Is the King Charles’s interest in ayurveda healthy?

After their trip to Australia, Charles and Camilla returned to a wellness resort that’s famous for its ayurvedic treatments. But what is this ancient practice?

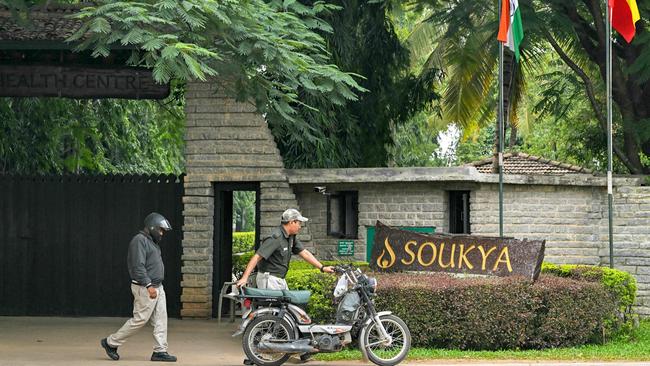

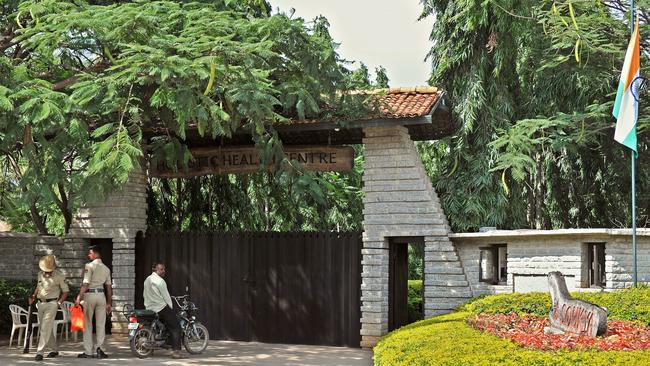

Since King Charles III revealed his cancer diagnosis in February there has been much speculation as to his treatment. He has a well-documented interest in alternative medicine and after his recent foreign trip, during which he and Queen Camilla visited Australia and Samoa, he took an interesting route home. Last week the King and Queen stopped off for a three-day stay at the Soukya international holistic health centre, a wellness resort on the outskirts of the southern Indian city of Bangalore. Soukya offers a wide range of ayurvedic treatments and has long been a royal favourite. The King spent his 71st birthday there in 2019 and Queen Camilla has been with friends several times. According to local media, during his most recent stay the King underwent several ayurvedic rejuvenation, detoxification and immune system-boosting therapies.

Treatments there include panchakarma (eating ghee all day to facilitate a total purge of the gut), shirodhara (having milk from a sacred Vechur cow poured on the forehead) and jal neti (pouring saltwater through one nostril then ejecting it through the other), not to mention other procedures involving mud and magnets. Soukya’s price list alone may necessitate treatment for palpitations (it’s believed to cost £1000 ($1970) a night, without extras, to stay there) and the day-to-day rules are forbidding: no smoking, no alcohol and no non-vegetarian food. Get caught sneaking in a cheeky gin and tonic or a fag under your robe and that’s a £5000 fine. There’s no sex permitted either (it isn’t clear whether this also attracts a penalty), and during downtime no TV and no email, with lights out at 9pm. At Soukya you are supposed to be fostering deep inner peace. Can’t stop thinking about the budget or your brat summer? You’ll need permission to leave. Ayurveda derives from the Sanskrit words ayur (life) and veda (science or knowledge). More than 3000 years old, its central idea is that our health and wellness depend on a balance between prakriti (the body’s constitution) and dosha (life forces), with the onus on prevention rather than cure.

The vata dosha governs movement in the body. The kapha dosha governs structure and lubrication in the body. And the pitta dosha governs digestion and metabolism in the body. If one of the dosha is deemed to be underpowered, increasing intake of certain fruits and vegetables may be recommended, for instance. And surely that’s all for the good? Nothing wrong with donning silk pyjamas and bamboo slippers, then enjoying a bit of yoga, meditation and fresh vegetarian food, as they do at Soukya (the kitchen doesn’t even have a fridge; every meal is freshly prepared one hour before consumption. If it’s hot food, it’s cooked on gas derived from cow dung).

Around the world ayurvedic medicine is enjoying a post-pandemic boom. Its nutritional philosophy pre-dates industrialisation and therefore its focus on a fresh vegetable-based diet long ago anticipated our angst about gut health and ultra-processed foods. Yet there have been many criticisms of the movement. Some have expressed concerns over rasashastra, ayurvedic medicine’s pharmaceutical branch. Treatments involve applying preparations to the body, some of which have been discovered to contain high levels of lead, mercury and arsenic. A 2022 report found that many ayurvedic preparations contain levels of zinc, mercury, arsenic and lead way over World Health Organisation limits. Cancer Research UK warns that some ayurvedic treatments may be toxic or interact with legitimate cancer drugs in a harmful way. Watching the news of the King’s trip to Soukya with interest from the UK is the British-German doctor Edzard Ernst, who was once an alternative medicine practitioner himself. Twenty years ago he was even consulted by the King on how to make complementary and alternative medicines (collectively known as CAM — ayurvedic medicine is considered one) more mainstream. Nowadays he is an arch-sceptic who learnt about the royal visit to Soukya with dismay.

“The King is suffering from cancer so I think he deserves a holiday. But when I hear about the treatments on offer there I have to smile because it is predominantly nonsense,” he says, although he adds: “I’m sure he’s receiving the very best conventional oncology and this visit was simply a well-deserved rest.”

Dr Vijay Murthy is a Harley Street doctor who uses ayurvedic medicine in his practice. He believes it is a valuable complement to so-called allopathic medicine (ie conventional science-based treatment).

“How I see it is the gap that it can fill within our current clinical model is where we see a symptom and we treat the symptom, but we don’t go too deep into understanding why is the body actually manifesting the symptoms, what are the causes,” Murthy says. “And ayurveda gives a framework to understand why in the very first place this process may have taken place in this individual and then try to tweak those aspects which are contributing to the body not being well.”Murthy is a proponent of ayurveda, whereas Ernst has made the journey from believer to sceptic. Born in Germany, Ernst trained as a doctor but also studied homeopathy and acupuncture. He began his career at a homeopathic hospital in Munich but in the early 1090s moved to London and began working in research at St George’s Hospital. It changed his life.

“I became a scientist,” he says. “I tried my best to set aside all biases, including my own. I assessed the efficacy of lots of complementary and alternative medicines via clinical trials, meta-analysis, to draw rigorous conclusions.”

Ernst was appointed the world’s first professor of complementary medicine, at Exeter University. He says he was supposed to train practitioners in the field but instead continued his work subjecting CAM practices to scientific scrutiny with a team of 20 researchers.

This led him to Charles. In 1993 the Prince of Wales, as he was then, started the Prince’s Foundation for Integrated Health, an organisation pushing for CAM practices to gain mainstream acceptance. He and Ernst met twice, at St James’s Palace, then at Highgrove. It was not a meeting of minds. “He said, ‘Oh, that’s you,’ and I said, ‘Yes indeed, that’s me,’” he says, chuckling.

Nonetheless, by 2005 the prince had commissioned the Smallwood report (named after the economist Christopher Smallwood), hoping to show the economic benefits that might follow if CAM practices were integrated into the NHS.

Ernst was asked to collaborate but when he saw an early draft he denounced it as “complete misleading rubbish” and resigned. When parts of the report found their way into this newspaper prior to publication, Charles’s private secretary Sir Michael Peat accused Ernst of a breach of confidentiality. He found himself under investigation by his university.

“They behaved terribly,” he says. “Innocent until proven guilty? No. Instead of defending me, my own university initiated a 13-month investigation. My department collapsed but eventually I was exonerated.” At the time, the Prince’s Foundation for Integrated Health defended the Smallwood report.

Natasha Finlayson, a spokeswoman, said: “We entirely reject the accusation that our online publication Complementary Healthcare: A Guide contains any misleading or inaccurate claims about the benefits of complementary therapies. On the contrary, it treats people as adults and takes a responsible approach by encouraging people to look at reliable sources of information … so that they can make informed decisions. The foundation does not promote complementary therapies.”

The Prince’s Foundation for Integrated Health closed in 2010 after its finance director was jailed for fraud, while Ernst has become one of the world’s most foremost CAM sceptics. He even wrote a book, Charles: The Alternative King, detailing what he views as His Majesty’s misguided medical interests. “I have scientifically researched the whole field for 30 years,” he says, making the point that, in his view, certain CAM treatments are more “dodgy” than others.

Last year he published a book in Germany called Alternativmedizin: Was Hilft, Was Schadet (Alternative Medicine: What Works, What Doesn’t). I see one ayurvedic practice included in the “what works” section, called “oil-pulling”. You put soya oil in your mouth, then suck it between your teeth a bit.

“There is reasonably good evidence that this can prevent gingivitis [inflammation of the gums], although in ayurvedic medicine it is claimed to cleanse the whole body. I tell you now: I really struggled to find an ayurvedic practice to put in the book at all.”

According to proponents of ayurvedic medicine its benefits include: lowering cortisol (and therefore stress), supporting a healthy immune system, boosting cognitive function and improving sleep quality. Fans include Gwyneth Paltrow, Jennifer Aniston and Julia Roberts.

A few studies suggested that ayurvedic preparations could reduce pain and increase function in people with osteoarthritis and help to manage symptoms in people with type 2 diabetes, but most of these trials are small or not well designed, according to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, a US government agency. There is little scientific evidence on ayurveda’s value for other health issues, it adds.

What about the panchakarma detox on offer at Soukya? You spend a day eating ghee, which apparently helps to purge the gut. It sounds awful but, then again, gut health is very much in vogue right now. Shouldn’t we at least acknowledge that it has been part of ayurvedic practice for 3000 years?

“For Christ’s sake, the gut has been a speciality in western medicine for thousands of years too!” Ernst roars. However, he may be fighting a losing battle. Interest in ayurvedic medicine is booming in the west. The demand for wellness holidays featuring its practices is so high that last year the Indian government began issuing the Ayush (AY) visa (an acronym for ayurveda, yoga and naturopathy, unani, siddha and homoeopathy, the six traditional systems of medicine practised in India). And according to a report this year by Market Research Future, the global ayurveda market, worth roughly £7 billion in 2023, will grow to more than £20 billion by 2032.

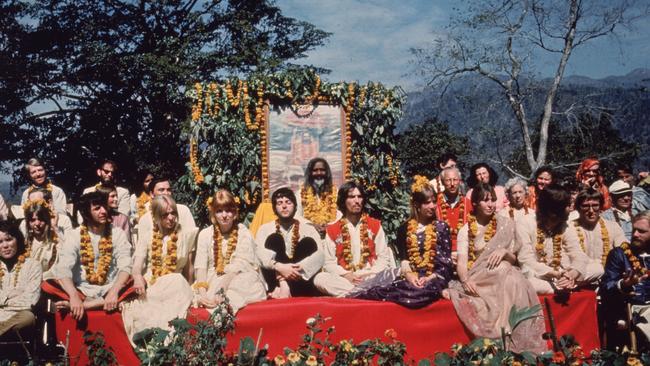

“This doesn’t surprise me,” Ernst says. “I grew up when the Beatles were in the charts and encouraging an interest in Indian culture [the Beatles travelled to India to meet the Maharishi Yogi in 1968; the Maharishi opened the first European ayurvedic centre in Switzerland in 1985]. And why not? It’s a fascinating country. However, the Indian government is now jumping on the bandwagon like crazy.”

Aside from the King and Queen, the actor Emma Thompson and the Dalai Lama have also enjoyed stays at Soukya. Its medical director, Dr Issac Mathai, has been appointed the King’s personal “holistic physician”, travels to the UK to treat him and also plans to open a branch of Soukya at Dumfries House in Scotland (a stately home run for educational purposes by the King’s Foundation).

Ernst is watching it all with scepticism. He insists that in three decades of research, only 5 per cent of all complementary medicines have shown a proven scientific efficacy. However, Murthy claims that, viewed sensibly, ayurvedic practice has much to offer. Remember those doshas, the life forces that need balancing? They might be the route to tailored medicine.

“For a modern world, ayurveda is an adjunct. It is complementary,” he says. “It allows the approach to healthcare for that person to become personalised because in western medicine we cannot personalise healthcare.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout