The bystander effect: what would you do?

A performer collapses on stage. A person is racially abused on a bus. A crashed car with two people trapped inside is about to go up in flames... Do you stand back or step up?

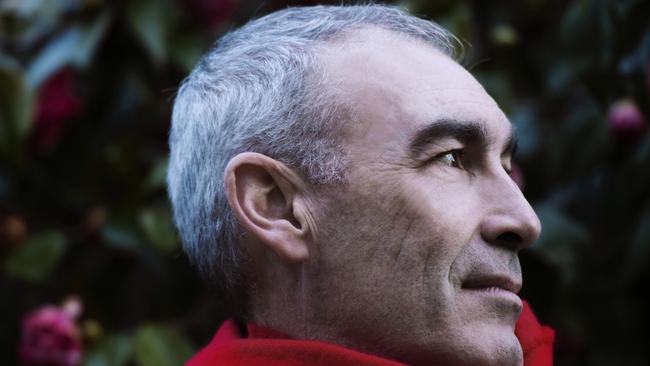

Greg Page does not remember his heart stopping. He cannot recall dropping to the floor at the end of an adults-only reunion concert of The Wiggles in January, or lying in the wings and being shrouded by a hastily pulled curtain, or the small group of people who persisted for an agonising 26 minutes to keep him alive when it seemed he had taken his last breath at 48.

Even now, half a year on, the original yellow Wiggle has only shards of memory of that summer day when the four founding members of his beloved children’s band were reuniting for a bushfire charity concert. He remembers leaving his Sydney home for the gig, but not the sound check at the Castle Hill RSL club. One of his favourite songs, The Monkey Dance, was on the set list and he remembers talking to the rest of the band about playing it, but he can’t recall performing in front of the 800-strong audience.

In the before and after sequences that have since come to divide his life, Page has a single memory of breathing heavily, and another of then lying on the floor just off stage, “and looking up at the ceiling and just feeling unwell, but not in a bad way. I just felt absolutely exhausted,” he says quietly of his cardiac arrest. “My next memory is waking up in hospital that night.”

What happened in between, he has since learnt, is an exceptional example of the kindness of strangers. Page had left the band in 2006 when he was diagnosed with orthostatic intolerance, which can cause fatigue and blackouts, and January’s concert was the first time he had performed with his old mates in years. But just as they were ending their final song, Hot Potato, Page staggered off the side of the stage. One of his main arteries was blocked, and his heart stopped beating. “The way I understand it, I basically fell at the feet of a girl named Tyra and she called in [touring manager] Luke Field and he radioed for [office staffer] Kim [Antonelli] who had done CPR training.” Antonelli began compressing Page’s chest with the help of a doctor who had rushed up from the audience.

“It seemed surreal,” says drummer Steve Pace, who heard a crew member yelling “Greg’s down!” as he finished the last beats of the song. “I rushed in and said, ‘I know CPR, I can help’ and the doctor moved aside and I was doing the compressions.” At the same time, a young woman approached a nearby security guard. From the audience, nurse Grace Jones had noticed that the yellow-skivvied Wiggle seemed unsteady before suddenly disappearing from the stage. Nearing the small group now bunched around him, Jones was handed a defibrillator which she used to shock Page’s heart three times, a move that paramedic Brian Parsell, who took the musician to hospital, later said had saved his life. “Greg is here because she [Jones] was brave enough to step forward.”

Hundreds of people were at the sellout show, but only the newly minted nurse and a few others were willing or able to step forward. “I think a lot of people in the room didn’t know what was going on. I sort of fell at the side and was quickly off stage, and the crew pulled the curtain around me,” says Page, who has spent much time, in the months since, considering the actions of those who intervened in his personal emergency. “The fact that those people stepped up to have a go at saving a life, I am so grateful. Had they not stepped in, I would be dead.” But his gratitude has been tinged with a lingering question. If he had been a witness to this event, and not its central character, what, he keeps wondering, would he have done?

We’ve all been there in varying manifestations: a stranger screams insults at a bus passenger, a colleague is sexually harassed, a stranger collapses, an athlete is racially abused from the stands. We see it happening but do we intervene? From verbal assaults to physical altercations, bullying and car crashes, the circumstances may well be life threatening, and in extreme cases, as the US has been witnessing, can lead to deep civil and social upheaval. In late May, in a case that quickly gained global infamy, Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin spent nearly nine minutes with his knee pressed into the neck of George Floyd, a former security guard who had been apprehended over the suspected use of a counterfeit $20 note. Pleading with the officer to end the violent restraint, bystanders filmed the encounter. If not for that footage, the case might have gone largely unnoticed. “Thank God a young person had a camera to video it,” Minnesota governor Tim Walz said later. Earl Gray, a lawyer for one of the policemen, criticised bystanders for filming but not physically intervening, saying: “If the public is … so in an uproar about this, they didn’t intercede either.”

While all these circumstances vary, they share a core conundrum. You witness something bad happening to someone. What, if anything, do you do? The answer in many cases is nothing. “We are programmed to be cautious,” says psychologist Catherine Sanderson, whose new book The Bystander Effect examines the psychological factors that underlie “the very natural human tendency to stay silent in the face of bad behaviour”. Often our first reaction is to just keep walking. “We are, I think, hardwired to want to fit in and sometimes that leads us to not do what we should do,” says Sanderson, chair of the psychology department at Amherst College in the US. “Sometimes we think that person we help might think we are overreacting or it will embarrass them.” Or us.

Radio host Liam Stapleton found himself facing the same dilemma – to speak out or not – when a passenger was being racially abused on a bus on which he was travelling last year. “It’s that gut-sinking moment,” he later told listeners on Triple J. “I felt ashamed because I didn’t stand up and do anything because the guy [abuser] kind of had the crazy eyes. And I was [thinking], ‘Get up, say something, tell him to stop.’ And there’s 20 other people on the bus that also did nothing. The guy was getting off [the bus] anyway.” When he did, Stapleton approached the passenger to see if he was OK. “What really broke my heart,” he added, “was he said, ‘Look it’s fine, it happens all the time.’”

There are many factors that determine who will be spectators and who will intervene. Character and life experiences are important, as is professional ability (doctors, nurses and those with first aid training responding to medical emergencies). The number of onlookers can also affect how many will step forward. According to a longstanding social psychological phenomenon known as the bystander effect, the bigger the crowd, the less likely people are to help someone in distress. The presence of many others, it’s thought, actually makes most people feel that they do not have to take responsibility for a situation.

“In many circumstances people don’t act and they look around and they see everybody else not acting and they assume that other people don’t feel the same that they do,” says Sanderson. “I don’t think everyone at every moment should speak up but there are a lot of times where people want to speak up but don’t know how… if you talk about this subject with people, they have so many stories about the time they didn’t say anything – and regrets about it.”

The bystander effect was first documented following the prolonged rape and murder in 1964 of 28-year-old Kitty Genovese outside her New York apartment. The crime was seen or heard by dozens of people who, despite Genovese’s repeated cries for help, all but failed to intervene, according to contemporary media reports. “For more than half an hour 38 respectable, law-abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks,” The New York Times reported a fortnight after the murder. “Twice the sound of their voices and the sudden glow of their bedroom Iights interrupted him and frightened him off. Each time he returned, sought her out and stabbed her again. Not one person telephoned the police during the assault.” One neighbour finally called when Genovese was dead; he told police later that he had only phoned them after much deliberation, saying: “I didn’t want to get involved.”

While the specifics of that report have been questioned over the years, the public furore prompted two social psychologists in 1968 to examine why so many witnesses had not intervened. Through a series of experiments they concluded that the presence of extra bystanders actually diffuses a sense of responsibility.

“It’s tempting to make the easy choice – to look the other way and assume someone else will act,” Sanderson says, adding that in some life-threatening emergencies, when there is far less ambiguity, people tend to be less worried about looking silly if they intervene, even if it means putting their own lives at risk. “Emergency situations do tend to elicit more helping behaviour,” she says.

A paper based on the largest systematic study of real-life bystander intervention published in American Psychologist last year found that in nine out of 10 cases at least one bystander, but typically several, will help – although even in emergencies, Sanderson adds, some are more likely than others to intervene. “People who don’t care what people think about them are much more likely to go in and do something.”

Natalie Dearden could not imagine being a passive witness. “It’s hard for me to bloody bystand,” says the 51-year-old farmer and former butcher from rural Victoria. “I’m always the type to stand up and do something. It’s just in my nature.” Five years ago, on an early spring evening, Dearden was driving to football training near Edenhope, 400km west of Melbourne, when she was among the first on the scene of a serious accident. A car had veered off the highway, across lanes of oncoming traffic, rolled over and smashed into a tree, trapping the female driver who was travelling with her young daughter. By the time Dearden stepped forward the car had overturned on the driver’s side and was belching smoke, threatening to ignite.

In the following minutes she climbed onto the wreck and through a back window, from where she was able to retrieve the little girl. By then another witness had arrived and she hurriedly passed the child to him, ready to race back to the semiconscious driver, whose feet were trapped beneath the pedals, flames already licking the vehicle. Only then did she notice a group of onlookers. “I got the little girl out and I was yelling out for a fire extinguisher and I looked up the road and I saw people taking photos with their phones,” she says now of the four or five bystanders who did not render assistance. Did she express her disdain to them? “I just yelled for a fire extinguisher. I didn’t have time to say, ‘Stop filming’.”

While the onlookers continued capturing vision, a truck driver appeared with a piece of pipe and with his help Dearden was finally able to pull the driver from the car before it exploded in flames. “That woman was going to die if no one came in and helped because I needed more than just me there,” says Dearden, who in one unforgettable encounter witnessed both ends of the spectrum of human responses. There were the upstanders like her. “It took three of us to get her out. And I don’t know how we lifted the car.” And there were those who stood by and filmed. “There could have been three or four more people help with that incident but they valued getting photographs for the paper or their Facebook account or whatever it is over someone’s life.”

“Life is precious and you don’t know what’s going to take it,” Dearden says. “And maybe that’s why some people are bystanders. They know that life is precious and they don’t want to put themselves in that situation and put themselves in jeopardy of losing their life. I can’t tell you about that because that’s not me.”

While Dearden went on to receive one of Australia’s highest bravery awards for her actions that day, it was only later that she stopped to consider how disastrous her choice might have been. “I never thought about my two sons, my father, my husband. I just did it,” she says of the potential personal costs had she been injured in her attempts to help two strangers. “It’s instinct. You see a bloke down, you get off your arse and you’re with him straight away,” she says simply. For many others, however, it’s much more fraught.

The streets of central Darwin are one of the busiest places in the Northern Territory, thrumming with workers and visitors year round, even in the most oppressive days of the wet season when cafes and hostels are still far from deserted. Near one corner in the centre of the city, not far from a hotel and a surf shop and a pretty taverna, a woman lay unconscious for a good chunk of a December afternoon in 2017, ignored by passers-by. As life continued around her, she was repeatedly sexually assaulted.

“In the clear view of anyone who cared to look,” prosecutor Stephen Geary later told the NT Supreme Court, the woman remained on the ground for more than two hours. The 39-year-old had spent the day drinking elsewhere with family before catching a bus into town and passing out across the road from the Throb nightclub about 3.30pm. As she lay on one of Darwin’s busiest streets, another woman stole her skirt. Then Rodney Alimankinni indecently assaulted her for 45 minutes.

Nobody, the prosecutor said, came to the woman’s aid during that time, and Alimankinni was “probably taking advantage” of that fact when he attacked her. “The victim was unconscious in that state for a number of hours in the main street of Darwin,” Geary said, “observable to anyone that walked past, hundreds of cars, numerous people that walked past and momentarily stared, looked at her and moved on.”

Alimankinni pleaded guilty to indecently assaulting the woman and was sentenced to four years and six months in jail. Justice Jenny Blokland said it was “astonishing that no one intervened” but “maybe people didn’t realise exactly what was happening”. She added: “I would like to think anyone who did comprehend what was happening would take some action to protect the victim and to call for police or other help.”

Yet the incident was not unique. “The first time you see a woman sprawled out unconscious on a CBD footpath, it’s a confronting sight. The next time, less so. And when you see it every week or so, it barely rates a mention. Sadly, in Darwin, it’s a common occurrence,” the NT News editorialised in October last year. “And many of us have become desensitised. Maybe we stop briefly and make sure the chest is still rising and falling before we keep moving, getting on with the rest of our day.” The editorial urged locals to help protect women vulnerable to physical and sexual assault.

“This type [of] offending is very prevalent in the Darwin area against unconscious Aboriginal women,” Geary told the territory’s Supreme Court that same month during the trial of another man. He was charged with gross indecency against his cousin, who had also passed out from drinking. “When people see Aboriginal women in this situation where they’re unconscious… they should step in and try to give assistance,” Geary said. “That can be as simple as ringing the police… or standing nearby in some sense of being a protector of that particular victim until the police arrive.”

Standing up may be ideal, but it is not universally instinctive, even in the most horrendous circumstances. “I wish I’d said something,” one man told ABC news in late May after two naked and malnourished teenagers were found locked inside a Brisbane house in squalid conditions. The man said he had visited the home several times and that the teens were “always locked in the room”, a situation that only ended when police were called to the property, not because of the boys’ conditions but because a 49-year-old who lived there had died.

Sanderson calls those who speak up “moral rebels”. They are likely to be extroverts who question authority and, tellingly, tend not to be worried about looking silly – a factor that can unduly weigh upon others’ decisions to help or stand back. “When you tell people that, then all of a sudden the fear of feeling stupid goes away.”

Greg Page keeps thinking back to the day afterhis48th birthday, and the bystanders who kept him alive on the floor of an RSL club. “I was dead. I had no breathing for about 20 minutes. There was no spontaneous pulse.” So what would he have done had he been a witness, instead, that night? “I probably would have just frozen and felt helpless,” he concedes, although he has since learnt that not having a first aid certificate should not preclude you from attempting CPR.

So should he ever be called upon to reciprocate as a bystander, he will make himself respond. As he says: “I call these people my angels. They basically stepped in to save my life. And there are angels out there for everyone. We just need more of them.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout