What is ‘The Beast’? Understanding motor neurone disease

Neale Daniher, the newly named Australian of the Year, has battled MND since 2013. His fight to raise awareness and support research into this debilitating condition continues through his charity, FightMND, bringing crucial attention to a disease that still eludes a cure.

Our newest Australian of the Year, Neale Daniher, was diagnosed with motorneurone disease – MND – in 2013 and his condition was made public the following year.

Daniher calls his condition ‘the beast,’ and rightly so. MND is a rare but relentless set of diseases that cause progressive disability and often death.

With the surge in public interest that comes from this award, many Australians will now have heard of MND but not understand this complex medical condition. Indeed, many doctors find understanding MND complicated and treating it can be ferociously difficult.

Neale Daniher understood the urgent need for better understanding and treatment of his condition when he co-founded his charity FightMND.

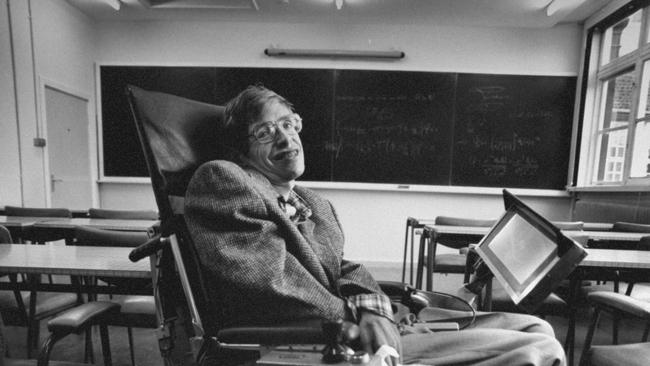

MND is not a single disease, but a large number of related conditions all of which affect the function of the nerve cells in our bodies that control movements. About 1500 Australians are affected at any one time. World-leading scientist Stephen Hawking and American baseballer Lou Gehrig died from MND. Indeed, MND is sometimes called Lou Gehrig’s disease.

Motor neurons are the nerve cells that send instructions out to the muscles and other structures in our bodies. The main bodies of these cells are located in our brains, and deep within our central nervous system and spinal cord. They send delicate nerve tendrils to the most distant parts of our bodies and are the longest cells of all, often measuring metres in length.

When MND strikes, these nerve cells degenerate and die. Unfortunately, our bodies have no plan B: there is no other way that messages can get from our brains to our bodies. For this reason, MND has a severe and permanent effect on movement and other bodily functions. If the muscles involved control breathing, speech, or swallowing, people with MND can have severe problems and become very vulnerable.

The clinical course of MND varies in individuals. Some types of MND affect babies and small children and can progress rapidly and lead to death. These diseases commonly have a genetic basis and are inherited from parents. Other forms progress slowly over time. On average, though, the commonest forms of adult-onset MND will progress irreversibly and cause death over about three years.

The symptoms of MND reflect the damage to the motor neurons that control muscles. Muscle weakness is the hallmark of MND and this can affect all movements of the body. When the muscles that control our breathing are affected, it causes breathlessness, low energy, and proneness to chest infections that can be extremely serious.

The first signs of MND can be subtle and difficult to interpret, even for experienced specialists. For this reason, there is commonly a delay between the onset of MND and its diagnosis. To make things worse, there is no specific test for MND. Making the diagnosis can be challenging and involves investigation of muscle function and tests such as MRI to rule out other conditions such as multiple sclerosis or tumours.

The treatment of people suffering from MND is complex and involves a team of experts such as neurologists, physiotherapists, occupational and speech therapists, and other experts. Symptoms such as the inability to move, chew, speak or swallow all have a severe effect on sufferers’ mental health, and so psychologists and social workers are commonly part of the team.

Progress in our understanding of MND has been frustratingly slow because the brain is difficult to study. Funds raised by Neale Daniher’s FightMND charity have gone to research aiming to uncover the ultimate causes of MND and, with this knowledge, to fight it. There is an enormous amount we still do not know about MND.

Fortunately, progress is being made. A number of new drugs are available that slow or improve some of the symptoms of MND. Others are under trial and development. Unfortunately, there is no cure as yet, and at best these drugs slow progress of the disease and may improve the lives of people affected. These are important outcomes and should not be discounted.

Research is uncovering many genes that seem to be associated with MND, and this is very promising work. By understanding which genes are malfunctioning, scientists can improve their knowledge of the underlying disease process in the motor neurons and – potentially – change the progress of this nerve destruction for the better.

MND is a feared disease and deserves its description as ‘the beast.’ The incredible fundraising of Neale Daniher’s FightMND charity is supporting researchers to understand better this relentless disease. Daniher’s recognition as Australian of the Year will doubtless lead to a surge in public interest in the deadly enigma of MND.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout