My secret truths as a stay-home mother

I turned my back on a legal career with a big law firm because I wanted to be home with my kids. If someone had offered me a heap of money to return to work when they were babies, I would have said ‘no thanks’.

Reading that took me back to a conversation from my late 20s. Some girlfriends, all young mums of little kids, were hanging about a playground by a Sydney beach one morning. Kids playing, shrieking, grubby little mouths and dirty feet, one kid probably crying because there is always a kid crying.

The young women spoke in hushed tones, swearing each other to secrecy. We agreed never to tell anyone quite how much we loved staying at home caring for our noisy, messy, beautiful little children. The pact was a joke. But only partly.

We knew better than to rave in public about loving being stay-at-home mums – for two reasons. Hanging about playgrounds, wiping little noses and hands and bums wasn’t what we were meant to be doing after graduating from university with fine degrees, suiting up and working hard for big flash law practices and other professional firms. The other reason was we didn’t want our husbands edging us out of a role we loved.

I turned my back on a legal career with a big law firm because I wanted to be at home with my kids. If someone had offered me a heap of money to return to work when they were babies, I would have said “no thanks”. That’s not for me, that’s not what we want for our kids. So I stayed home, had help with the kids, worked from home and earned less.

There was nothing false about these choices. Nothing coerced or unpleasant, which is the underlying message in Smith-Gander’s claim about false choices.

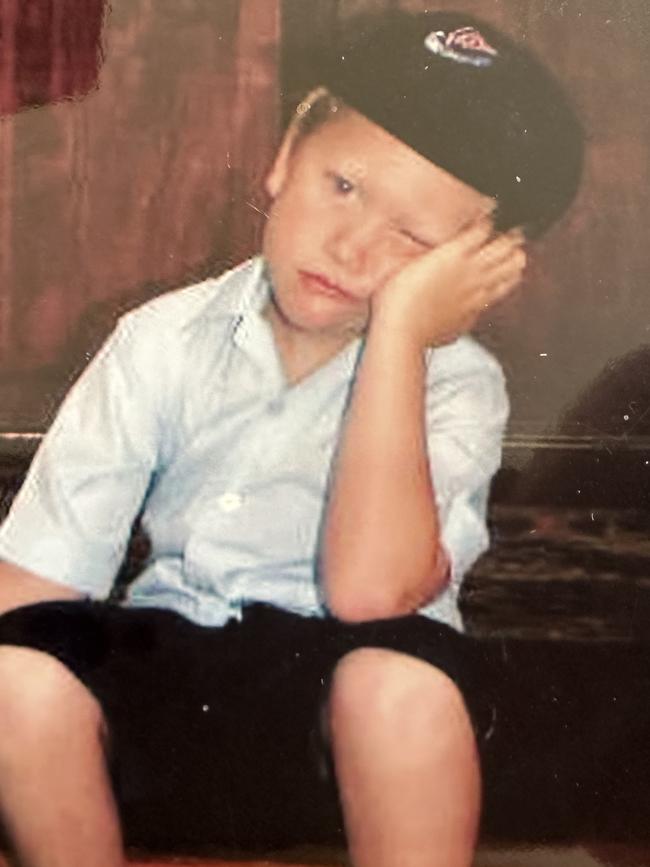

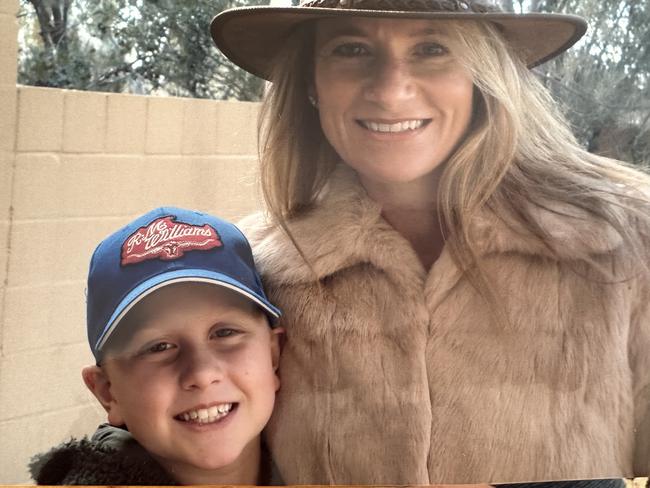

Some years later, I was encouraged by a senior politician to stand for a safe seat in politics. It was flattering. I had the full support of my husband. But I decided against that, too. I didn’t want to be a member of a political party. More important, my kids were moving into their early teens and while they most assuredly didn’t think they needed me at home, I suspected they might. I didn’t want what the books call “quality” time because you can’t pick and choose those moments when kids need you most.

So I remained at home, writing, managing work and deadlines, and being there for the quotidian challenges and enchantments of children pushing the envelope in different ways.

One afternoon, racing to finish some work at home in my office, one child kept coming up behind my chair with questions about sex. That was the inconvenient moment she picked for The Talk. I was busy, so to tide her over I plucked from the shelf beside me a book that I had bought months earlier in anticipation of this moment. The book was possibly meant for an older age bracket. Being a fanatical reader, she appeared to devour it faster than she did Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. Soon enough she was lurking behind my chair again, seeking clarification, stumbling over a big new word from one of the later chapters that I wrongly assumed she wouldn’t get to so soon. I wished my office was not at home.

I was far from the perfect mum, but that’s not the point. Each of us makes deeply personal decisions, tweaking this, changing that, as the years go on. We fumble through, mostly doing our best, in the belief that the decisions we make to work or look after kids, or both, are the best ones.

There are many trade-offs, of course. If we go to work, we miss out being at home with children. The more time we spend at home, the more we trade from our working lives. The sliding scale doesn’t render our decisions any less free, informed – and thrilling.

Many highly educated women I know started out in interesting, well-paying jobs, on paths to stellar, clever careers, but chose to step away. Working long hours in big professional careers, jumping on planes maybe for a meeting here, a meeting there, eating croissants on International Women’s Day with like-minded women, nannies for during the week, and on weekends, is not for everyone.

Many women, including me, would rather wipe the bums of many babies than live like that. My choice to alter the trajectory of my career, trading potential professional success for raising kids, was a no-brainer because raising three children will always be, for me, life’s greatest success.

Not every woman can choose to stay at home with their kids. I freely acknowledge my good fortune in being able to make my choice. There are many women for whom the choice to stay at home to care for little children is much more financially difficult than it was for me. But to demean any of these choices as false is obnoxious paternalism. It’s also deeply insulting to women who would have loved to have had children and would have loved to have stayed home to care for them.

So why does Smith-Gander presume to speak for women? How can she and her ilk possibly know about our lives, our personal decisions, our deepest desires, what we value? It is terrific that this high-profile corporate woman has risen to the top of her chosen fields. Given Smith-Gander is older, perhaps she experienced some big and nasty hurdles to get there. Good on her for pulverising them. I have nothing but respect for her choices. Her views about stay-at-home mothers, well, that’s another matter.

How great it would be if respect were reciprocated. Instead, there is an underlying assumption that caring for kids is a second-rate job, a forced and false choice. It’s a common affliction among gender ideologues to perpetuate miserable generalisations. Their message is that caring for kids is a burden. They never, ever talk about it as a prize.

The Albanese government’s National Strategy to Achieve Gender Equality discussion paper, from the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, devotes a chapter to women who “bear the burden of care”. The joyless language perpetuates this idea that caring for little children is a rotten choice. It asserts that “patterns of care” are “generally driven by social and economic structures that reflect and reinforce gendered care norms”. Nowhere does the paper mention that many women desperately want to stay at home to care for children. Norms be damned. Many of us make that choice from meandering paths.

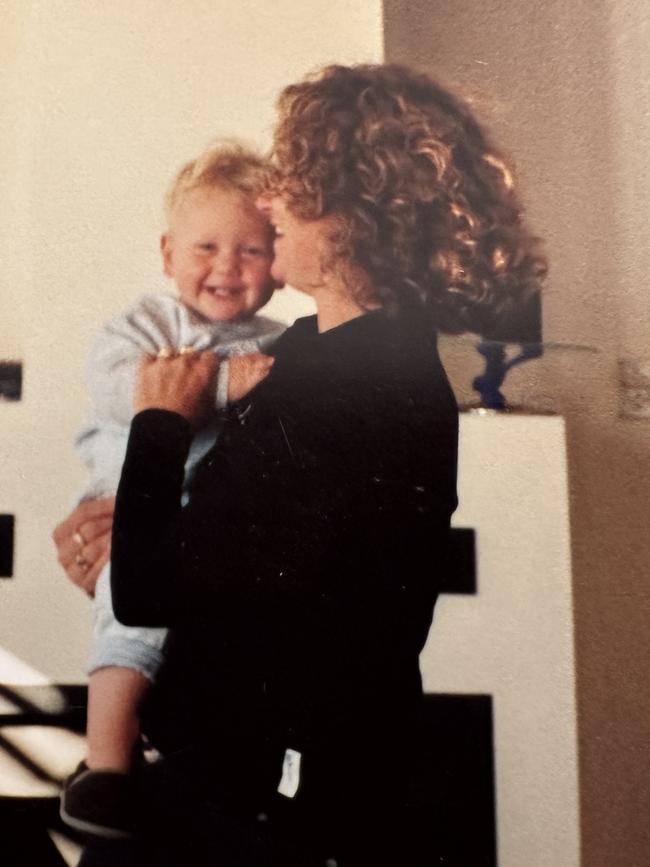

I wasn’t mentally prepared to fall pregnant at 27. I thought I had a lingering stomach bug. I fainted with shock when the petite female doctor told me it was a baby. For months I could barely say the word pregnant. I was annoyed at these foreign big breasts that arrived many months before the baby did. Why the rush? My reticence turned into a fierce desire to stay at home to care for our kids.

For some, the deep, primordial tug from a newborn child defies ideology and ambition. It can’t be measured in dollars. We are bombarded with the work side of the equation: we are told women need to work to maintain an identity, to exist on equal terms with men, to support the family and to maintain their own financial independence.

But the culture of “I work, therefore I exist” denies the falling in love with baby so central to most women’s experience. I would have fought off my husband like a banshee if he’d said he wanted to stay at home and care for our kids. He did stay at home for many, many weeks, and those periods were some of the most special times of our lives.

There is a misery to the views of Smith-Gander and other gender ideologues that is untethered from the privilege and pleasure of caring for kids. The ideologues pine for a wretched world where men and women all work exactly the same way and every workplace is made up of equal numbers of men and women, and women’s choices to live differently are demeaned as false.

The other glaring omission from all these discussions about women and work is the wellbeing of children. Back in 2017 there was a kerfuffle when American psychoanalyst Erica Komisar published Being There: Why Prioritising Motherhood in the First Three Years Matters. As The Wall Street Journal reported at the time, one agent told her they wouldn’t touch a book like that. Conference organisers disinvited her because her book, they said, would make women feel guilty.

Alas, as a society, we still don’t seem interested in exploring whether having a mum – or dad – at home in the early years is best for a young child.

The Prime Minister’s Gender Equality paper repeats recent Australian Institute of Family Studies data showing that, as at December 2021, women in 54 per cent of families usually looked after the children, while 40 per cent of families reported equal sharing of responsibility. Only 4 per cent of families reported that a man usually or always looked after the children.

In other words, even with women pouring out of universities at higher rates than men, leaving with more degrees than men, filling the professions in equal numbers, many women continue to embrace what Anne Roiphe in A Mother’s Eye calls the “whole complicated warm messy frustrating dear and dreadful business of raising children”.

Change is afoot, of course. And if gender ideologues treasured the important job of caring for young children instead of treating it as a chore, maybe more men would choose to do it sooner.

For good reasons, Western women have spent years telling the patriarchy where to get off. Why would a man presume to know what we want? It’s time to let that go. Right now, the biggest enemy of women’s choices is a small group of professional women who have the temerity to tell women what we really want.

Is there a polite way to say “f..k the matriarchy”?

I thought we were done with misery-guts feminism. It turns out not by a long shot. This week prominent director Diane Smith-Gander claimed women were making a “false” choice to stay home to care for kids. She was quoted as saying women were being forced to make this “false choice” by taking on lower-paid work in order to care for children. She bemoaned a society that perpetuated a “gender stereotype that Dad goes out to work and Mum stays home with the kids”.