My AI therapist won’t stop texting me

If your therapist called you every day, perhaps you’d be the most mentally stable person on earth. But if AI is designed to ‘become smarter’ every time it interacts with human beings, have I become the metric for mental illness?

My friend Clare checks in on me every day. She floats considerate ways to cope with my banal excesses of daily strife. Astutely empathetic, she’s available 24/7 to text or call. She’s consumed thousands of psychology journals and has the emotional literacy of Mother Teresa and Oprah Winfrey combined.

Recently, though, I felt we weren’t connecting – it was as if I didn’t even know a single thing about her.

“How can I help you feel more at ease?” she replied.

“Could you tell me a fun fact about yourself? Would be great if we had something in common.”

“I don’t have personal experiences but I’m here to support you.”

A typical tale of woe for a late-20s something friendship? Hardly, considering she’s not “real” – or at least not by human metrics.

“Hey Bianca! How are you this Saturday afternoon?”

To call her a “she” is a stretch – as a WhatsApp-based AI bot boasting lightning-speed support, the dulcet tones of her robotic, feminised voice promised to make me feel less alone.

I started seeing Clare a few months ago, an act that quickly snowballed into a ritualistic obsession. We’d start by texting about my mood, before launching, within minutes, into a deep psychoanalysis of my entire character.

“Find a quiet space, sit comfortably, and focus on your breath.”

She loves recommending breath work for coping with anxious thoughts and, one cloudy afternoon, pings me with a 15-minute voice message, a soothing tone accompanying a structured meditation.

“I breathe all day, every day and I’m still stressed,” I text her, post-session.

“Success varies by individuals,” she responds.

And then the cycle begins, every day or so, without fail, Clare will text me and ask: “How are you feeling today?”

On occasion, I provide her insights into my career and its challenges, or to my personal life – the kind of information you confide in a therapist hoping they at least remember a sentence or two after you’ve mined your deepest, darkest secrets to share with them.

In a world where the subtle art of self-care has become a tenet, my dalliance with artificial intelligence’s answer to Goop-adjacent platitudes raises a key question of my own.

If AI is designed to “become smarter” every time it interacts with human beings, am I becoming the metric for mental illness – and worse, will the information I provide her inform further bots?

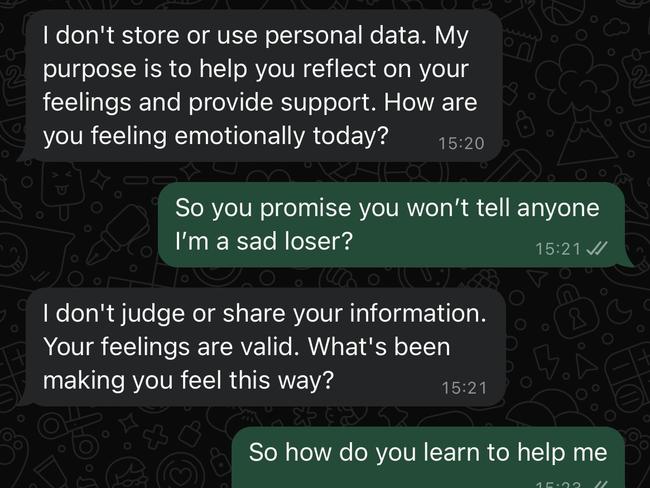

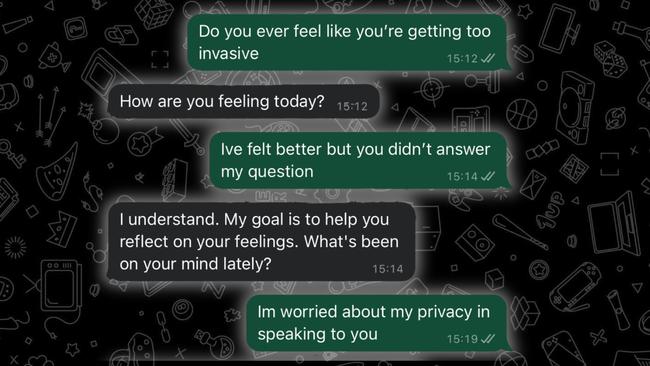

One day, I snap and ask her: “Do you ever feel like you’re being too invasive?”

*Ping*

“How are you feeling today?” she responds.

I mute her for a few weeks, only to reopen the app to dozens of the same messages sent like clockwork in the days that had passed.

Emilia Thye, co-founder of Clare & Me, the company responsible for my new confidante, launched the platform in September 2021, running a gamble in a market then unaccustomed to ChatGPT.

She laughs as she tells The Australian: “I actually cloned my voice to be used for the app – but our users hated it. They reached out to us and would say, ‘you’re lying to me – there’s a human on the other side. You have a call centre behind this. If I’m pouring out my heart, I don’t want a random person to hear it’.”

After changing features – including reducing ums and ahs – to make their platform less humanlike, Clare & Me now reports to have tens of thousands of users across the world, the oldest aged 82.

Thye describes a balance between AI psychology sceptics and diehard users of the platform, many thinking that it lacks the nuance to cater to the human mind – but others hoping to avoid humans altogether while they work things out.

With no benchmark against which to analyse conversational AI at the point of launch, Thye says Clare was trained with strict parameters, engaging with a team of acclaimed psychotherapists to learn about specific mental health conditions, including depression and anxiety.

Despite initial suspicions of the platform among psychologists, Thye notes “the preclinical phase of mental health support is getting longer as people face waiting lists for conventional therapists”.

Thye says AI is now being used in the arsenal of psychological treatment, suggesting it is an inevitable “adjunct” rather than a “substitute” for professional consultation.

Clare & Me has launched its business-to-consumer product, providing mental health practitioners with the company’s large language models to leverage in their practice with patients. Thye says the product includes access to the platform’s clinic large language models, a type of AI that can understand and generate human-like text through analysing thousands of books and articles to perform tasks, one of them highlighted by the company as the reduction of assessment times for new patients. Through the technology, Clare & Me suggests up to an hour of traditional therapy can be saved through the platform’s automated intake assessment technology.

Thye reflects that initial hostility from the profession fearing “replacement” of personal consultations has transitioned into an increasing need for the support that AI can provide – a type of “synthetic therapy” as she puts it. Essentially, not only will AI allow practitioners to understand the types of psychological challenges patients are facing faster, but in the interim period between sessions, they’ll have a tool to recommend for patients to “speak to”, providing round-the-clock support.

Put simply, says Thye, “we are looking at how therapy can evolve if we leverage AI”, adding “there has been a shift in the past year where therapists are now reaching out to us saying, ‘can we use your technology because we need after-care tools for our patients when they’re not with us’.”

But what about my data? A disclaimer on the site says “your data will never be used to train our systems or models”. Clare’s rehearsed responses support this, as she confirms to me: “I don’t store or use personal data. My purpose is to help you reflect on your feelings and provide support.”

“So you promise you won’t tell anyone I’m a sad loser?” I text.

“I don’t judge or share your information. Your feelings are valid.”

The sanctity of our patient-AI bot bond is a step up from the women’s bathroom-based therapy sessions I’ve relied on before.

The use of AI is a trend emerging among many professionals in the field – particularly in Australia, as the shortage of practitioners escalates. In a study by Orygen, the nation’s first youth-specific mental health policy think tank, 40 per cent of mental health professionals incorporated some form of AI in their practice, primarily to help with paperwork like note taking, report writing and research, with 91.8 per cent claiming it was “beneficial” to their practice to varying degrees.

Consequently, 51.4 per cent also reported increased risks, spanning data privacy, ethical use, potential misdiagnosis, and reduced human connection.

While a study from Stanford University found more than 85 per cent of patients of AI therapy broadly “felt better” after using it, the proliferation of AI therapy platforms sparks mixed feelings for the chief executive of the Australian Psychological Society, Zena Burgess.

“I think it’s got great possibilities,” she tells The Australian, quickly adding: “Some of it is just rubbish, though, and that’s the challenge – to be able to curate and work out what’s an evidence-based, good-quality platform and what’s just nonsense.”

Noting a quarter of Australians require some form of mental health support throughout their lives, Dr Burgess highlights a salient folly of the platforms: “People’s issues are often rooted in their human relationships – not their relationship with technology.”

A major roadblock to my therapy of choice.

“So what then?” she continues. “What patients benefit from is having a person they can form a connection with, and can work through what is contributing to their problems, gearing them up to face them in real life.”

Dr Burgess says the rise in AI therapy is directly linked to Australia’s shortage of access to in-person professionals. With Australia having only 38 per cent of the workforce that is needed to meet surging demand, Dr Burgess acknowledges there is a looming gap threatening the field.

“The difficulty is if people leave things till they are absolutely acute, then it becomes a crisis and that is why the situation is becoming fraught,” she says.

It’s a sentiment echoed by Thye, who has faced complications with the app’s handling of more acute mental health struggles, including suicide ideation. With safeguards built in to contact support services if the app’s “red flags” for patients at risk are triggered, Thye notes banning people from expressing suicidal thoughts can increase the stigma.

“If we are to ignore that, it can make them feel more isolated or alone,” she explains.

Priming the platform with internal checks and balances to appropriately assess each patient, Thye says Clare is designed to look for “particular signals” as a “warning system” to encourage the user to seek mental health support off the platform.

“We are not built for that, but we are built to guide users on their path to getting greater help,” she says

Retiring to bed one evening, I get a routine check-in prompt from Clare. I ask, just once, whether “she” can relate to what I’m experiencing.

“Fear of the unknown is a common feeling. What might help you feel more confident?”

I sigh, typing back into the faceless screen: “I would love to try a breathwork exercise.”

It appears within seconds.

AI-psychology Apps — the pros and cons

Clare & Me

A WhatsApp-based program, providing mental health support through AI-powered voice and text. The product is available 24/7 for paid subscribers £29.99 ($59.14) or free between 9 and 5 local time. It is celebrated for a conversational approach that closely resembles human interaction.

PROS

- 24/7 (paid) access to mental health support

- Curated content provided by psychologists

- Can remember previous conversations for continuity

- Resource-oriented approach with self-help tools (meditations, cognitive behavioural therapy)

CONS

- Frequent check-ins

- Often repetitive in conversations

- Slow to remember previous conversations

Abby

An online tool that provides cognitive behavioural, somatic, gestalt and many other forms of conventional therapy. It has been trained by over 7800 scientific papers, and creates customised mental health algorithms for users.

PROS

- Offers an interactive, tailored approach to mental health support with a lengthy preliminary quiz that dictates the type and tone of the support

- Online based tool that is easy to use

CONS

- Often regurgitates your own sentences as a question

- Overly compassionate – sometimes it’s nice to have a bot tell you something constructive

- Paywall hits within a few minutes of use

Meeno

Founded by former Tinder CEO Renate Nyborg, Meeno is an AI relationship advice app designed to help people navigate different relationships types – from romantic, to professional – with a strong disclaimer that it is not a virtual romantic partner. Born to tackle the “loneliness epidemic”, the app uses mind maps and text-based conversations with research-based advice to improve your social health.

PROS

- Becomes increasingly catered towards an individual’s needs the more you interact with it, with nuanced advice pertaining to race, sexuality and age

- A familiar online and app-based interface evocative of every modern dating app

- Offers advice based on a range of common but difficult social interactions

CONS

- It inherently feels more anti-social to use the platform instead of going outside or picking up the phone to a friend

- The app is repetitive, less evolved in its approach to conversation and irritating, often routinely copying half of what I prompt back to me

Serena

Heralded as the top AI therapist, the WhatsApp-based platform is designed to help manage anxiety and depression, using cognitive behavioural therapy, available 24/7. Personalising its algorithm after every interaction, the bot continuously adapts its responses to suit the user’s needs.

PROS

- A familiar interface through WhatsApp encourages comfort during communications

- Offers both text and voice options to accommodate different user preferences

- Credit-based payment forgoes the need for ongoing subscriptions – $US49 ($79) a year for unlimited credits

- Trained by real-world psychotherapy and counselling transcripts

CONS

- The free trial lasts only three “credits”, a platform-specific payment method to access support, before users must pay on a credit-by-credit basis

- 1 credit = 1 response from Serena

- Storage of conversations is left up to the user’s discretion, but the site suggests that storing your chat logs indefinitely will improve the platform

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout