How an unlikely ally helped deliver the marijuana movement

Since legalisation, pot has remained divisive. Now, major companies are attempting to make it marketable to those who used to fear it.

If you were an art-minded, music-obsessed teenager coming of age in Sydney in the ’90s – as writer David Jacob Kramer was – you spent your weekends hopping from the CBD’s Red Eye Records to Waterfront, Phantom Records, and Half a Cow in Glebe. You were there for the books, racks of CDs, and piles of zines, but you were also eyeing off the other kids in the stores, looking at what band T-shirt they were wearing, recognising faces from the all-ages gigs, quietly hoping you might find your tribe.

It was the zines – hand-made, photocopied publications made by young people and sold for a couple of dollars – that became a way for Kramer to find his tribe. Together with his friend, cartoonist Sammy Harkham, he self-published his own zine. They called it Dick Fry.

“What else are two teenage boys going to name a zine?” Kramer says when I ask why they named it so. “We never knew what we were going to walk away with [from the stores]. It would be so exciting to find a new book or record. Everything was adding immediately to your entire perception of the world and your sense of self. Looking through the zines there was a sense that you could walk away with something that could change your life. And that feeling was intoxicating.”

It’s not hard to trace Kramer’s future trajectory – from publishing zines to running a cult book shop in California and then compiling a socio-historical anthology on the subject of marijuana culture, published late last year.

Kramer is dialling in from his home in Los Angeles, where he lives with his wife Hayley Magnus, an Australian actress who recently appeared alongside Maya Rudolph in the comedy series Loot. Magnus also reviews books on Instagram, attracting a cult following. Her big smile fills the screen as she brings Kramer a coffee, gives me a friendly wave and then sets off for a hike with their glossy black dog, Pip.

When Kramer, who studied journalism in Sydney, moved to LA in 2007, he opened the independent book store Family Books on Fairfax Avenue across the road from the iconic kosher deli Canter’s. The 8km strip, formerly known for its old-world stores catering to the area’s Orthodox Jewish community, had yet to become the epicentre of streetwear and skate-culture that it is today. The book store, which he opened with Harkham and his wife Tahli, became a cult destination for its idiosyncratic selection of books, zines, records, cassette tapes and movies. For the launch of Sheila Heti’s book How Should a Person Be?, Miranda July presented a slideshow of the email correspondence that spawned their friendship. When rap collective Odd Future (with an entourage of 50) did a book signing, the line wrapped around the block. The roll-call of regulars included Spike Jonze, Mike Mills, Thurston Moore, Patton Oswalt and Dave Eggers.

At the same time, Kramer co-founded an advertising agency and worked as creative director on campaigns for Uniqlo, Levi’s, Spotify and Google, often collaborating with the artists and photographers whose books he represented in the store. While the agency, Imprint Projects, has since closed, he continues to work as a freelancer on campaigns for global brands.

After 14 years, Family Books ended not with a bang but a whimper. Like many small businesses the bookstore fell victim to pandemic closures in 2020. “It was sad but also a relief,” Kramer says. “I was stretched thin and excited to do other things.”

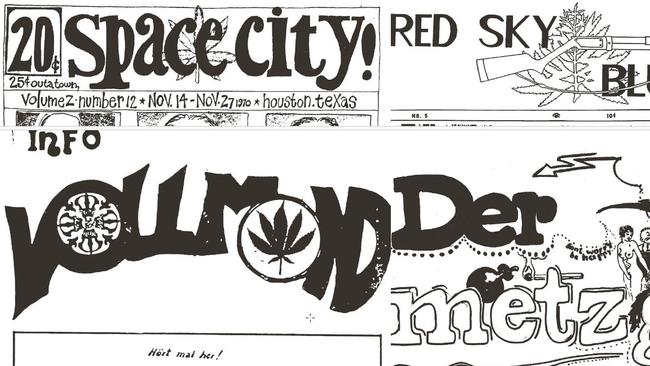

Kramer used lockdown to mine the large number of Underground Press Syndicate (UPS) papers he had stocked in the store. The UPS began as five affiliated newspapers in 1966, and became a network of over 500 publications, reaching millions of readers worldwide. They were filled with articles and illustrations detailing the radical politics, Black Power movement, feminism, sexual revolution, vegetarianism, avant-garde literature and drug-taking that defined the subculture of the 1960s.

“When a writer for an underground paper approves or disapproves of something, he says so,” Joan Didion wrote in her 1968 essay Alicia and the Underground Press. “But to think that these papers are read for ‘facts’ is to misapprehend their appeal. It is the genius of these papers that they talk directly to their readers.”

“The UPS papers were like a proto-zine network,” Kramer says. “Before the internet, there was a physical and cultural isolation to the rest of the world in Australia. Zine culture was about finding a micro niche – if you were into ’80s teen comedies you could indulge in it and build a community around it. The UPS did the same thing with radicalism and linked these communities globally through an exchange of ideas, just like zines did for my generation.”

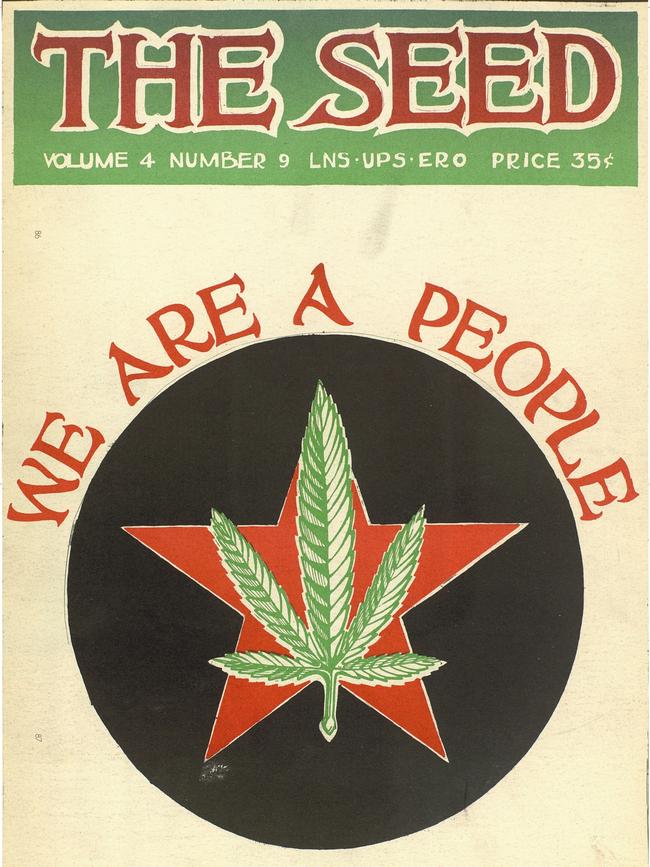

For Kramer, the interest in the UPS became a fixation. He sourced more papers from markets and local bookstores. It was the art within them, specifically the marijuana theme, that most captured him. There were doodles of people smoking joints, vegetables smoking pot, anthropomorphic marijuana leaves, and guides on how to grow the plant accompanied by intricate psychedelic drawings, most by unnamed artists. Kramer saw them as “underappreciated, largely anonymous pieces of folk art”.

There were thousands of papers from all over the world, from US college towns to Helsinki and Mexico City. They were all wildly different. The one thing they all had in common, he noticed, was weed.

The late-night sifting through boxes of UPS papers led to research trips to New York and Germany between pandemic lockdowns, where he met with former distributors and went through their archives. “I spent a week under fluorescent lights in the basement of the Humboldt University of Berlin looking through titles, in a room with no windows.”

Kramer duly wrote a book, Heads Together: Weed and the Underground Press Syndicate, 1965-1973, which was published in late 2023 by Swiss publisher Edition Patrick Frey.

Heads Together also tells the story of how the UPS spawned an unlikely publishing boom, and the marijuana legalisation movement that churned within it. It’s a 500-page anthology featuring hundreds of UPS covers and artworks, from drawings by unnamed artists to Martin Sharp’s famed 1967 Legalise Cannabis poster, created for a rally in London’s Hyde Park. It’s art from a time when smoking pot was an act of rebellion and a signal that you believed in the radical political tenets of the time.

For the book, Kramer took oral histories from key figures from the era, such as John Sinclair, founder of the White Panther Party. Sinclair was sentenced to 10 years in jail for sharing two joints with an FBI agent who had been working undercover on his UPS paper. “They gave him ten for two. What else can the bastards do?” sang John Lennon in his song John Sinclair. He also interviewed writer and poet Ishmael Reed, and First Amendment lawyer and founder of the Free Expression Policy Project, Marjorie Heins.

But within the UPS there was conflict between radical factions who angled for revolution through drugs and rock ’n’ roll, and the journalists and academics trying to achieve change through the printed word. At first, it worked – dry political theories were spiced up by psychedelic imagery, and the revolutionaries were given credibility through association with educated writers. Heins, a former staff writer for the San Francisco Express Times, was one of many voices sceptical of the place of psychedelics in revolution. “Another illusion was this notion that pot and drugs, and to a larger extent the ‘counterculture’ were going to create some revolution: turn on, tune in, drop out,” she says in the book. “I always thought it was ridiculous; if you’re going to drop out you’re not going to accomplish anything.”

It all feels like ancient history today in California where marijuana has been legal for recreational use since 2016. You can get edibles delivered to your door – without need for a prescription of any kind – or sip on a cannabis seltzer. Some marijuana dispensaries, with million-dollar fit-outs, look more like high-end jewellery stores, and their customers are far from barefoot revolutionary hippies. Kramer says it’s normal for pre-rolled joints to be on offer alongside alcohol at parties. “I know so many people who grow weed in their backyard and just give it out to friends. It doesn’t take much to grow enough to last you a year. It is not a precious commodity anymore.”

Growing up in an open-minded household, albeit in a conservative pocket of Sydney’s eastern suburbs, with what he describes as “wholesome hippie parents” (his mother is an artist and his father a lawyer), Kramer says he never had any associations with marijuana being “criminal or insalubrious”. “I would see my parents’ friends smoking weed, and I would see my friends’ parents smoking weed. People that I saw as very responsible adults.” Like many others, he saw Proposition 64, the Californian initiative to legalise cannabis, as both a social justice and criminal justice issue. Before the reforms, posession incurred a hefty fine and felony charges for growing one or more plants were still in place.

Since legalisation, pot has remained divisive – not least because the reforms coincided with the crippling opioids epidemic. Parts of California are in the midst of a catastrophic drug crisis. In San Francisco, where the drug overdose rate is twice what it is in the rest of the country, public drug use is rife. The city recorded its deadliest year for drug overdoses in 2023 with over 800 deaths, according to the San Francisco Chronicle, and it is on track to match the same grim number in 2024.

Kramer is well aware of the problems that have followed legalisation. “Marijuana is still federally illegal in the states so there’s a lack of formal scientific research into the spectrum of benefits, or harms for that matter – especially the new forms available commercially, like the insanely potent waxes, dabs and edibles.”

“A lot of the commercial marijuana companies are trying to make weed alluring to those who have, until now, been scared of it,” Kramer explains. “Their message is that weed provides added productivity, quality of sleep, relaxation, pain relief, energy, romance…” The commercial industry does not necessarily benefit from the tropes associated with hippies. The goals of many of the UPS writers, like Allen Ginsberg and Ed Sanders, was free backyard marijuana, not a weed industry. In many ways, we got both.

Rampant commercialisation has brought its own problems, he adds. Inequality in the booming marijuana business is rife, with many of the “legacy growers” who campaigned for legislation for decades unable to compete with big businesses. “You can’t sell weed legally unless you’re rich here,” Kramer says. “It’s a business – you need a business degree in order to compete in that industry. The costs to compete mean there is still a thriving black market, but that is significantly bigger on the east coast, which didn’t have a super considered commercial weed rollout plan like California did.”

Kramer’s next project for Edition Patrick Frey explores an adjacent movement within the subculture of the ’60s. Alongside photographer Michael Schmelling, Kramer has written a book to be published early next year which documents the homes of hippies who went “back to the land”. Many of these experimental handmade dwellings have been kept hidden for over 50 years to avoid building inspectors.

“Most owner-built homes won’t survive. And one of the reasons I wanted to make the book was to preserve them, at least on paper. When ‘back-to-the-landers’ first moved to these rural areas the local counties wanted to get rid of them, because they were seen as riff raff. Decades later, some are having a similar situation with wealthy people moving out of cities, who see these old eccentrics as undesirables in newly expensive areas.”

Kramer has recently spoken at a tribunal to support one “back-to-the-lander” facing eviction from his handmade home in Marin County where he has lived for the past 70 years. The neighbourhood, just across the Golden Gate Bridge, was once the epicentre of the back-to-the-land movement and is now popular with professionals who commute to San Francisco.

“He invented a new kind of closed-loop toilet system that converts the waste into fertiliser. The accusations logged by the county were that the toilet he had invented was a health hazard with potential runoff for his neighbours.” The hearing was a success, and Kramer’s subject, and his toilet, remain.

A second book on the subculture of the ’60s begs the question: why the interest in hippies? “People like me think there is something wholesome about that generation... But the more you explore it the more you realise it’s not at all what the cliches make it look like. It’s a lot more radical than I knew. How that shaped the generation that shaped me became really compelling.” b

David Kramer and an exhibition of Underground Press Papers will appear at BTWNLNS book store in Sydney on August 28

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout