact of federal and state government policies preventing the arrival via quarantine of international students, is perverse. It increases, not reduces, the proportion of Chinese students. This is because Chinese students have shown far more willingness to study from their home country online, even commencing courses from outside of Australia in the hope of eventually coming here when borders open.

However students from elsewhere, particularly from the subcontinent, are ready to choose an alternative country — such as the US, the UK or Canada — where international students can enter.

But this is not all. There’s another baffling issue affecting international students which Tudge could help solve.

Australia has generously extended the right to a post-study work visa (allowing the holder to live and work here for a period) to students who are enrolled online and haven’t yet set foot in Australia. But these students don’t yet know if at some point the government will set a minimum time to be studying from within Australia, in order to be eligible. With border closures continuing, some of them might complete their courses before setting foot in the country.

And then there is the plight of students who, last year, followed the advice of the Department of Home Affairs and began studying online from their home country without getting a student visa (because they weren’t in Australia). But then it turned out that they needed to have a student visa to be able to count their study time toward a post-study work visa. They are being punished for innocently following Home Affairs advice.

In truth, not all the blame belongs to Tudge, or the federal government. States and territories have been slow to put forward plans for the return of students which meet Scott Morrison’s requirement for student quarantine facilities over and above what is there now for returning Australians, and which are approved by the relevant chief medical officer of the state or territory.

And this brings us to the final contradiction. Why are governments, which want to rebuild the economy, not more responsive when a $40bn export industry that supports 250,000 jobs is in danger? All our major competitor nations currently accept international student arrivals. We don’t.

Even with so much at stake, Australia can’t manage to extend its quarantine system and bring in students. Not only the policy, but soon a valuable industry and its jobs could be dust and rubble on the floor.

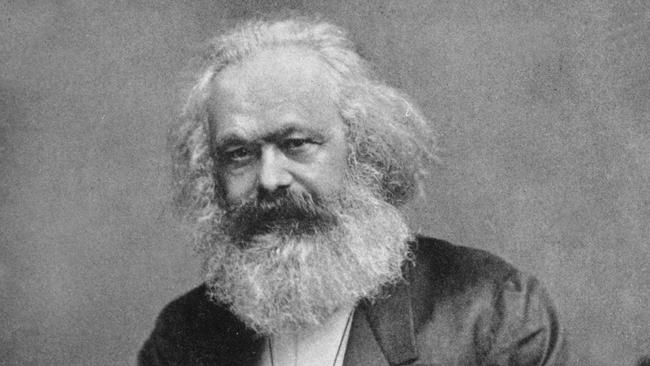

If Marx was right, and things really did collapse under the weight of their own internal contradictions, then Australia’s international student policy would be a mess of dust and rubble on the floor.