David Attenborough recalls A life on the Planet in first feature film

It was in Sierra Leone in the 1950s that the on-air talent for a show called Zoo Quest suddenly fell ill ... and David Attenborough’s life changed forever.

At 94, David Attenborough is “still learning”, he says, still reflecting, still making discoveries. His new film, A Life On Our Planet, is a summation of accumulated wonder and curiosity. It’s also what he calls his “witness statement”, an account that covers some 70 years of exploring the natural world and bringing it to our screens.

This time, more than ever, wonder is accompanied by a warning. For decades, Attenborough has been a chronicler of wilderness, of remote places, of the secret lives of flora and fauna in every part of the natural world. In recent years, he has begun to alert us in no uncertain terms to the dangers this world faces.

In A Life On Our Planet, Attenborough takes us through his own life on Earth, from his boyhood fascination with fossils, searching for “buried treasure” in quarries, to his first TV broadcast, and through series after series that took him from Serengeti to Antarctica to the depths of the ocean.

That accumulation of experience — and of the footage that records it — is a kind of testimony in itself. But he hadn’t thought about it in those terms initially.

“I can’t pretend that it figured largely in my mind. It wasn’t until filmmaker friends put it to me,” he says. “And I suddenly realised that, at the age of 94, I have been a witness to what’s been going on, not simply because of my age, but also because I’ve been wandering about so much.

“Looking back at it now, I see the pattern, I see the shape, I see the way the world is going, I suppose.” This film is a testimony to the beauty, resilience and delicate balance of nature, and to the destructive impact of human behaviour on it, in the space of an astonishingly short time. As Attenborough says at the beginning: “It’s happened in my lifetime. I’ve seen it with my own eyes. This is my witness statement and my vision for the future. The story of how we came to make this our greatest mistake and how, if we act now, we can yet put it right.”

A Life On Our Planet begins not in a rainforest or on a savannah or an ice floe, but with Attenborough standing in the ruins of the abandoned city of Chernobyl. Here, in April 1986, 50,000 inhabitants were evacuated in 48 hours when an explosion at a nearby nuclear power plant led to an environmental catastrophe.

“I’ve forgotten whose idea it was,” Attenborough says of this stark location choice. “It wasn’t mine. But I saw very well what a vivid and powerful opening it would make.” He stands in a broken place, a world of abandoned houses, deserted schoolrooms, of peeling walls, broken glass and rubble, with traces of a human presence, such as books scattered on a classroom floor.

What happened in Chernobyl, according to Attenborough, was a disaster caused by a combination of “bad planning and human error”, but it was “a single event”. What he wants to draw attention to, he tells us, is something similarly catastrophic but harder to present: a tragedy “still unfolding, and barely noticeable day to day … the loss of our planet’s wild places. Its biodiversity”. It’s an introduction to another narrative of human error on a devastating scale.

This isn’t really the kind of story he thought he would be telling when he started his career. His life as a broadcaster began straightforwardly enough in the 1950s, when he joined the BBC after studying natural sciences at Cambridge. “I went into it simply because I wanted to make films about the natural world,” he says. “I didn’t go into it as an action man.” If by action he means activism, then that was true at first. But he was certainly active.

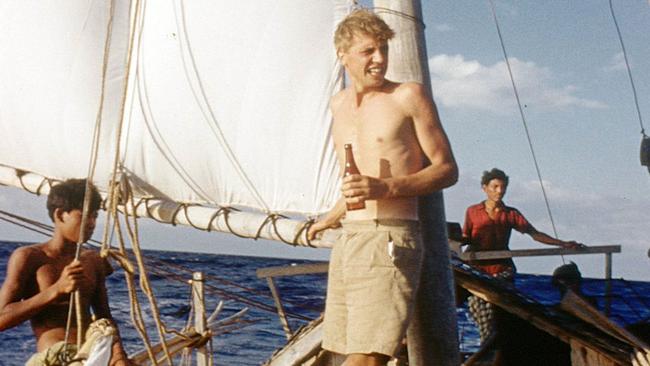

In those early shows, all youthful enthusiasm and khaki shirt and shorts, he might have looked like Tintin the naturalist.

He had started out as a producer; got his break as a presenter by accident, in Sierra Leone, when the on-camera talent for a show called Zoo Quest fell ill. The program travelled to, among other places, Madagascar, Papua New Guinea and northern Australia. In the mid-1960s, he took a job as network controller of BBC 2. By 1973 — when he was in consideration for the job as director-general of the BBC — he was keen to return to making programs full-time. And in 1979, with the blockbuster series Life On Earth, he set a new benchmark for natural history television.

He has hardly stopped since. He has become a beloved figure, almost an institution, but that air of youthful enthusiasm has never quite left him. Recognition of his contribution takes many forms: more than a dozen species are namedafter him, including a snail genus found only in Tasmania, Attenborougharion rubicundus. He’s frank about the post-war period in which he got his start, calling it “the best time of my life. The best time of our lives”; an era of prosperity and growth in much of the world that also sowed the seeds of global overconsumption and reckless destruction.

Gradually, Attenborough says, he realised there were other stories that needed to be told, other implications to what he was filming, even as he celebrated the wonders of the natural world in pioneering fashion. “There was a sense of responsibility that you got after a bit. You realised that you couldn’t just be there to be enjoying yourself. If you had the luck to be given these insights, you had the responsibility to do something about it. And that need is greater now than it has ever been.”

A lightbulb moment, he says, came in 1998, during the making of The Blue Planet, when he saw bleached coral reefs for the first time. There’s footage of this: in his voiceover, Attenborough describes the sight with a kind of awe: it seems beautiful at first, he says, then “suddenly you realise that it’s tragic, because what you’re looking at is skeletons, skeletons of dead creatures”.

Recalling it now, he says: “I couldn’t really believe it, the first time I saw a bleached reef.

You thought it was just an accident or a freak or something. The notion that it was a warning signal of what is likely to happen to the world’s reefs was a horrible realisation.

“Scientists started to discover that in many cases where bleaching occurred, the ocean was warming. For some time, climate scientists had warned that the planet would get warmer as we burned fossil fuels and released carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. A marked change in atmospheric carbon has always been incompatible with a stable Earth.”

Right now, he says, COVID-19 could well be included in the catalogue of errors he compiles in A Life On Our Planet. “The question is whether these kind of epidemics find their root in, or have some relevance to, what we have been doing to the natural world.”

Destroying the balance of nature, he suggests, can be said to contribute to epidemics past and present.

He says in the film that he is almost entirely vegetarian. “If we all have a largely plant-based diet, we would need only half the land we use at the moment. And … could increase the yield of this land substantially.” In his own case, he says: “My attitude has been changing. Thinking about these problems, I suddenly find without taking any great dramatic resolution, I’m eating hardly any meat at all.”

A Life On Our Planet is not simply about the natural world under threat: it’s also a blueprint for the future, an argument for a sustainable way of life in which renewable energy sources replace fossil fuels, reforestation is possible, and human demands on the natural world can become less consuming and destructive.

At the end, returning to the opening images of Chernobyl, we see renewal there too: the natural world is taking back the space in unexpected, moving ways. Although Attenborough paints an often bleak picture, he has enough optimism to believe change can happen, balance restored. “If you look at kids, at young people today, you don’t see doom and gloom, you see you see action, you see determination, you see optimism.”

He does admit a certain angst at times. “You despair when people in power or people who are put in power refuse to accept that two and two is four.” What he hopes for from politicians is that “we can encourage them to believe that we, as citizens of the world, as well as citizens of particular countries, recognise there is a world problem. And if we’re going to solve the world problem, it’s going to [involve] giving and taking, sorting out who’s going to tackle what and how”.

And he prefers action to angst. “I don’t spend time trying to work out what the cash balance is, as it were, between optimism and pessimism. You can’t afford to simply throw up your hands and say, ‘well, I don’t care’. You have to do your best. You can see what the possibilities are. You can see that the solutions are there.

“I was going to say, ‘that’s the terrible thing’. But what I mean is that we know what has to be done. What we now have to do is to form a new kind of internationalism, in which we recognise there’s giving and taking between nations as to the responsibilities and the rewards that each of us has [in relation] to every ecosystem.”

The dream of “rewilding the planet” and creating a sustainable future is feasible; he is sure of it. As we talk of “rewilding” he says, almost wistfully: “You and I are speaking not only at opposite ends of the world, but opposite ends of the issue you’ve just raised. I mean, [in Australia] you’ve got enormous quantities of real, genuine, dyed-in-the-wool wild. Here in Britain, I don’t think you can really find anywhere that’s actually wild, except perhaps the top of the Cairngorms … All other parts of this blessed land in which I sit are now dominated by homo sapiens.”

David Attenborough: A Life On Our Planet screens for a limited season at selected cinemas (except Victoria) from September 28, accompanied by a specially recorded Q & A with Attenborough and Michael Palin. For details au.attenborough.film. It will screen on Netflix in Australia later this spring

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout