The Bible to Harry Potter: best audiobooks ever

Before the podcast, there were audiobooks and they’re still the best way to absorb some of the greats of literature.

Societies more ancient than ours knew all about the power of the spoken word as a form of entertainment and a form of enrichment. And right now we’re discovering this in a big way with audiobooks, which are having a moment. We seem to be in the process of learning all over again that it’s the power of words that keeps people sane and alive even if they’re doing it alone in Arctic wastes and ice.

Homer’s original audience knew it when they heard the Bard — blind, according to legend — sing of the wrath of Achilles, that terrible wrath which left so many heroes prey to the dogs and carrion birds.

For many years, I’ve known those fragments of the great Greek war epic (that the British poet Christopher Logue translated with spectacular licence and spectacular fidelity) in the reading of The Death of Patroclus by Vanessa Redgrave among others. Her voice, when she goes into one of Homer’s famous comparisons, is astonishing. “Remember,” she says and then pauses with what might almost be wonder, “WOLVES”. A friend said to me “She sounds like a goddess”, and there was no disputing it.

In the 1960s, at the height of his powers, Laurence Olivier did a good 10 hours or so of the greatest hits from the Old Testament with a maximum emphasis on the drama and poetry and the depth of feeling. We feel the extraordinary majesty of the Creation in that silver heldentenor voice — “in the beginning God created the heavens and the earth and the earth was without form and void and darkness was upon the face of the deep”.

There’s the crescendo of intensity at the Hebrew victory when the refugees from Egypt start their journey through the desert, the people who have been let go but then Pharaoh changes his mind and the former overlords pursue their sometime slaves only to have Moses part the Red Sea and for it then to close over the Egyptian pursuers.

“The horse and the rider he has thrown into the sea”, Larry exclaims with a great cry of triumph.

But he also captures the depth of tragedy: David is bereft as he laments Jonathan; “How are the mighty fallen … Thy love was wonderful to me”. Or his terrible words when he is a great king and hears of the death of his rebel son, Absalom. “O my son Absalom: my son, my son, Absalom. Would God, I had died for thee, O Absalom, my son, my son.”

If you want complete versions of the New Testament in the King James version you have the choice of James Earl Jones or Gregory Peck — Darth Vader or Atticus Finch.

We live in an age where a lot of people find it difficult to take the Bible or even Shakespeare out of the bookcase.

It could be said that listening to Shakespeare is preferable to watching him on a TV screen. But it’s absolutely certain that when it comes to the Bard, the listening ear beats the reading eye — the ear is much more receptive and more tolerant of elaborate forms of writing than the eye is.

When we listen to an audiobook we remember more of what’s gone before and we also anticipate the rhythm of what’s coming.

If you listen to the labyrinthine prose of Henry James or that supreme master of the complex bejewelled subordinate clause, the greatest of the French moderns, Proust, being read aloud, you will find the actor’s voice rides on the intrinsic fluency of the prose no matter how run on or complex it looks on the page.

Take, for example, Sir Ralph Richardson’s reading of The Aspen Papers, that eternal surprise of a sustained short story, and Swann’s Way, the bit of Proust that almost sounds like a straight novel, which Volker Schlöndorff filmed with Jeremy Irons as Swann and Alain Delon as the majestic old villain the Baron de Charlus.

Also, Neville Jason’s staggering solo account of the whole of A la recherche de temps perdu — Remembrance of Things Past as it was once known, In Search of Lost Time as people now say. (Side note: when the French made a comparable effort with Proust’s original –– Jason largely used Scott Moncrieff’s fabled translation –– they got a whole swag of actors from the Comedie Francaise to do the different parts of it.)

I’ve listened to Jason do the whole of War and Peace and I’ve listened to the not quite as long (but still very long) dramatisation of that Tolstoy epic with Emily Mortimer as Natasha, Simon Russell-Beale as Pierre and, Rumpole himself, Leo McKern, as the man who lured Napoleon on to his defeat, General Kutusov.

One of the odd paradoxes of the audiobook is — and this sounds weird — it can not only be more accessible to the ear (as it captures the logic of the flow) but it can also be more economical with your time than holding a book in your hands.

Why? Because you’ll be able to listen for longer and you can do it while you’re doing something else, driving to the country or chopping vegetables.

Let’s go back to Shakespeare. If you’re a Bard buff — and a lot of people are at least a bit — you would probably still imagine it too big a task to read the Complete Works every year.

In fact, it’s not if you listen to them.

With a bit of luck you could get through them in a matter of weeks. They’re longish plays but they only go for 2½ or three hours tops each.

And it makes a difference if you’re listening to the chilling spidery malevolence of Olivier’s Richard III or to the fraught soaring quality of his great contemporary John Geilgud’s Richard II as he projects that great player king who says “Let us sit upon the ground and tell sad stories about the death of kings”. And who proceeds in his own phrase to “undo” himself? Was Richard II a rough draft for Hamlet? It sounds like it if you follow it up by listening to Gielgud’s portrait of the Prince of Denmark: so rapid, so witty, so lyrical, so sad.

Maybe not as wondering and bewildered in his sadness as Paul Scofield — but then Scofield was the great King Lear of his day and there are two recordings of him in that role, one from the early 60s, with a pretty peerless class, and one from the 90s with Ken Branagh as his Fool.

The two most popular Shakespeare recordings of all time are Paul Robeson as Othello with his absolutely deep African American voice, outraged and with no shelter but the majesty of that voice, and Richard Burton’s 1964 Hamlet that has a terrific precision and eloquence: utterly tight and deadly in the comedy, indelibly memorable through all the moody mirrors of the soliloquies.

Uta Hagen, who was also the original Broadway Martha in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, played Desdemona opposite Robeson’s Othello — when they toured the American deep south in this 40s production of Othello, (which starred Jose Ferrer as Iago), they rioted when Robeson kissed his leading lady.

Shakespeare, of course, is a world and if you want to hear how that world is embodied in words and those words projected through voices, listen to what great actors can do with them.

Listen to some of the great comedies, for the light of the world. To Vanessa Redgrave, for instance, as Rosalind in As You Like It where she’s pretending to be a boy, Ganymede, who is pretending to be her, for the benefit of Orlando, (played by Australia’s Keith Michell in this recording) as she says, with an absolute skittish comic timing and musicality, “Now I will be your Rosalind in a more coming on disposition”.

Or, again, the quiet pensive sadness she brings to the role of Olivia in Twelfth Night when she falls in love with Viola, played by the great Irish actress Siobhan McKenna.

To jump ahead a few centuries in terms of literary works, McKenna with her unearthly Dublin voice is the supreme interpreter of Molly Bloom, whose extraordinary monologue concludes James Joyce’s Ulysses.

If you’ve ever been baffled at that unpunctuated prose, just listen to the way McKenna rides through its utterly exotic mixture of musing, randiness and lyrical surge. This is probably the supreme act of interpretation Joyce’s book about the wanderings of his latter day Odyseus, Leopold Bloom, has provoked. McKenna is also marvellous to listen to in George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan and she is dazzling when she recites the poetry of that greatest of Irish poets, William Butler Yeats with Micheál MacLiammóir the Irish theatre manager.

MacLiammóir did a virtuoso one-man show about Oscar Wilde, The Importance of Being Oscar, while the reading of the Christmas dinner scene, from A Portrait of The Artist of A Young Ma n by Cyric Cusack, (another of the Irish greats), will never be equalled.

Audio brings us every kind of writing, not just great art.

You can get all sorts of recordings of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes including Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce recapitulating their Holmes/Watson act that dates back to the 40s films. Was Conan Doyle essentially a trashmeister but an unforgettable one, with his smoke-laden London and its hansom cabs and genius solutions from the most legendary detective of them all? Regardless, long ago radio brought together not only Sir John Gielgud and Sir Ralph Richardson as the super sleuth and his Boswell respectively, but also none other than Orson Welles as the evil Doctor Moriarty in the creme de la creme of Sherlock Holmes recordings.

And, of course, every variety of fiction and non-fiction is now available in audio form and sometimes there are delicious crossovers.

My Apple Music recording of a splendid abridged version of Antony and Cleopatra with Peter Finch as the Roman hero who became a bit crotch-struck, and Vivien Leigh as the dazzling queen of Egypt, directs me to the Beatrix Potter Peter Rabbit stories, also read by the former Lady Olivier (who incidentally ditched Sir Laurence for Finch).

Best audiobooks for children

Leigh, who defined the roles of Scarlett O’Hara and Blanche Dubois on screen, when narrating the most cutsey pie of stories for young children, brings to them the same majesty as she does to the so-called Serpent of Old Nile, which is the greatest role for an actress in the repertoire.

If you were compiling a list of recordings for kids you might do worse than start with the shortish recording they used to play on the radio in my childhood of The Happy Prince by Oscar Wilde with Welles as the narrator and voice of God and Bing Crosby as the statue of the Prince. Crosby had as beautiful a speaking voice as he had a singing one. “Swallow, swallow”, he would croon like an angel. “Will you not stay with me one night longer?”

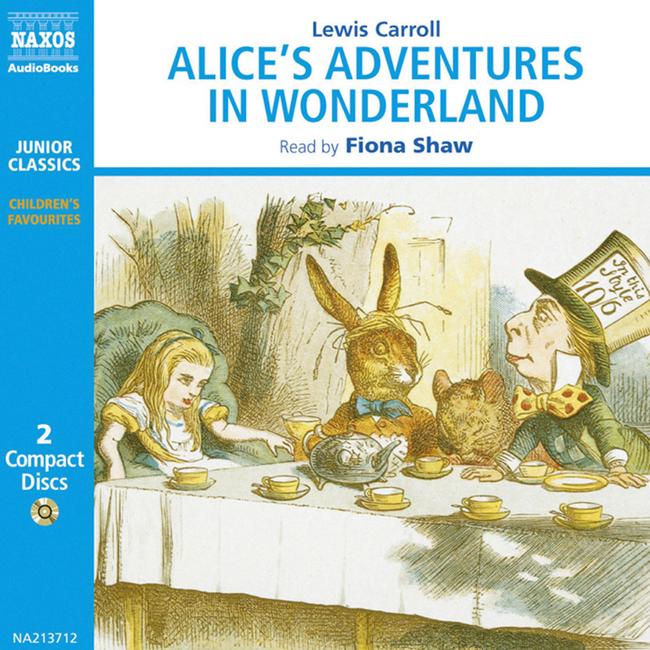

If you wanted great children’s books to flame into life at the sound of a beautiful voice you might want to invest in Fiona Shaw (from Killing Eve) reading Alice In Wonderland or you might like an older dramatised version such as the Jane Asher one from the early 60s. (Fun fact: she used to be the girlfriend of Paul McCartney.)

Stephen Fry, who’s done his own version of Wilde’s fairytales with Vanessa Redgrave, will never be bettered reading Harry Potter though it was one of the sorrows of his life that he didn’t give Professor McGonagall a Maggie Smith-style Scottish accent. Fry is dazzling though and you could argue that he gives the JK Rowling books their ideal reading.

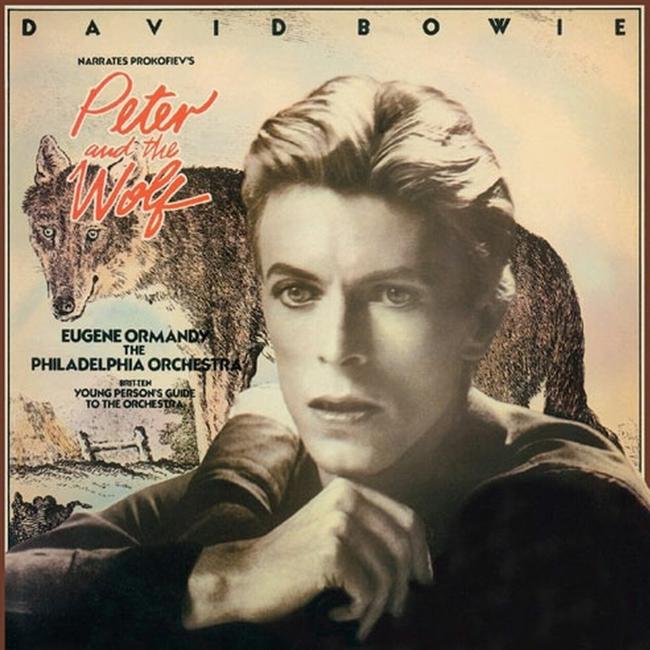

Somewhere along the line you would want one of the versions of Peter and the Wolf. A generation who grew up on Star Wars might want Obi-Wan himself, Sir Alec Guinness, doing the honours and if you’re a Star Trekker there’s Patrick Stewart. But isn’t there something irresistible about a master of music, and the histrionics of music, David Bowie introducing the parts of the orchestra and their interactions to the ankle-biters.

Every child deserves to be introduced to the Just So stories of Kipling and here Jim Weiss is the go-to person. Kipling, of course, is a writer with a supreme grasp of the populaire. When I listened to Anthony Quayle (a great Falstaff to Burton’s Prince Hal, notable as Anthony to Pamela Browne’s Cleopatra in a famous recording, perhaps the very best audio Macbeth) reading Rikki-Tikki-Tavi I was transfixed as I had been decades earlier when my headmaster — who was slumming it — took a class of 11-year-olds by reading that ravishing story of the mongoose.

Kim, that extraordinary homage to the wilderness of splendours that is cultural and religious India is great in any version (as Edward Said, the critic who rejected Orientalism had to admit) and I remember a fine abridged one by Tim Pigott-Smith. This is one of the greatest children’s books ever written and it has a depth and poignancy because it is a book for children that uncovers the innocence of childhood — in the face of the great mysteries — as well as the sense of adventure. I think the under 10s could cotton onto it despite its wisdom. There’s a complete version by Sam Dastor.

Of course there is the enchantment of Peter Pan and you can get an all-star version with Kit Harington from Game of Thrones, David Walliams and Helen McCrory.

The Wind In The Willows is a book that leaves a lasting impression of the enchantment of childhood and there are all kinds of versions of it, including one by Sir Michael Hordern, one by June Whitfield and an early 60s dramatisation with Shakespeareans such as Patrick Wymark and Frank Duncan.

A.A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh books have been narrated for kids by Judi Dench together with Stephen Fry, Geoffrey Palmer and Michael Williams.

The standard serviceable version of all the parts of the Lord of the Rings is by Rob Inglis but the standout here is in fact the BBC dramatisation from the early 80s –– which Peter Jackson paid homage to when he cast Ian Holm as Bilbo Baggins. It has a very dynamic Aragon from Robert Stephens, Holm is a superb Frodo, and Sir Michael Hordern a lordly but also philosophical Gandalf. Given the care that went into the films, it’s extraordinary how much this radio version equals and arguably outshines them.

Nor should we forget Tolkien’s Oxford confrere and comrade in religious commitments CS Lewis even though they didn’t like each other’s books. The old abridged version of the Narnia chronicles are wonderful because they streamline the books so adeptly: Ian Richardson and Claire Bloom are especially fine. But there are also complete versions by the likes of Michael York, Lynn Redgrave and Derek Jacobi that are about as good as you could wish for.

But audio will provide everything you could possibly want in the way of enthralling entertainment for children. I see no reason why a 10-year old couldn’t listen to Sissy Spacek’s enthralling rendition of To Kill A Mockingbird and, although Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials wouldn’t be suitable for anyone under 13 or so because of the blackness of its vision, you can certainly get a superb multicast version of the whole long sequence.

I also listened to the latest volume of The Book of Dust read superbly by Michael Sheen. And it’s also worth remembering that children can cotton on to one of the greatest writers in the English language, Charles Dickens. There are marvellous versions of the various novels by Martin Jarvis who channels Dame Edith Evans as Aunt Betsy Trotwood in his David Copperfield.

That adoptive Australian the great Miriam Margolyes does the piping voice of Oliver and the high lilting voice of Fagin to the manor born in her marvellous unabridged Oliver Twist.

I listened to every word of her immense, towering version of Bleak House and I knew, listening to Margolyes, that Lady Dedlock was a woman who knew her own physical beauty, that Joe knew the sadness and limitation of all things, that there were lawyers who cared for nothing but the brutality of their own interests like Mr Tulkinghorn.

Children should listen to masterpieces such as Huckleberry Finn and they should listen to the extraordinary tales of Dickens, who is the greatest master of dialogue in the language.

We are going through a golden age with the audiobook at the moment — partly, one suspects, because people are ceasing to be able to read literary, and especially classic fiction, in the same way that they once ceased to have the habit of understanding musical scores.

But just as we can, with the right amount of effort, still enjoy classical music, so the richness of the world’s literature, ancient and modern, can flood to us as the sound of glorious stories.

You can choose your poison. You can listen to one of the new razor-sharp psychologically adept Karin Fossom crime stories. You can listen to le Carré, you can listen to Trent Dalton’s Boy Swallows Universe as well as so much that’s coming out right now.

If you’re going to travel any distance in the future or stay in the kitchen chopping vegetables, bear in mind that audiobooks will keep you going at least as well as any podcast.

-

For your listening pleasure

For vinyl aficionados, some of the older titles in this list are available on eBay. Buy from bookstores, download from Audibleor stream via Apple music or Spotify

● Laurence Olivier in a Dramatic Performance of The Bible, GMT Productions, 1974

● Othello, William Shakespeare, starring Paul Robeson and Uta Hagen, Columbia, 1953

● Richard Burton’s Hamlet, Onward Production and Paul Brownstein Productions, 1995

● Ulysses: Soliloquies of Molly and Leopold Bloom, Cademon, 1965

● A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce, narrated by Cyril Cusack,

1959

● The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle, starring John Gielgud, Ralph Richardson, Orson Welles, 1954

● Antony and Cleopatra, William Shakespeare, starring Vivien Leigh and Peter Finch, 1964

● Peter Rabbit, Beatrix Potter, read by Vivien Leigh, HMV, 1963

● Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll, read by Fiona Shaw, Naxos, 2000

● Harry Potter books, JK Rowling, read by Stephen Fry, Bloomsbury Children’s Books, 1999-2007

● David Bowie Narrates Prokofiev’s Peter and The Wolf, RCA, 1978

● Just So Stories, Rudyard Kipling, read by Jim Weiss, Listening Library, 2011

● Peter Pan, JM Barrie, read by Kit Harington, Penguin Audio, 2020

● The Wind in the Willows, Kenneth Grahame, narrated by Michael Hordern, 1983

● Lord of the Rings, BBC radio plays, adapted by Brian Sibley, 1981

● To Kill a Mockingbird: 50th Anniversary Edition, Harper Lee, read by Sissy Spacek, Random House Audiobooks, 2010

● The Book of Dust Volume One and Two, Philip Pullman, narrated by Michael Sheen, Penguin Random House Audio, 2017, 2019

● Boy Swallows Universe, Trent Dalton, narrated by Stig Wemyss, HarperAudio, 2018

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout