One pioneered vaccinations, the other attacks them. Still, they share so much

Two medical men — one lauded by their peers, the other a hugely diminished figure addressing fringe anti-vaxxer rallies around the world — played crucial roles in the history of vaccination, albeit in very different ways.

Vaccination is a triumph of medical science. Every year tens of thousands of lives are saved and millions more enriched by prevention of disability and disease.

A World Health Organisation study published in The Lancet 12 months ago estimated that poliomyelitis virus vaccinations, the variations developed separately by Albert Sabin and Jonas Salk, have saved 150 million lives.

In recent years we have seen the introduction of human papillomavirus vaccine, which sits at the heart of a global strategy to reduce the incidence of cervix cancer – a result of groundbreaking research led by Ian Frazer at the University of Queensland.

Early in 2025 maternal vaccination against respiratory syncytial virus was added to Australia’s National Immunisation Program.

This is a parable of two men and the enormous impact they have had on the world.

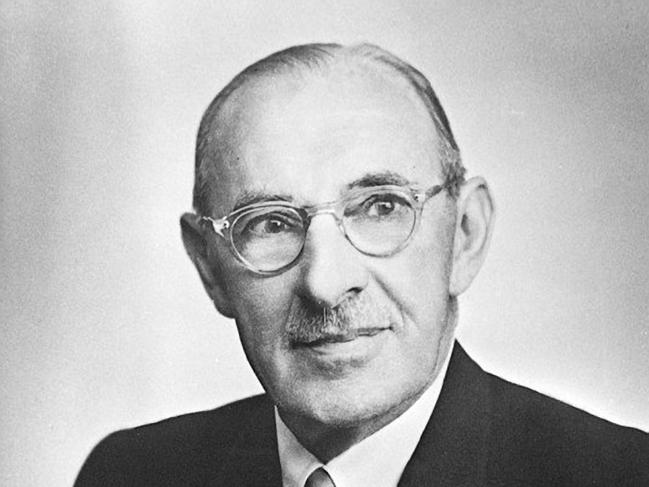

Norman Gregg was born in Sydney in 1892. He was an outstanding cricketer and scholar at Sydney Grammar School, winning a scholarship to the University of Sydney to study medicine.

Immediately after graduating, he left Australia for the battlefields of France, serving as a captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps where he was awarded the Military Cross for gallantry in the field.

On returning home he was employed as a resident medical officer at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital before training in ophthalmology. After completion of his specialist training, he enjoyed a distinguished career, dividing his professional time between private and public specialist practice in Sydney. He was awarded a fellowship of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons.

In 1940 there was a major rubella (German measles) outbreak in Sydney. The following year Gregg reported in the literature the unusual occurrence of congenital cataracts in 78 babies. Most of the mothers of these babies reported rubella infection early in their pregnancies. Gregg correctly surmised that viral infection early in pregnancy had caused the congenital defects.

A year later he co-authored a paper describing congenital heart defects and deafness as other features of congenital rubella syndrome.

Gregg was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. The award recognised his notable contribution to public health, having laid the epidemiological groundwork for the eventual development of a vaccine against the RNA virus in 1969. Tragically, this was too late to prevent 20,000 cases of congenital cataract that followed a rubella outbreak in the US in the mid-1960s.

Gregg died in Sydney in 1966, not long before the rollout of the new vaccine.

Not all careers are so inspiring.

Andrew Wakefield was born in Buckinghamshire in 1956, excelled in schoolboy rugby and trained in Medicine in London, going on to be awarded a fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1985 and being appointed to the Royal Free Hospital.

In 1998 Wakefield was the lead author of a paper in The Lancet linking the measles, mumps, rubella vaccine with a novel syndrome of autism and bowel disease. Predictably, Wakefield’s paper spiked an immediate drop in the uptake of MMR vaccination in Britain and a rise in the number of cases of measles.

The British health secretary ordered the Medical Research Council to investigate Wakefield’s claims, finding no evidence to support his work. Concerns were immediately raised about the integrity of the research. Serious allegations were made about the falsification of data.

Eventually, 10 of his 12 co-authors withdrew their support for Wakefield’s claim of a link between autism and MMR vaccination. Wakefield left the Royal Free in 2001.

After the longest investigation in its history, the General Medical Council struck Wakefield off the medical register in 2010, having found him guilty of serious professional misconduct, to have been dishonest, having acted in his own financial and personal interest, and failing to act in the best interests of children.

As observed in a subsequent appeal to the courts: “There is now no respectable body of opinion which supports the hypothesis that MMR vaccine and autism are causally linked.”

Unfortunately, the faith that a significant minority of the world’s population have in vaccination programs had been shaken. It served to add to the distress of many parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. To this day, it sits at the centre of claims made by those who, for a whole variety of reasons, oppose vaccination.

Two men, both distinguished schoolboy sportsmen, both training in prestigious medical schools, both going on to qualify as surgeons, both appointed to famed hospitals in their largest city in their country, both working in medical research. One lauded by their peers, having made a fascinating contribution to epidemiology and human health, the other a hugely diminished figure addressing fringe anti-vaxxer rallies around the world.

Researchers across Australia and the world continue work on vaccines against malaria, chikungunya, Group A streptococcus and enterotoxigenic E. coli. Their painstaking work will ultimately bear fruit.

I spend a lot of time with my vaccine-hesitant patients. It is often exhausting. But it is worth it. Sure, it could be spent addressing other areas of health anxiety or illiteracy. But it is necessary to try to overcome the harmful misinformation that spreads freely on the web and social media.

The misery and disease from those who spread anti-vaccination lies come at a cost. Doctors like me stand on the shoulders of giants such as Salk, Sabin, Frazer and Gregg. We and the populations we serve have so much to be grateful for.

Michael Gannon is a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist with 18 years’ experience as a specialist. He has delivered more than 5000 babies. He served as president of the Australian Medical Association from 2016 to 2018 and is president of leading professional indemnity provider MDA National.

This column is published for information purposes only. It is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be relied on as a substitute for independent professional advice about your personal health or a medical condition from your doctor or other qualified health professional.