Thoughts on Elle Macpherson, cancer, death… and the Salt Nightclub murder trial

This is my story of surviving cancer (so far), and why I believe stress may play a role in this cruel, brutal and insidious disease.

This story is about cancer, prostate cancer and surviving 20 years later.

In November 2004, a close friend’s father died. Not from cancer, as far as I know. He was a great lawyer and worked into his 80s at a large Melbourne firm supporting and mentoring the new generation.

On the way to his memorial at his house, my mobile rang and my clerk asked me if I would accept a brief to prosecute seven young Vietnamese boys for murder. Three of them were facing three counts of murder. It was the Salt Nightclub trial. The trial judge would be my informal mentor, Justice Robert Redlich. My junior would be a close friend and my clerk also told me that I knew a number of the defence barristers.

I had been a silk for three years and this was the type of case that silks are expected to run. Without hesitation I accepted the brief. Looking back now, it seems fitting that I accepted what could have been a death sentence at a funeral for a lawyer.

I spent the balance of 2004 and the summer break preparing for the trial and working with the team of police and lawyers, as well as the families of the victims of the murders.

On a deep winter Sunday night in Melbourne, a large group of young men, many from Vietnamese families, attended the Salt Nightclub in South Yarra. For reasons that weren’t entirely clear a fight broke out and a group of boys chased another group along Chapel Street towards the Yarra river. Some also followed in cars. At the intersection of Chapel Street and Alexander Avenue, one of the victims was chopped to death with samurai swords. Two other victims, terrified by what they saw, ran towards the river and, to avoid that fate, jumped into the brown winter swirl and drowned as their armed pursuers watched them from the riverbank.

The legal issues in the trial had not been dealt with before and the responsibility on all of us was considerable to ensure that the accused received a fair trial. And of course the jury would be required to deal with the enormity of what occurred and the shocking factual evidence: for example, photographs of the young man who had been dismembered with samurai swords.

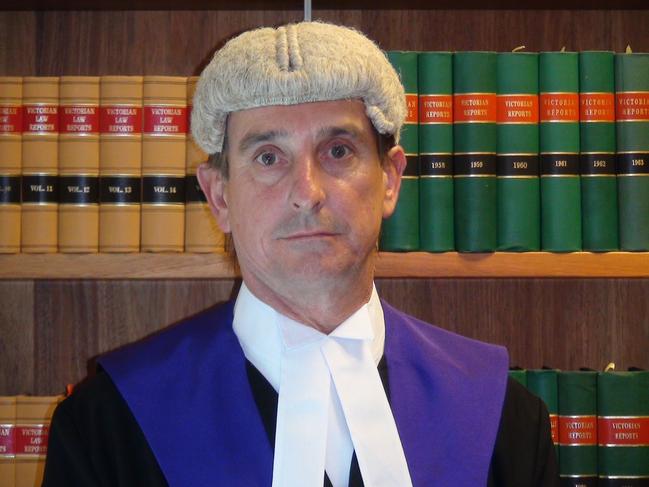

All of the police and lawyers involved in this case were experienced, capable and committed to the judicial process. The trial judge was and remains an eminent lawyer, with exacting standards that we were all required to meet. Every day of that eight-month criminal trial involving seven accused and a triple murder was driven by those standards and we all did our very best to meet them.

It is not possible to accurately measure the impact the case had on the individuals involved in it, and in particular the jurors. At the conclusion of the trial all accused were found guilty of all charges and sentenced to varying terms of imprisonment. A number of the convictions were overturned by the Court of Appeal.

When the trial finished I went surfing but, before I left, my co-counsel suggested we both have a full medical check-up. His view was that while we were both young and fit – I was 48 and he was in 30s – we had endured so much stress and pressure that maybe our bodies had reacted to that. I thought I was OK and went on a surfing holiday, but when I got back I took his advice.

The GP was co-counsel’s GP; I hadn’t met him before. I rocked up to the appointment, tanned and refreshed. He checked my vitals and then said I’ll take a PSA (prostate-specific antigen test) too. I said I don’t have any symptoms and I’m young, so is that necessary? He said we can get a baseline and it’s a guide to how your hormonal and testosterone levels are. OK, fine.

That test saved my life.What caused my hormonal and testosterone levels to skyrocket and cause a tumour remains a medical mystery. But I think it was the trial.

I was sitting in the carpark at the supermarket in Lorne when the GP rang. He told me my PSA at my age should be less than 2ng/mL as I recall and it was now 18. He told me I had aggressive prostate cancer.

The day before all this I had visited my mother who was dying in hospital and she asked me what was wrong with me? A mother’s eye? I said “Mum, I’m fine”.

So I had other tests and tried to persuade myself that I had just got an infection surfing at a break in the Maldives opposite a jail, or my body would reset after the Salt trial, or the heavy antibiotics I was taking for the infection would fix it. None of the above. After a biopsy it was confirmed. Prostate cancer at 48. Very high PSA. Poor prognosis. One urologist at the Alfred hospital told me, by phone, that I would die in the short term. I can’t remember his name.

I left my own GP, thanked the GP who did the test and found my way to a new medical team who practise a combination of mainstream and complementary medicine.

Before my treatment I was in the gym and doing Pilates every day for a month. Men have a pelvic floor too and mine was going to get a shock.

It looked as if fatherhood was behind me (I already had two children) but I didn’t know what was ahead, so I made a deposit at the sperm bank before the operation. Donating at the Andrology Department wasn’t really part of my life plan but there you go.

First up was the robot. My prostate was removed at the Epworth Hospital by a robot in one of the early examples of that procedure. The robot did its job via small incisions and today I don’t have any scars.

Well, not on my abdomen.

I had a bag for urine for two weeks or so and the removal of the catheter was a form of pain I can’t adequately describe.

I stopped work and the medical team advised me to commence a series of supplements to support my immune system and I have been taking resveratrol, CoQ10, fish oil and selenium among others for 20 years or so. The team also advised me to find a way to relax that didn’t involve drinking wine. So I went to an ashram in Hawthorn, meditated regularly and kept a journal. I still have the Buddha that was beside my bed as I recovered.

When it was time to go back to work four months later I was still passing blood as my system healed and in truth I was sure I was on the way out. I took a brief to defend a young guy charged with murder and the case went very well, but nevertheless he was convicted. It was my first trial since Salt.

It is not possible to fully understand how the diagnosis of a terminal illness will change a person’s life if they don’t, in fact, die as predicted. In my case, the diagnosis was accompanied by the death of my mother, my father and a very close friend within six months. I was surrounded by death and the final time I saw my friend as he was dying, he shared some intensely personal information with me that made me reassess my own life.

I couldn’t make any sense of what was happening around me. I had a loving family, beautiful children and a career with unlimited prospects. But in my will to survive I became overwhelmed by self-destruction. I was convinced I would die young and decided to live life to the fullest without really understanding what that meant. And so over two or three years I destroyed everything around me, leading to the breakdown of my marriage as, paradoxically enough, I overcame cancer.

This is an altogether too common story. For many of us, trauma begets more trauma.

I’m not trying to excuse the harm I caused to those who love me. But I am a person who has grown up with trauma and so when my baseload was flooded I had no pathway to manage it.

And then in 2010 I became a judge.

The judiciary in Victoria is well paid and well supported. As with all institutions, corporations and organisations, emotionally intelligent leadership is a vital component to the success of the entity.

This is a complex matter in a court and the great chief judge Michael Rozenes was the personification of leadership at the County Court of Victoria. He understood the enormous demands of the job and that individual judges have individual needs. His door was always open to me and he gave sincere, honest and frank advice to all the judges of the court. He would never gaslight a judge. I look back on my days working for him with pride. And cancer was a distant memory.

After Michael’s retirement from the court in 2015, I sensed a change in my engagement with my role. I was the subject of adverse comments by the Court of Appeal in two matters, although the convictions were not overturned. The pressure mounted and so in 2019 I decided to have a full medical examination. The GP, not my own GP but a practitioner appointed by the court, told me that my prostate cancer had returned. This was 14 years after the first diagnosis. It seemed obvious to me that the increasing burden of the work at the court had again triggered a hormonal response in me. I have biochemical recurrence.

The urologist I consulted told me that there is much that his profession does not understand about my illness or its causes. The numbers were not extreme but my body chemistry was out of balance again despite the supplements and the generous leave entitlements I enjoyed.

For the next three years I worked with the Covid impact on us all and underwent scans and tests to determine if the cancer was spreading. It was not detectable apparently but it was there. Somewhere. I had no doubt that stress was again the cause.

In 2022, I retired from the court and took up restoring the lands at my home in the Macedon Ranges. There was much to do. The previous owner, a GP, had died of cancer and as his life ebbed away he and his wife were simply unable to keep up with the jobs that had to be done.

My treatment for cancer comprised watching and waiting, working outside and growing my own food. I missed the intellectual stimulation of legal work and returned to the Bar for a while, but it was not the right path for me or my health. And so it was back to the farm with an increased determination to heal and grow. A privilege I am only too well aware of now.

In a convoluted way, I arrive at the rationale of this story.

Everyone is surrounded by cancer. My dear friend Pete, who worked here with me at the property for four years, died two weeks ago. Pancreatic. This story is for him. A neighbour from my days in Melbourne has recurrent melanoma. Another friend in England has secondary liver cancer. Half of us will get cancer. I don’t know what the relativities are to days gone by, and no doubt many people died with undiagnosed cancer then. But we live in such fraught times that our bodies are reacting too.

Which brings me to Elle. I was appalled at the pile-on when she disclosed that after breast cancer surgery she had declined chemotherapy and focused on her wellbeing. Her decision about how her wellbeing is best served is a matter for her, not an opinion writer. In the case of my sister and my brother-in-law, I observed pointless costly treatment and the suffering caused by it. Had they simply focused on their wellbeing as they left this life I have no doubt that their passing would have been happier for everyone. Elle was right to follow her path and she is alive to tell her story.

In the carpark at the supermarket today I saw a sign on a car that read “F..k Cancer”. I have seen the sign around on a few cars. It lightened my mood.

I’m fit and well now and the farm keeps me busy but soon it will be time to have another set of scans and tests. I loathe being in the machine. The scans themselves are so traumatic. Such a big device to look for something so tiny and lethal.

My friend with melanoma texted me from a recent radiotherapy session of hers with a pic of the John Olsen tapestry at Peter Mac cancer hospital. As she so wisely said “we are just a collection of cells” and Olsen depicts that so well.

As I sit here now watching the summer rain replenish the paddocks and the gardens, it occurs to me that life has become a commodity. We purchase it in our respective ways and expect or hope that success and security will insure us against its challenges.

Today as I drove out of the supermarket carpark, I thought maybe there is an afterlife and when I arrive Pete from the farm will be there asking me how the property is going as well as trees we planted together near the creek.

Mark E Dean KC is a retired judge, writer and farmer.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout