Public health systems are on the brink, and it’s time for transparency

Cracks in the public health systems are bleedingly obvious, and can no longer be ignored.

Australia is often described as having a world-class health system. There’s no doubt that we do. But in our public hospitals, the pursuit of excellence comes at a price. That price is often invisible to patients; though sometimes the cracks in the system are bleedingly obvious.

For patients, the system pressures are manifest in excessive wait times, too speedy discharge, or for the very unlucky, lives ebbing away in the back of a ramped ambulance.

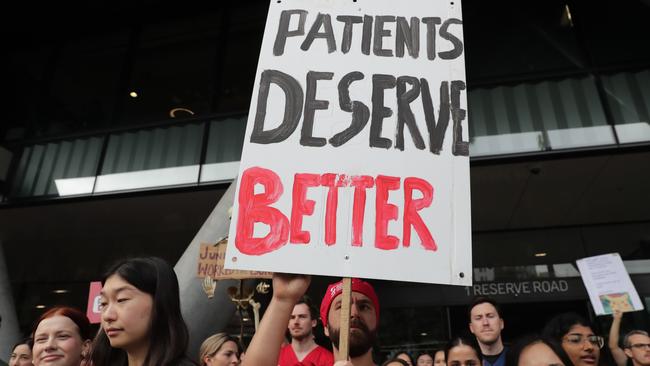

The trends are accelerating. On a widespread basis, doctors have had enough. They are overburdened, despondent and scared.

The Australian this week launched an investigative series, which we have dubbed Life Support, to explore what is driving the huge pressures on Australian public hospitals. What is at stake is not only clinicians’ welfare as public health systems teeter on the brink. Also at stake is patients’ health – and their lives too.

In England, the Starmer Labour government has moved to dismantle the National Health Service’s administrative body, NHS England, which manages health services across the country, slashing the jobs of half of the agency’s workforce. NHS England is a body tasked with doling out money to the NHS’s network of hospitals and primary care clinics according to executive instructions. For the past 15 years, it’s been given a large degree of latitude and independence, but it came at a cost of increasing duplication and bureaucracy. Patient safety scandals have been documented with alarming regularity.

Current or former staff in public hospitals or patients can contact Natasha Robinson by email at robinsonn@theaustralian.com.au or by Proton Mail at health_editor_australian.proton.me

Though Australia’s federation has no equivalent of England’s nationalised health service, with devolved management of hospitals in most states, doctors working in Australia’s public system believe many of the ills of the NHS are also present here, especially in terms of workplace culture and interrelated threats to patient safety.

There comes a point when clinicians can no longer live with themselves when forced to work in unsafe systems. It’s become clear to many doctors and nurses in public hospitals across Australia over the past decade that changing systems from the inside is next to impossible.

Increasingly, they refuse to stay silent.

“This is a volcano which may well erupt,” says Dr Deborah Yates, who worked in public hospitals in Sydney for 25 years before abandoning ship, broken and grief-stricken, after treating the disadvantaged for decades.

The recent psychiatry dispute in NSW, in which half the workforce of staff specialists handed in their resignations, was a harbinger of just how fed up many sections of the public sector workforce are. That was followed in NSW by a three-day strike by doctors across the gamut of specialties – something that hasn’t occurred in the state in more than three decades. But it’s not just a NSW trend. Governments and administrators in all states are doing their best to keep the real state of public hospital breakdown hidden. They routinely attempt to silence the doctors and nurses who seek to expose it.

In Adelaide just a few weeks ago, senior emergency doctor Megan Brooks took the difficult decision to stare down SA Health’s attempts to silence her through its code of ethics and give evidence to a coroner about the severe state of ambulance ramping at the Royal Adelaide Hospital.

In Perth, it was frontline doctors who wore the blame for the July 2024 death of three-year-old Aliyah Yugovich, who was wrongly given an anti-seizure drug before dying of the flu. Accountability up the chain has been minimal.

The Australian next week will reveal a similar case of a doctor being silenced over a serious threat to patient safety in Queensland.

As a reporter, unpacking these matters, which are always complex but also have system-wide drivers, is difficult. There’s always the sense that however huge the iceberg, public reporting may never be enough to trigger a new direction for a ship as big as the public health system. But it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try.