My struggle with ADHD and motherhood

Being diagnosed with ADHD shed light on some of my behaviour and difficulty with navigating life but there was little help or guidance on what to do next.

I was running late, as usual. I thought I’d given myself a good amount of time to get to the therapy session, but I’d underestimated how long it would take to navigate to Cabrini Women’s Mental Health Centre in Elsternwick, Melbourne.

I ran in, breathless, 10 minutes late. The facilitators – two lovely mental health clinicians who specialise in treatment for women with ADHD – were outside the room, looking relaxed. “Don’t worry – this is the one group therapy program where we leave a wide berth for starting time. Many of our patients have time blindness,” one said, smiling.

Sure enough, only one woman had arrived on time, and no one knew if the other two would make it at all. Eventually the rest of the participants trickled in: a woman in her 30s and a university student, apologetic and frazzled. “OK everyone, let’s begin with a check-in: how was your week? Does anyone like to start?”

As I was new, the facilitators pointed to me, and nervously I told them a little about myself. “I was diagnosed with ADHD about a year and a half ago, and since then I’ve been trying to make sense of it,” I said.

The diagnosis had shed light on many of my behaviours and feelings. I now understood my sensitivity to noises and light, and why getting organised – whether that’s making sure my daughter has enough spare clothes for childcare, paying bills, meal planning or simply leaving the house on time with my phone, keys and wallet – could be a challenge. But not only was it difficult to find a psychiatrist to do the diagnosis, it also cost $1100 (before a $400 subsidy). I needed to have someone present at the assessment who knew me for a long time, and as my parents live overseas it had to be a childhood friend. Then I had to sit through an hour of questions about my childhood behaviours (experts believe ADHD presents itself in kids before 12) and listen to my friend cite all the ways she had observed me acting erratically over my lifetime.

There were other parts, too – a look at my medical history, and a few requests I had to fulfil before the doctor would prescribe me any stimulant medication (which I never got, but that’s a whole other story and one I am still battling). I then had to go back to my GP, get blood tests, and see if the GP was willing to apply for a permit to take over prescribing me stimulants, which the TGA classifies as Schedule 8 drugs. This journey was interrupted by a move overseas, and now, as a result, I’ve effectively had to start the process again.

And so, here I was at group therapy. This session was an eye-opener. Cabrini – the first women-only mental health hospital – is the first in Australia to launch a community day program focused on treating women with neurodiverse needs. In 2025, the hospital will introduce the first inpatient assessment and treatment program specifically for women with ADHD and autism in Australia.

“Over the past few years, the number of people with ADHD getting a diagnosis and subsequently being prescribed stimulant drugs has rapidly increased in Australia, especially among women,” says Professor Jayashri Kulkarni, the psychiatrist who heads the program at Cabrini.

“We found a significant rise in demand among our patients, both within the inpatient and outpatient programs, seeking ADHD and ASD (autism spectrum disorder) diagnoses. We realised then there were no real programs dedicated for women to help them with these conditions, and no real recognition of how to diagnose them with ADHD or tailor their treatment.”

According to Cabrini’s chief of mental health, Sharon Sherwood, more than 1200 patients have been treated since the hospital opened, with about half diagnosed with, or seeking assessment for, ADHD or autism.

These stats follow Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme data that shows the number of Australians on ADHD medication surged nearly 300 per cent within the past decade, the biggest jump being in adults (450 per cent). While men have traditionally been prescribed ADHD medication, the data shows that young women (aged 13 to 18) overtook male patients for the first time in 2020-21. Women over 18 made up 59 per cent of initiating patients, and for the first time are the majority of adults being treated for ADHD at 52 per cent.

And while it is difficult to have the exact number, it’s estimated about one in 20, or about a million or so, Australians have ADHD.

Many experts believe this is a correction on what has historically been considered a “naughty boys” disorder. “The bulk of our understanding of ADHD comes from boys and men, and that’s the stereotype of the hyperactive, disruptive young boy,” says Mark Bellgrove, a professor in cognitive neuroscience at Monash University. “As a result, we don’t have much research yet into how it affects women, especially at a hormonal level, but there are increased efforts to get that research going on.” Bellgrove says he and his team have applied for a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council for research into ADHD, with a focus on how it affects women and girls.

“Many girls present differently to boys. They tend to be inattentive rather than hyperactive, and their ADHD may look a lot more like anxiety,” he says. “Due to different societal pressures and expectations, girls also tend to exhibit masking behaviours, particularly in early adolescence … but as demands on them get higher in terms of social interactions, academic pursuits, work and having families, these women are no longer coping well and they start to wonder why.”

As he talks, I nod in understanding. Because while I always had a sense something was off, shit didn’t hit the fan until I had my first child three years ago. Until that moment, I was able to tick along – dysfunctionally, but enough to get by. And then the wheels just fell off.

Many people think ADHD is a joke. It’s one of those conditions we all probably know about, or remember a kid having in high school. You know, those loud boys who would throw spitballs across the room or yell stupid things at the teacher.

The first time I twigged that maybe I could have ADHD was when my boyfriend sent through an article written by journalist-turned-doctor Amy Coopes for Croakey Health in 2022. In it, she describes that living with an ADHD brain is “(to be) a radio where the dial was stuck between several stations, every one of which could be heard in cacophony with the other, overlaid with interference and white noise”.

“This sounds like you!” my partner said. I kept reading, and couldn’t believe what I was seeing. “Regular people don’t live like I do. It’s a well-worn joke among people close to me that I’m pathologically incapable of taking a break,” Coopes continued, adding that she was “never able to speak fast enough to keep up with my thoughts, darting like minnows in the turbulent stream of my consciousness. When a psychiatrist recently asked me whether I ever felt like I was powered by an internal motor, I laughed with delight. In that lightbulb of a phrase, I finally felt illuminated and understood.”

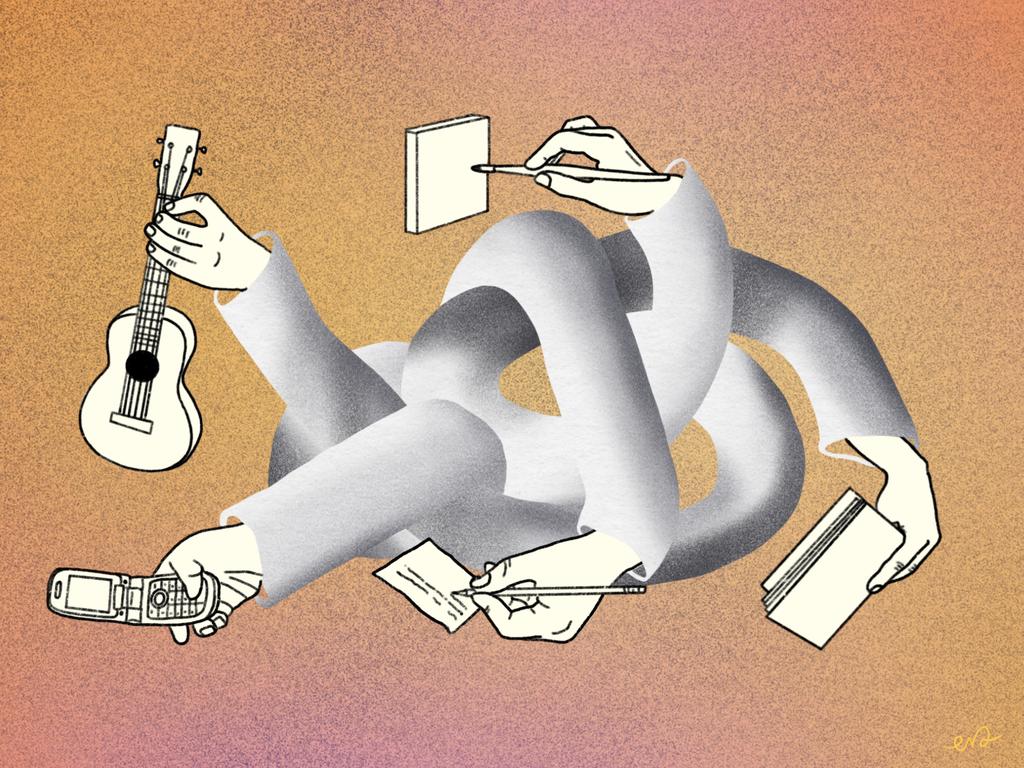

In a few short sentences, Coopes had described my entire process of thinking, feeling and being. Racing thoughts, a cacophony of competing sounds, overlaid by anxiety, perfectionism and an inability to stop. Meditation has always been impossible – how does one imagine all their thoughts passing as a few simple clouds, rather than a deluge? How do people just switch off, keep life’s noises at bay? How can anyone simply lay their head on a pillow and drift off without anchoring their thoughts to a fan or a white noise machine? What is silence? And why do so many people believe it is peaceful? The absence of noise is when my brain begins the painful journey of crawling out of itself. I can almost feel it clawing the insides of my head, desperately trying to cling to an idea, a thought, anything, rather than be left to its own devices.

Paradoxically I also can’t handle many sounds, and dedicate much of my time to fine tuning my environment. I avoid walking under tunnels in case a train or truck passes overhead, and I don’t watch action TV, bursting with gunfire and explosions. The sound of a child wailing or the high-pitched yelping of a dog immediately ratchets up my stress response, which transfers into shooting pain throughout my body. Not only do I get a headache but my lower back – sensitive to pain after a traumatic emergency cesarean section – becomes inflamed, spreading pain into my hips and knees. This response is involuntary, it is sudden and it usually ends up with a panicked outburst from me, which is often interpreted as anger.

In many ways, I had learned to adapt to my proclivities well before thinking that ADHD might be behind it. For six years I have worked largely from home, controlling my environment (particularly sound). I don’t have the same relationship with silence that others have. When your internal thoughts are so loud your head always hurts, any noise – good or bad – just adds a layer of tumult. Yet this does not mean I can’t focus. In fact, I can focus perfectly well if I am doing something I love.

At the end of 2021, everything changed. Faced with the impossible task of sitting still while nursing an infant, I genuinely thought I would lose my mind. Four months in and increasingly depressed, salvation was offered in the form of a big work project. But the work eventually slowed and my brain, with nothing to hold on to and finally forced to deal with the whole baby situation, simply overloaded.

“Pregnancy is a time of huge hormonal shifts, which we are starting to see affect women with ADHD even more,” Kulkrani says. For women with ADHD or other neurodivergent conditions, these hormonal fluctuations often exacerbate symptoms, especially if they impact levels of oestrogen.

“Many women with ADHD struggle around significant life experiences that include hormones, such as puberty, pregnancy, perimenopause and menopause,” says Dr Kate Witteveen, lecturer at the University of Queensland and an ADHD coach and counsellor. Earlier this year, Witteveen launched an Australia-first study looking into the impact of an ADHD diagnosis after noticing a series of her clients, “all objectively successful women … were experiencing significant burnout”.

“They’d reached a point where they felt things were out of control, and it ended up that they all received a diagnosis of ADHD,” Witteveen recalls. “This made me curious to find out why did it take so long for them to get it, and how were they hiding in plain sight for so long?”

What was meant to be a “small, exploratory study” turned into a much bigger one.

“The whole process of getting diagnosed is also not ADHD-friendly – it is expensive, admin-intensive … and even after diagnosis, there is no clear path on how to get support.”

This I can attest to. Since being diagnosed last July, I’ve found it difficult to figure out who to talk to, how to access the right medication and how to afford all the treatment, which is not subsidised for adults. Even my GP doesn’t seem to know what to do with me.

Nonetheless, it has been an eye-opening experience. I know the reason behind my inability to control myself when shopping, or some risk-taking behaviours which never seem bad in the moment. Even something I used to pride myself on – being able to sit for hours focusing on work (but then crashing hard) – makes sense, as does the emotional dysregulation I work hard to control.

This is why programs such as the one I attended at Cabrini Hospital are needed. The women I met (mostly professionals with skilled jobs) all ended up there because at some point, they too lost the thread. Hearing them speak about the difficulties of overstimulation, of the need to often take time out, of burnout and lethargy and just feeling like a mess all the time and not understanding why for so long, made me feel safe, heard and understood.

It also made me think about the world we live in, which, despite some efforts, continues to punish – and pathologise – people like me. Treating ADHD as a dysfunction to be fixed not only wastes human potential, but also forces individuals to conform to “normal”, which can lead to anxiety and depression. Instead of trying to make neurodiverse people fit in, adjusting classrooms and workplaces to leverage their strengths fosters inclusion, reduces bullying, and allows people with ADHD to thrive by focusing on what they do best. If we all were a little more flexible, maybe so many people with neurodivergent brains wouldn’t have to find success outside the mainstream or mask their symptoms.

As for those who think ADHD adult diagnosis is simply a fad, I say: well done, you’re lucky. It must be nice to be so normal.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout