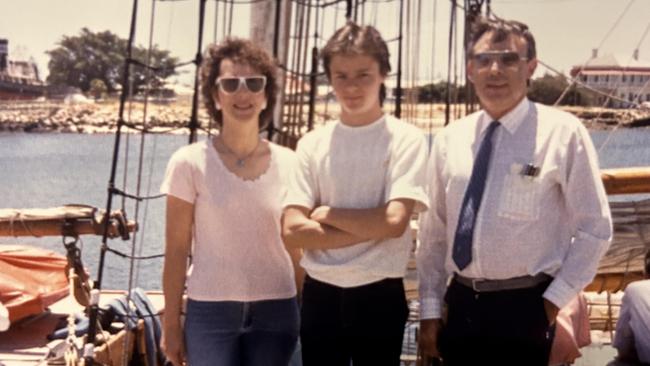

Watching my dad’s death by a million missing memories | Anthony Keane

It’s a heartbreaking reality affecting tens of thousands of Aussies every day. In this raw and personal account, Anthony Keane tells what it’s like losing a parent to Alzheimer’s.

It’s the eyes that hit me the hardest.

Sometimes they bulge scarily as he stares straight ahead and chants incoherent words, while his hand grabs rhythmically at his bedsheet or a teddy bear the nursing home carers have provided.

Other times his eyes have a look of sad resignation of his situation, and a tear rolls down his cheek as he sighs heavily, clearly frustrated that his disintegrating brain will not let him communicate normally with his loved ones.

Just one year ago, my father was walking, talking and living a relatively normal – although increasingly confused – life as his Alzheimer’s disease progressed following a diagnosis in 2021.

Now his brain has robbed him of the ability to sit, stand, feed himself and do all the daily things most of us take for granted, and we are in a twilight zone, a long goodbye, and a cruel waiting game until this horrible disease takes him completely.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia,and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare estimates that more than 411,000 people were living with dementia in 2023.

This is forecast to more than double within 35 years to about 850,000, and the AIHW says almost two-thirds of dementia patients are women.

Multiply those numbers by countless family, friends and carers, and it’s clear that dementia’s tentacles are spread across all corners of Australia, and getting stronger.

The huge numbers of current and future sufferers offer some solace to victims and their families that they are far from alone with their experiences, not that it makes anyone feel better about dementia diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s.

My father’s rapid deterioration since the middle of last year was shocking at first, but seems to have plateaued in the past few months – albeit at a level that has him almost completely bedridden in a palliative care room at a nursing home.

When visiting, I sit on the floor on a mat next to his bed that has been lowered to ground level to prevent a dangerous fall, while Neil Diamond, Rod Stewart, Simon and Garfunkel or a bit of Barnesy play on a bright red radio on the window ledge.

I’m shocked by the sight of his now twiglike arms and I rub his head silently hoping that it will deliver a miracle recovery by stimulating his shrinking brain. It won’t. He forgot my name eight or nine months ago, although his eyes still have flickers of recognition when he sees me.

Dad still reacts with smiles and a few words of gobbledygook when the nurses and carers enter his room to assist him, and he often speaks meaningless sentences without prompting – often related to his work many decades ago.

However, ask him a direct question and his brain refuses to co-operate, sometimes spitting out unusual sounds or chants or just complete silence.

Dementia runs in my family. Dad’s mum – my Nanna – had it when she died aged 99 but she lasted almost a quarter of a century more than her son is today. My grandfather on my mum’s side died with dementia at a relatively young age.

This family history has prompted me to do plenty of my own research – some tell me obsessively – about ways to beat or at least delay dementia’s symptoms if I too am destined to suffer from it.

Modern medicine has helped human bodies last longer but not yet our brains, although the latest studies suggest the simplest things may help prevent it.

Exercise. Education. Social interactions and sleeping at least seven hours nightly.

All these have become much more important to me as I have watched my father’s swift decline.

Dementia Australia has a long list of ways to reduce your risk of dementia. These include:

• Avoid excessive alcohol consumption – no more than 10 standard drinks a week and less than four on any given day.

• Don’t take drugs – they mess with the minds of everyone and can cause permanent changes in the brain, none of them good.

• Work on good heart health, as cardiovascular issues such as high blood pressure and high cholesterol are linked to a higher risk of developing dementia later in life. Heart health can be improved by exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, getting regular medical

check-ups, limiting alcohol and avoiding tobacco.

• Give yourself mental exercises to help build brain health and strengthen the connections inside it. This can include reading, cooking, painting, puzzles, musical instruments, learning a language or taking a course.

• Take care of your hearing and vision, because people with hearing loss are up to five times more likely to develop dementia, while there are also dementia links to vision impairment.

• Stay social, because loneliness and depression are linked to higher risks of cognitive decline.

• Catch up with family and friends or join social groups, sports clubs or other group activities.

• Have good nutrition and protect your head from heavy knocks.

• Try to sleep for seven or eight hours a night, as it is important for brain health.

• Keep exercising. People who are physically active during their lives, and especially after age 65, are less likely to develop dementia.

Even if these lifestyle changes do not prevent Alzheimer’s, they will help ward off a lot of other lifestyle-related illnesses and diseases as we age.

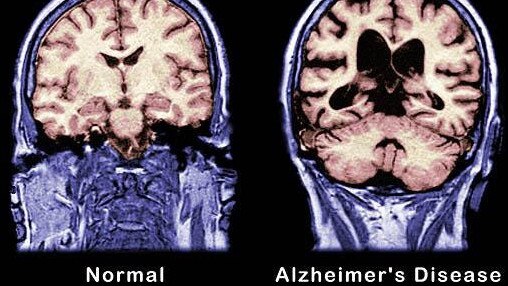

Alzheimer’s disease was first reported in 1906 by German psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer, who noticed brain tissue changes in a woman who died with a strange mental illness marked by memory loss, unusual behaviour and language problems.

In her brain were abnormal plaques and tangles of fibres, which are still considered key features of the disease that interfere with the transmission of messages.

As Alzheimer’s disease progresses, healthy neurons lose their connections and die; images you can find online showing scans of a healthy brain compared with a shrunken, shrivelled Alzheimer’s patient’s brain are shocking.

More and more Australians are set to suffer dementia diseases such as Alzheimer’s as our population ages rapidly.

Dementia Australia says an estimated 34,200 South Australians have dementia and this is projected to climb to 55,600 by 2054.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics has forecast that between 2022 and 2071, the proportion of people aged over 65 will climb from 17 per cent to up to 27 per cent.

In the same time frame Australians aged over 85 will potentially triple, from 2.1 per cent to up to 6.4 per cent.

Alois Alzheimer never reached old age himself. He died aged 51, of heart failure following complications from a severe cold.

Today, genetic testing is available to help people discover whether they are 8-10 times more likely than the overall population to get Alzheimer’s disease.

Actor Chris Hemsworth discovered he was in this group when filming a documentary series about longevity in 2022.

I’m currently wrestling with whether I should take the same genetic test, and have spoken with my doctor about this.

Some doctors say people who find out their brain may be a ticking time bomb can be badly impacted mentally.

However, I’m already operating on the assumption that I have those dodgy genes, given the history of Alzheimer’s on both sides of my family, so anything other than that would be a bonus.

I also operate on the assumption that I could get hit by a bus tomorrow, so worrying about what I may or may not experience 20 or 30 years from now is not worth it.

Dementia already is the second-biggest cause of death in Australia, and the leading cause of death among women.

It’s slightly comforting to know that its sufferers are part of a large group, but that doesn’t erase the stigma dementia still carries.

Many families and friends refuse to visit dementia patients, preferring to remember their loved ones when they had healthy brains, or they are too scared to sit helplessly next to someone as their mind disintegrates over many months or years.

There’s no voluntary assisted dying for dementia sufferers, because once they are diagnosed they are viewed as not mentally fit enough to make decisions about ending their life. I worry that when Dad’s brain finally takes away his ability to eat or drink anything, he will starve to death, but medical professionals say that is unlikely and by that stage dementia patients do not realise or feel it.

So it’s a long, sad and painful goodbye, and I often feel ashamed when I whisper to Dad that he should feel free to leave this world if he wants to escape his horrible deterioration and the increasing indignities this previously proud and strong man has suffered in recent months.

I don’t know if he understands me. And I never will. ■