Clayton’s case: what happens when there is no stroke care

Technological advances in stroke care include remote robotic surgery, clot-busting medicine and new thrombectomy techniques. None was there to stop the damage for Clayton Skewis.

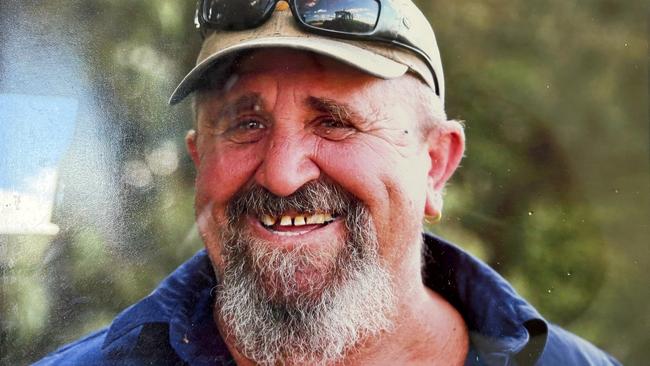

Clayton Skewis was a man whose daily toil on the land contributed in its own small way to the wealth of the nation. A cattle and grain farmer, an alpha male, the salt of the Earth. But when he began to drop things, struggled to focus and then became unintelligible one evening five years ago, the nation did not repay Mr Skewis in kind for his lifetime of hard work. In the immediate aftermath of a massive stroke, the healthcare system catastrophically failed him.

“This is what real-life collateral damage looks like,” says wife Jo, whose struggle to care for her husband who has been left disabled for life in the wake of his stroke has pushed her to the brink of breakdown. “We were let down by a broken system, and there has been no accountability. It’s nothing short of a disgrace.”

Mr Skewis and his wife live in Chinchilla, a rural town in Queensland’s western downs region 300km northwest of Brisbane. If he had lived in a capital city, it’s likely his experience after a massive haemorhaggic stroke would have been very different. Instead, despite paramedics who attended promptly having no doubt Mr Skewis was experiencing a stroke and needed to be flown urgently to a major hospital, he was left to languish in a ward in Chinchilla’s small hospital, which at the time had no CT or MRI scanning machines, for 12 hours. “I sat by his side all night and watched him literally dying in front of me,” Ms Skewis says.

Eventually transferred to hospital in Brisbane via Toowoomba, Mr Skewis was not expected to live. After a craniotomy that drained the massive bleed in his brain, he spent weeks in ICU and then nine months in hospital. He is now paralysed down one side of his body, confined to a wheelchair, and is making slow progress learning to speak again. He requires constant care. The couple have lost all of their life’s savings. “My husband was strong, he was hardworking, he was independent,” Ms Skewis says. “I don’t want any other person to suffer the way we have suffered. I’m ready for decision-makers to hear and to see what real-life collateral damage looks like.”

Mr Skewis’s case is emblematic of the divide that blights Australia’s strong international reputation in stroke care. The latest National Stroke Audit Acute Services Report found an enormous gulf between patients who received access to, and care in, a specialised stroke unit, and those who didn’t, depending on where they lived. While 83 per cent of sufferers living in the cities gained access to a stroke unit, only 61 per cent in inner-regional areas and 35 per cent in outer-regional areas gained such access. There were also large differences across states: only 57 per cent of all patients in Western Australia accessed a stroke care unit; and just 46 per cent in Tasmania; and 41 per cent in the NT. Telemedicine is now providing greater access, but progress is patchy.

“We have pockets of excellence in Australia, but the challenge is to achieve a consistent quality service across all our capital cities, and then outside the cities there are pretty tremendous challenges in access to hyper-acute therapy or advice,” says Kelvin Hill, the national manager of stroke treatment at the Stroke Foundation. “There are tremendous challenges with air ambulance availability and road distances. Some centres have really forged ahead with systems, and others are still sort of developing them. The states are a bit hit and miss as to good statewide systems of care that feed into the specialist centres.”

In 2023, there were an estimated 45,785 stroke events in Australia, which equates to one stroke every 11 minutes. One of the biggest killers and causes of disability in the nation, stroke can happen at any age, but about 80 per cent of events are preventable. Risk factors include high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, high cholesterol and atrial fibrillation or irregular pulse.

Stroke costs the nation $9bn a year, and the lifetime costs associated with strokes that occurred in 2023 exceeded $15bn.

Stroke care has been described internationally as “the most neglected revolution in healthcare”. That catchphrase largely stems from game-changing endovascular surgery for acute ischaemic stroke, thrombectomy, a type of endovascular surgery in which a catheter is inserted into a patient’s blood vessels through either the femoral artery in the thigh or via the wrist. The catheter is fed through the blood vessels to the brain, where the device can deploy a stent to mechanically remove the clot. Despite its remarkable success rates in preventing death and disability, many patients who are candidates for treatment miss out on this surgery, including in Australia, despite this country being a world leader in trialling and proving the efficacy of the technique.

While metropolitan stroke centres achieve a rate of 11 per cent of patients receiving access to thrombectomy nationwide among the estimated 25 per cent with large vessel occlusion who would be eligible, only 4 per cent of regional patients gain access to the procedure. Thrombectomy is not performed at all in the NT, although patients have begun to be transferred to South Australia.

“I think it’s unconscionable that, when we have the technology, when we have the expertise to reverse these strokes, and we have the data that shows you can reduce the disability, that people are missing out on this care,” says Atul Gupta, chief medical officer at the global health technology company Philips. “I think it’s just simple lack of awareness by both patients and payers and governments. If we have all the tools available to prevent such a disabling disease, it’s our responsibility to do it.”

Philips, which manufacturers CT and MRI scanners as well as cath lab and angio suite systems used in image-guided therapy, has joined with the World Stroke Organisation to call for action to expand access to lifesaving stroke care. Stroke is the leading cause of disability worldwide yet is treatable if appropriate care can be accessed in time to prevent widespread brain cell death. When a stroke hits, it attacks up to 1.9 million brain cells per minute. Every minute saved when treating major stroke results in millions of saved brain cells.

The WSO and Philips published a joint policy paper which was accompanied by an editorial in the Lancet Neurology late last year which called for greater access to intravenous thrombolysis (the delivery of clot-busting drugs) and thrombectomy, as well as expanded infrastructures for essential stroke services and an upskilling of the health workforce worldwide. The paper points out that stroke can be prevented, treated and even reversed if treatment is provided rapidly, but huge disparities in access to care persist.

“While effective treatments are available, access to care is limited to just a fraction of stroke patients,” the joint policy paper says. “Technologies such as mechanical thrombectomy are not just another tool but a beacon of hope, offering the potential to improve the lives of millions of people who experience the impact of stroke every year.

“Investing in stroke care and research is not just a financial commitment, but also a highly effective investment. The current human and economic cost of stroke is enourmous today, and without targeted efforts, it will only escalate.”

Although Australia is doing much better than many nations, those disparities are particularly stark across the city-rural divide in this country, despite the window for interventions like thrombectomy expanding markedly in recent years from six hours to now 24.

But technology continues to advance at speed, and one of the bright spots on the horizon for regional and rural patients is the development of robotic endovascular surgery. Within a decade, doctors may be able to treat patients in regional Australia with the same cutting-edge surgery provided to those in big-city hospitals as robots perform mechanical thrombectomy by remote-control. The robotic technology will allow a neurointerventionist in a major city to perform thrombectomy in an angio suite hundreds or even thousands of kilometres away. The patient would be present in the regional centre, and the robot would be controlled by the specialised surgeon in the city.

The Gold Coast University Hospital is the first place in Australia to be trialling the robotic techniques. For the past couple of years, neurointerventionist Dr Hal Rice has been performing robotic endovascular surgery on 10 to 20 patients a year. From a situation in which patients in remote areas take an average of 16 hours to be transferred to a major centre to access thrombectomy, he says patients in these locations in the future will be able to access the lifesaving surgery in less than an hour. “Instead of me standing at the bedside, attached to the bedside is the robotic arm,” Dr Rice says.

There is so much excitement around the new technology, Dr Rice says, that about 20 different start-ups around the world are “feverishly working” on developing robotic machines. “The tech is moving so fast,” he says. “In Australia, geography is the enemy. We currently have improved access to telehealth, but stroke is so time-critical. What this robotic technology means is once this is established, it will mean that these patients having strokes can be treated promptly. It means there will not be significant delays and we will be able to deliver a good outcome rather than patients being left with a lifetime of disability. It is revolutionary.”

But there is much to do to improve stroke care in Australia beyond thrombectomy. As a haemorrhagic stroke patient, Clayton Skewis would not have been a candidate for endovascular surgery, but had he received prompt treatmet in the wake of his stroke, he may have had a different outcome. Instead, he has been left disabled, his wife is devastated, and his care costs the nation hundreds of thousands of dollars each year.

“Chinchilla is not a one-horse town,” says Ms Skewis. “We’re not in the back blocks. At the end of the day, there’s got to be some sort of justice to my life, to Clayton’s life, to be able to speak and say, ‘hey, is anyone going to own this situation?’ Things have to improve in the future.”

Natasha Robinson travelled to Europe to investigate stroke care as a guest of Philips.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout